Women's Voices in the French Revolution

Women, though systematically excluded from formal political power, played a pivotal role in the French revolution

The French Enlightenment set the stage for radical transformation in politics, society, and culture. This blog post explores how eighteenth-century philosophical ideas—especially the concept of human rights—ignited revolutionary fervor in both America and France, how economic hardship and class divisions fanned the flames of dissent, and, notably, how women emerged as a force for change despite being systematically excluded from power.

The Enlightenment

During the eighteenth century, the French Enlightenment introduced a radical rethinking of political legitimacy by arguing that all humans are born free and equal. This period saw intellectuals questioning traditional hierarchies and challenging the divine right of kings. At its core, the movement advanced the idea that human rights were inherent, an idea that later became a cornerstone of revolutionary rhetoric in both America and France.

In America, colonists used the language of liberty and equality to justify their rebellion against a British government that favored an elite few. Although the rebellion was rooted in economic grievances and was led primarily by white landowning men, the adoption of these lofty ideals provided a moral underpinning to the conflict. In France, similar language was wielded against a system that left the majority of the population—particularly the poor—exploited and disenfranchised. The promise of equality and freedom resonated deeply among those suffering under an oppressive feudal system and unjust taxation, igniting a national outcry for change.

Economic Hardships and Social Inequities

By the 1780s, both France and its American counterpart were deeply mired in economic distress. France, heavily in debt from its involvement in both the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, found itself devoting nearly half its budget to servicing national debt. Attempts at reform were continually thwarted by a powerful aristocracy and clergy, who were determined to maintain their traditional tax exemptions and privileges.

The fiscal crisis in France was particularly acute for small landowners, tenant farmers, and peasants. These groups bore the brunt of the tax burden while simultaneously being forced to pay tithes to the church and fees for using communal resources like mills and wine presses. Adding insult to injury, the state-controlled salt monopoly imposed exorbitant prices on a staple commodity, making daily life even more unbearable. The situation was so dire that by 1789, bread alone could consume up to 80 percent of a low-income household’s earnings.

This oppressive economic framework was compounded by social stratification. The aristocracy and high-ranking clergy enjoyed luxuries and privileges, leaving the lower classes to shoulder not only the cost of their own sustenance but also a disproportionate share of the nation’s fiscal burdens. As economic pressures mounted, so did the public’s willingness to challenge an unjust system—a sentiment that would soon crystallize into revolutionary action.

The Double-Edged Sword of Enlightenment Rhetoric

While the rhetoric of the Enlightenment provided a powerful ideological foundation for revolution, it was not without its contradictions. In America, the cry for liberty and equality was primarily championed by white landowners who had little intention of extending these rights to lower classes or women. In France, the situation was more complex: while poor peasants and urban laborers found common cause in their economic suffering, the elite factions of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy manipulated Enlightenment ideals to further their own interests.

Revolutionaries in France—many of whom were middle-class professionals and merchants—found themselves in a paradox. On the one hand, they were inspired by the lofty principles of human rights and popular sovereignty. On the other hand, their struggle was driven by the desire to dismantle an entrenched aristocratic order that had long shielded itself from the burdens of taxation and social responsibility. Thus, the very language of liberty and equality became a double-edged sword, a tool that could both liberate and exclude, unite and divide.

Women at the Crossroads of Revolution

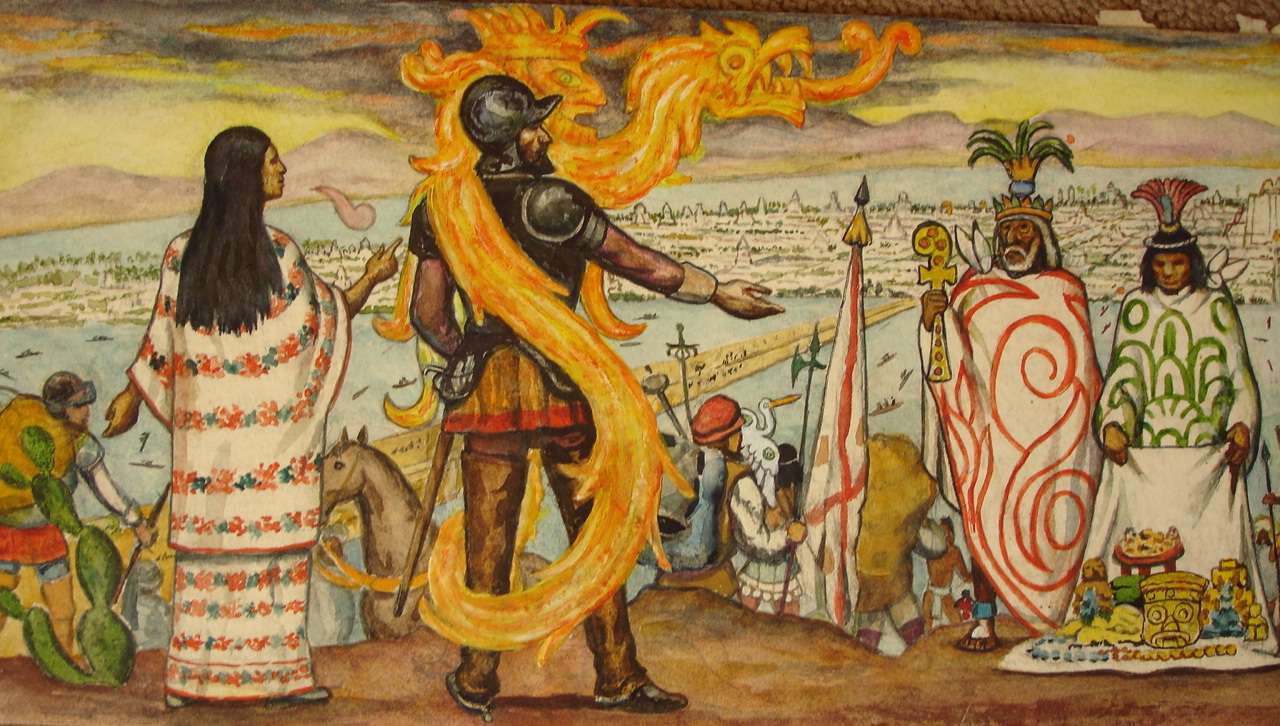

A striking aspect of the French Revolution is the crucial, yet often overlooked, role played by women. Although the Enlightenment and the ensuing revolution were heralded as progressive steps toward universal rights, women were systematically excluded from formal political power. Despite this exclusion, women became active participants in revolutionary events, challenging not only the old regime but also the emerging political order that relegated them to the sidelines.

The Daily Struggles and Unseen Labor of Women

Women, both in rural and urban settings, endured immense hardships under the ancien régime. In the countryside, they worked tirelessly alongside men in the fields, yet their labor was undervalued and underpaid. Urban poor women fared even worse; often relegated to domestic service or menial jobs, they faced long hours, scant wages, and brutal working conditions. The physical toll was severe—many women worked with half the wages of their male counterparts, and life expectancy for women was shockingly short, with many dying before reaching the age of thirty.

These daily struggles were compounded by systemic neglect. While men’s grievances—centered on the fiscal irresponsibility of the elite—dominated public discourse, women’s concerns often went unaddressed. When hardship struck, as during the crop failures of 1785 and 1789 that led to soaring bread prices, it was typically the women of the lower classes who bore the brunt of the crisis. Their labor sustained families in times of severe economic distress, yet their voices were rarely heard in the halls of power.

Women’s Collective Action and Political Mobilization

Despite the prevailing gender biases, women began organizing and expressing their dissatisfaction with the social and economic order. In various local assemblies, women drafted informal lists of grievances—cahiers de doléances—that highlighted their unique struggles. These lists spoke of the daily challenges they faced, from the soaring cost of bread and the tyranny of tax collectors to the lack of police protection and the erosion of traditional guilds that had once provided some measure of security and community.

Urban women, in particular, emerged as a potent revolutionary force. Market women and domestic servants organized protests, marched through city streets, and even took part in violent actions when desperate. Their collective action culminated in dramatic events, such as the women’s march to Versailles, where throngs of armed women demanded that the king address their grievances. This march, though initially successful in forcing the royal family to return to Paris, was emblematic of the broader struggle of women to assert their rights in a male-dominated society.

Intellectual and Activist Voices Among Women

Not all revolutionary women were content with simply protesting; many sought to articulate a broader vision for women’s rights and equality. Figures like Olympe de Gouges emerged as pioneering voices, using pamphlets and declarations to argue that if citizens had the right to bear arms and participate in public life, so too should women. In her seminal work, The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, de Gouges demanded equal access to education, legal rights, and political participation—a radical challenge to the status quo that ultimately led to her execution.

Other influential thinkers, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, added intellectual heft to the argument for gender equality. In works like Vindication of the Rights of Women, Wollstonecraft argued that denying women access to education and political power was not only unjust but also detrimental to the overall progress of society. Despite the revolutionary spirit of the age, however, the political institutions that emerged continued to sideline women. The new constitutional frameworks granted rights to male citizens while deliberately excluding women from the political arena, leaving them to fight on the margins of a male-dominated revolution.

Class Conflict and the Struggle for Power

The French Revolution was not solely an ideological or political struggle; it was also a profound battle over economic resources and class power. Deep-seated class divisions had long plagued French society, and the revolution exacerbated these tensions. The aristocracy and high-ranking clergy, with their entrenched privileges and exemptions from taxation, were pitted against a growing tide of bourgeoisie, peasants, and urban laborers who had borne the weight of fiscal injustice for centuries.

The Burden of Taxation and Economic Exploitation

Under the old regime, taxation was structured in a way that left the majority of the population at a disadvantage. Small farmers, tenant cultivators, and laborers not only had to work hard to produce food and goods but were also burdened with numerous levies, tithes, and fees. The state’s control over essential commodities, such as salt and bread, further aggravated the situation by inflating prices and ensuring that even basic necessities remained out of reach for many.

These economic hardships provided fertile ground for revolutionary ideas. When the price of bread—a staple of the French diet—soared to consume a large percentage of a household’s income, it was a tangible manifestation of the injustices inflicted by the ruling classes. The rising cost of living, coupled with systemic exploitation, galvanized the poor to rise up and demand not only political change but also economic relief.

The Political Reorganization

In an attempt to address the mounting crisis, King Louis XVI convened the Estates General—a representative body divided into three estates (the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners). However, deep-seated grievances quickly surfaced when the Third Estate, representing the commoners, demanded a more equitable distribution of power. Their insistence on doubling their representation was met with resistance from the other two estates, setting the stage for a dramatic reconfiguration of political power.

Frustrated by the slow pace of reform, the representatives of the Third Estate broke away to form the National Assembly, a new legislative body that promised to draft a constitution reflecting the will of the people. This bold move marked a turning point in the revolution. The National Assembly’s agenda was comprehensive, calling for the abolition of feudal privileges, the end of serfdom, and the establishment of a society based on the principles of equality and popular sovereignty.

The Role of Ideology in Mobilizing the Masses

Central to the revolutionary movement was the mobilization of the masses through powerful ideological narratives. The Enlightenment provided the intellectual tools to challenge the existing order, but it was the application of these ideas that truly transformed society. Revolutionary leaders skillfully employed the language of human rights to unite disparate groups—whether wealthy bourgeois or impoverished peasants—under a common banner.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

One of the revolution’s most significant achievements was the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This document was revolutionary not only in its assertion that sovereignty rested with the people but also in its comprehensive articulation of individual rights. It enshrined the principles of liberty, security, and equality before the law, setting forth a vision of a state in which every citizen had the right to participate in governance and to challenge oppressive authority.

However, the declaration was not without its limitations. While it laid the ideological groundwork for modern democracy, it largely reflected the interests and perspectives of male citizens. Women, despite their crucial contributions to the revolutionary struggle, were explicitly excluded from the rights and privileges it enumerated. This glaring omission would spark further debates and protests, as women demanded a place in the new political order.

The Propaganda War

Revolutionary propaganda played a decisive role in shaping public opinion during this tumultuous period. The imagery and rhetoric of the revolution were deliberately crafted to contrast the virtue of the common people with the corruption and decadence of the elite. Iconic figures such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose assertion that "Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains" resonated deeply, became symbols of the struggle for liberation.

Yet, this rhetoric was deeply gendered. The revolutionaries’ concept of virtue was closely tied to masculine ideals of rationality and self-sacrifice, while women were often depicted as embodiments of vice or as inherently unsuited for political life. The vilification of figures like Marie Antoinette was as much about undermining female power as it was about condemning the excesses of monarchy. By equating female influence with moral weakness, the revolutionaries effectively justified the exclusion of women from the political sphere—a legacy that would haunt the struggle for gender equality for generations to come.

Revolutionary Gains and Continuing Struggles

The French Revolution ultimately succeeded in dismantling centuries-old structures of feudal privilege and ushering in a new era of political reorganization. The establishment of institutions based on the principles of popular sovereignty and individual rights laid the groundwork for modern democratic governance. However, many of the revolutionary gains were accompanied by significant setbacks, particularly in the realm of women’s rights.

The Short-Lived Triumph of Revolutionary Women

In the early years of the revolution, women actively engaged in political life. They formed clubs, organized protests, and even took up arms in defense of their communities. Their demands for equal treatment under the law, access to education, and recognition of their political contributions were both bold and unprecedented. Women like Olympe de Gouges and revolutionary groups such as the Society for Revolutionary Republican Women not only challenged the status quo but also redefined the parameters of political engagement.

Yet, as the revolution progressed and power shifted into the hands of increasingly conservative forces, many of these early gains were rolled back. The period of the Terror, marked by extreme violence and political repression, saw women targeted for their participation in public protests and political clubs. In October 1793, the Committee of Public Safety went so far as to ban women from political activities altogether, arguing that their supposed moral frailty rendered them unfit for public decision-making.

The Legacy of Exclusion and the Napoleonic Backlash

Even after the fall of the Terror, the restoration of order under the Girondins and later Napoleon Bonaparte brought with it a return to traditional gender roles. The Napoleonic Code, in particular, institutionalized the subordination of women by stripping them of their status as citizens and relegating them to the domestic sphere. Under this system, women were denied the right to vote, own property independently, or participate in public life, effectively erasing much of the progress made during the revolution.

Nevertheless, the revolutionary period left an indelible mark on the collective consciousness. The very act of mass mobilization and political protest by women during the revolution planted the seeds for future struggles for gender equality. Although the political institutions of post-revolutionary France would continue to exclude women for more than a century, the experience of fighting alongside male revolutionaries instilled a sense of political agency and solidarity that would eventually spur feminist movements in the modern era.

Ideological Divides and the Shaping of Modern Political Discourse

The French Revolution was not just a battle over economic resources or political power; it was also a contest of ideas. The revolutionary discourse, dominated by Enlightenment ideals, sought to redefine the nature of sovereignty and the relationship between the individual and the state. However, the very principles that propelled the revolution also revealed inherent contradictions—most notably, the exclusion of entire segments of the population, particularly women.

Revolutionary leaders proclaimed that sovereignty lay in the hands of the people, yet in practice, political power was reserved for a narrow segment of society. The new constitutional frameworks enshrined rights for male citizens while systematically denying women the same privileges. This contradiction—the celebration of universal human rights alongside the exclusion of half the population—remains one of the most striking legacies of the French Revolution. It highlights how the ideals of liberty and equality can be co-opted to serve narrow interests, and it underscores the ongoing challenge of ensuring that revolutionary gains are truly inclusive.

Despite its flaws, the French Revolution fundamentally altered the way people think about rights, citizenship, and the role of the state. The Enlightenment ideas that underpinned the revolution continue to influence modern political discourse, from debates over human rights to discussions about the nature of democracy and equality. Moreover, the revolution’s impact on women’s history cannot be understated. It was the first time that women, as a collective caste, openly protested against their subjugation and demanded recognition as equal citizens. This legacy would eventually inform later feminist movements, both in France and around the world.

Conclusion

The French Revolution remains a complex and multifaceted event—a crucible in which Enlightenment ideals, economic hardships, and social inequities converged to reshape society. Its legacy is evident not only in the modern nation-state and the institutions that emerged from the chaos but also in the evolution of ideas about human rights and citizenship. The revolutionary rhetoric of liberty and equality, despite its limitations and contradictions, set the stage for a broader understanding of what it means to be a citizen.

Women, though systematically excluded from formal political power, played a pivotal role in this transformation. Their active participation—through protests, intellectual challenges, and even direct political mobilization—laid the groundwork for future struggles for gender equality. While the immediate outcomes of the revolution may have favored a narrow male elite, the seeds of change had been sown. The experience of the French Revolution ultimately taught women that the fight for equal rights was both necessary and possible, even if the road ahead would be long and arduous.