Women’s Emerging Power in Revolutionary America

The post-revolutionary period saw middle-class men gradually consolidating power, while women’s roles became increasingly circumscribed

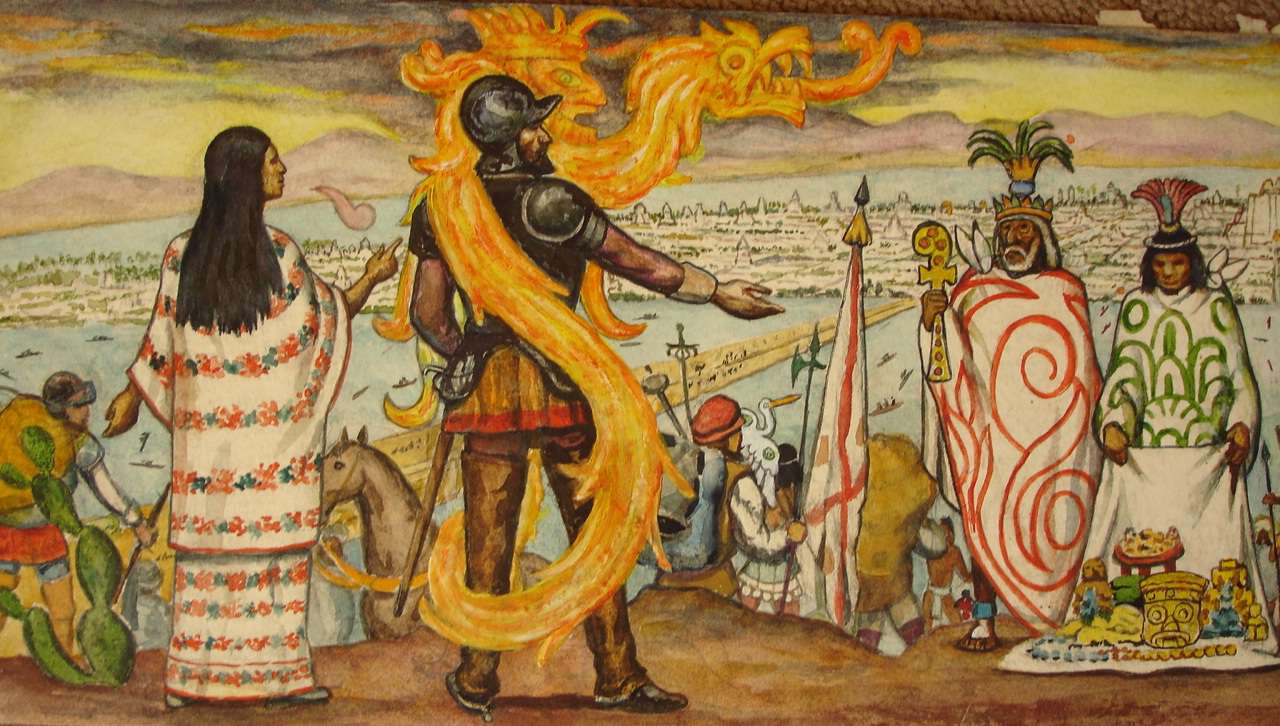

Native American societies, rich in culture and tradition, understood that the arrival of white settlers would forever change their world—even if they could not fully fathom the complete eradication of their way of life. In the early encounters, Native Americans viewed events through the lens of personal and communal immediacy.

Their perspective, much like that of many groups facing rapid change, was centered on daily survival rather than long-range strategy. Even if they had foreseen the profound and lasting devastation that European colonization would wreak on their societies, the overwhelming military technology and relentless drive for domination would likely have made a united and forceful expulsion of the newcomers an insurmountable task.

This tragic lack of foresight is not unique to Native Americans. It mirrors the historical trajectory of women’s rights in early colonial society. Despite being central to the fabric of social life, women found that over time their rights were gradually eroded. Both Native Americans and colonial women faced external forces that undermined their autonomy, yet the systemic challenges they confronted differed greatly. For Native Americans, it was an overwhelming force of Western arms and European expansionism; for women, it was a gradual legal and cultural subordination that redefined their roles within family and society.

The Iroquois Confederacy

While European powers like England and France jostled for nominal control over North America, the Iroquois Confederacy managed to command vast territories across the continent. The Iroquois Council was renowned for its diplomatic skill. With no formal role in European colonial structures, Iroquois diplomats played European factions against one another, extracting gifts and concessions without ever fully committing to any side.

Their strategy of maintaining neutrality in the face of European conflicts was sophisticated. The Iroquois negotiated tirelessly to win the favor of western tribes, even as French Jesuit missions increasingly drew many Iroquois away. At times, they persuaded colonial governments in New York and Pennsylvania to create refuges for tribes shattered by wars in Virginia, Connecticut, Maryland, and Massachusetts. However, the influx of Europeans into Pennsylvania after 1720 eventually overwhelmed the indigenous populations. Despite their diplomatic finesse, the relentless pressure of European expansion and the arrival of even more settlers meant that the Iroquois and other Native American nations faced a relentless loss of land, resources, and ultimately, cultural autonomy.

The Ohio Country and the French and Indian War

The struggle for control over North America intensified in the Ohio Country—a region coveted by both the British and the French. This area, vital for its strategic location at the headwaters of the Ohio River, lay adjacent to French trading posts on the Mississippi. In 1752, British fur traders began penetrating the region, heightening tensions. By 1753, as the French built forts along Ohio’s rivers, colonial leaders like Virginia’s governor sent militias to challenge their construction.

A young George Washington emerged during this period. Leading a militia that attacked the French at Fort Duquesne—a strategic point where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers converge to form the Ohio River—Washington soon found himself trapped at Fort Necessity. In a single day of battle, he lost a third of his men. Although the French allowed the British to retreat, this skirmish marked the beginning of what would become the Seven Years’ War (commonly known in America as the French and Indian War). The war signaled a turning point: Native American dependence on European goods made it nearly impossible to remain neutral, and as the British military recovered, many indigenous groups shifted their alliances toward France.

England’s subsequent victory in the war dramatically reshaped the continent. By 1763, France had ceded nearly all of its North American territories to Britain. Yet the victory was bittersweet for the indigenous populations. Northern tribes, who had once used European rivalries to leverage better outcomes, now found themselves stripped of the ability to use such conflicts to their advantage. The loss of land and traditional ways of life was compounded by British policies that increasingly marginalized Native American interests. The eloquent protests of Mohawk Chief Hendrick in 1753—urging that the sacred Covenant Chain with Albany’s merchants was being broken—capture the profound sense of betrayal felt by many Native Americans during this turbulent period.

A Clash of Empires and Emerging Ideals

The immense debt incurred by Britain during the Seven Years’ War led to a series of revenue-raising measures aimed at the American colonies. Acts like the Sugar Act, the Currency Act, and the Stamp Act were imposed to help repay the royal coffers. These taxes struck a deep chord in colonial society—particularly among property-owning men who had long been accustomed to a degree of local autonomy and self-governance. The British government’s assumption of absolute authority, without considering the established rights of colonists, fueled widespread discontent.

Amid this brewing unrest, a small group of revolutionaries known as the Loyal Nine took decisive action. In August 1765, they protested the Stamp Act by hanging an effigy of Andrew Oliver, the provincial stamp distributor, and by attacking British customs offices. These acts of defiance were just the beginning of a series of protests that would eventually coalesce into an organized resistance movement. The formation of the Sons of Liberty united merchants, lawyers, and working-class men in a network that spanned the colonies. Yet, it was not only men who fueled revolutionary fervor—women, too, emerged as pivotal players in the struggle for independence.

Women’s Revolutionary Role

Even though political power was formally reserved for men, colonial women played crucial roles in the revolutionary movement. Women formed clubs, organized boycotts of British goods, and became key proponents of the Non-Importation Agreements that crippled British commerce in America. The Daughters of Liberty, for instance, emerged as a formidable force. These women not only spun and wove homespun cloth to replace imported textiles but also actively participated in protests by refusing to buy tea and other British imports.

In cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston, women mobilized to support the revolutionary cause. They organized quilting bees that served as both social gatherings and political demonstrations. These gatherings were not only a means to produce homespun fabric but also became venues for the exchange of ideas, propaganda, and the forging of new political identities. Women’s contributions extended beyond economic boycotts; they also provided vital support on the home front by nursing wounded soldiers, cooking for militia units, and even engaging in acts of direct resistance. Stories of heroic women like Molly "Pitcher" in New Jersey—who braved dangerous conditions to bring water to exhausted soldiers—and Sybil Ludington’s long ride to summon militia forces highlight how women were indispensable in sustaining the revolutionary effort.

The British response to colonial dissent was harsh. The imposition of martial law in Boston and the brutal public punishments meted out by British troops underscored the oppressive environment in which colonists—both men and women—sought freedom. While elite men decried British arrogance, many colonists never forgot the indignities they suffered. Propaganda, such as Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the Boston Massacre, would later immortalize these events as symbols of British tyranny and the colonists’ resolve for independence.

Native American and Black Participation

Throughout the revolution, Native Americans and African Americans also played roles that are often overlooked in traditional narratives. Native American tribes, having seen their lands and ways of life eroded over decades of European expansion, largely sided with the British in hopes of preserving their remaining territories. The delicate balance of alliances within the Iroquois Confederacy was shattered as the colonists pressed forward with their demands for independence and land. The repercussions of the revolution were devastating for Native Americans; the new American government largely ignored indigenous rights, and subsequent policies would further marginalize and dispossess them.

Similarly, African Americans found themselves caught in the crossfire. Many slaves saw the revolution as an opportunity for freedom. When the loyalist governor of Virginia offered emancipation for those who abandoned their masters, thousands of slaves attempted to flee. Although most of these runaways were recaptured or succumbed to harsh conditions during transit, the British policy of promising freedom to enslaved people was a significant catalyst for change. Over time, the Continental Army began to enlist African Americans—both free and enslaved—giving them a taste of military service and the promise of eventual liberty. In some instances, these brave individuals, fighting side by side with white patriots, would later serve as a moral and political force in the emerging nation.

The Role of Women in Shaping a New Nation

As the war progressed, the ideas of liberty and self-governance began to permeate every level of colonial society. Revolutionary thinkers such as Thomas Paine and John Adams inspired the colonists to envision a new society—one where the people would govern themselves. Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense, argued powerfully against monarchy and for the establishment of a republic. In response, the Continental Congress declared independence in June 1776, with Thomas Jefferson drafting the Declaration of Independence. This document, with its assertion that “all men are created equal,” laid the philosophical groundwork for the emerging American nation.

However, even as these lofty ideals took root, the revolution revealed deep contradictions—especially regarding the status of women. Women had contributed significantly to the revolutionary cause, yet they were systematically excluded from the political process. Despite being barred from formal political participation, women’s actions during the revolution forced colonial society to confront their roles. In many communities, women not only organized boycotts and supported the war effort, but they also began to articulate their own political identities. The activism of groups like the Daughters of Liberty and the Ladies Associations across the colonies demonstrated that women were not content to remain passive observers.

In Boston, Philadelphia, and beyond, women mobilized public opinion through letters, pamphlets, and newspapers. They criticized British policies and, at times, even challenged the male-dominated leadership of the revolution. Their protests—ranging from burning tea to organizing domestic boycotts—illustrated that the struggle for American independence was not solely a male enterprise. These actions provided the early seeds of what would later evolve into the movement for women’s rights.

The Emergence of New Social and Political Roles

After the revolution, as the United States emerged as a new nation, the promises of liberty and equality began to be applied selectively. The new American republic was founded on principles that celebrated individual rights and self-governance; yet, the rights of Native Americans, African Americans, and women were largely ignored. The founding documents, while revolutionary in their rhetoric, did not extend political rights to these groups. Women, in particular, found that despite their contributions to the war effort, they were excluded from the political process and denied basic rights such as property ownership, the ability to sue or be sued, and even the right to vote.

Abigail Adams, one of the era’s most perceptive political thinkers, famously wrote to her husband John Adams urging him to “Remember the ladies.” Her words captured the frustration of many women who had actively participated in the revolution only to be sidelined in the new political order. Adams and other forward-thinking women, including Mercy Otis Warren and later feminist pioneers like Mary Wollstonecraft, argued that the nation’s commitment to liberty and justice could not be complete while half of its population remained disenfranchised.

These debates laid the groundwork for a slow but enduring transformation in women’s roles. The revolutionary period, with all its turmoil and contradiction, forced American society to re-examine the place of women in both the private and public spheres. Although the new Constitution did not grant women voting rights or citizenship explicitly, the ideological legacy of the revolution—its commitment to the rights of the individual—provided a foundation upon which future generations would build the struggle for gender equality.

The Rise of Feminist Thought and Changing Social Norms

In the decades following the revolution, revolutionary ideals and Enlightenment thinking began to challenge traditional views on gender roles. Women’s participation in political discourse, even if unofficial, inspired a new wave of feminist thought. Influential figures like Mary Wollstonecraft argued that the perceived inferiority of women was not a result of nature but rather of inadequate education and oppressive social conditions. Her seminal work, The Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), is widely regarded as one of the founding texts of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft maintained that women should be educated and treated as rational, independent human beings capable of contributing to society on an equal footing with men.

This new intellectual movement gradually influenced the way middle-class women viewed themselves and their roles in society. As educational opportunities for women began to expand—albeit slowly—new models of femininity emerged. The ideal of the “Republican Mother” took hold: women were seen as the guardians of civic virtue, responsible for raising morally and intellectually capable citizens. While this role was limiting in many ways, it also provided women with a public sphere in which they could exert influence indirectly, by shaping the values and character of the next generation.

At the same time, the post-revolutionary economy was transforming. As manufacturing shifted from homes to factories in the nineteenth century, traditional household production declined. For many women, the home remained the primary sphere of activity—a place of both domestic labor and moral influence. However, the new social order increasingly confined women to roles that emphasized passivity and dependence, while the ideals of republican motherhood attempted to revalorize the domestic sphere as the foundation of national virtue.

The Urban Landscape and the Struggle for Economic Survival

For working-class and poor women, the post-revolutionary period brought challenges that were often starkly different from those experienced by their middle-class counterparts. Urbanization accelerated as cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia expanded rapidly. With the rise of wage labor, many women found themselves forced into low-paying and unstable jobs. While some worked as seamstresses, midwives, or in domestic service, others were compelled to engage in informal economies—selling food on the street or even operating small, unlicensed businesses—to support themselves and their families.

Urban working women faced a harsh reality. The crowded, unsanitary conditions of early American cities led to frequent epidemics and public health crises. Many families lived in cramped conditions with little privacy, and the struggle to secure basic necessities was constant. Despite these hardships, urban women forged communities of support and resilience. They organized charitable societies and mutual aid networks that provided assistance in times of need. In doing so, they laid the groundwork for later social reform movements that would eventually challenge the economic and political inequalities of the new nation.

The economic survival of poor women was intimately linked to the broader social structure of post-revolutionary America—a structure that continued to be dominated by male authority. Widows, in particular, were vulnerable. With few legal rights and limited access to formal employment, many widows found themselves relegated to the margins of society. Public relief efforts, including almshouses and poorhouses, became the only recourse for those who could not support themselves. Yet even within these institutions, the resilience of women shone through, as they worked tirelessly to secure better conditions for themselves and their children.

From the Revolution to the Nineteenth Century

The revolutionary era was marked by a profound contradiction. On one hand, the language of liberty and equality resonated deeply with the ideals of the new nation; on the other hand, these principles were applied selectively. The same society that demanded freedom from British tyranny simultaneously entrenched systems of inequality based on race, gender, and class. For Native Americans, the promise of self-determination was swiftly betrayed as new boundaries were drawn without regard for indigenous claims. For African Americans, the struggle for freedom was marred by the rise of slavery and systemic racism. And for women, the revolutionary rhetoric of equal rights was tempered by legal and cultural restrictions that relegated them to the private sphere.

The post-revolutionary period saw middle-class men gradually consolidating power, while women’s roles became increasingly circumscribed. Legal reforms stripped women of many of the rights they had enjoyed in earlier colonial contexts. Married women, in particular, found themselves with limited control over property and little capacity to engage in business or legal disputes independently. Even as some women—through sheer determination and ingenuity—managed to carve out spaces for economic and intellectual activity, the prevailing social order maintained that true public power belonged exclusively to men.

Yet in the midst of this inequality, the seeds of future change were being sown. The ideas propagated by revolutionary thinkers and early feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft began to circulate more widely, inspiring subsequent generations of women to challenge the status quo. Middle-class women, in particular, started to form reform societies and benevolent associations that would eventually grow into powerful social movements. These organizations not only provided practical support for women in need but also created networks of solidarity that laid the intellectual and emotional groundwork for the later women’s rights movement.

Conclusion

The tumultuous period of Native American decline, colonial conflict, and revolutionary upheaval left a legacy that continues to shape American society today. Native American societies, once formidable and independent, were gradually marginalized by the relentless march of European expansion.

The Iroquois Confederacy’s sophisticated diplomacy and the subsequent collapse of indigenous resistance underscore the tragic consequences of cultural and military imbalance. Meanwhile, the revolutionary struggle for independence—ignited by grievances over taxation and political tyranny—transformed the political landscape of North America, setting the stage for a new nation founded on the ideals of self-governance and liberty.