Women in Early Christianity: From Inclusion to Exclusion

At a time when women were largely marginalized, Jesus's interactions with women defied societal norms

The early centuries of Christianity were marked by radical transformation—a melding of political, religious, and social upheaval in a world dominated by imperial power, competing religious doctrines, and a prevailing patriarchal order.

The Context of Roman Judea and the Seeds of Revolution

During the era of Roman conquest, Judea was a land steeped in conflict. The region, including its colonized and tension-filled capital Jerusalem, was a hotbed for political and religious divisions. Two prominent groups emerged: the Sadducees, a priestly elite aligned with Rome who prized order and stability, and the Pharisees, who opposed foreign domination and clung to hopes of a messianic deliverance. Both factions, though united in their emphasis on salvation through ritual observance, diverged sharply in doctrine. Alongside these groups were the Zealots—militantly determined to overthrow Roman rule—and the ascetic Essenes, who sought mystical atonement through renunciation of worldly desires.

In this charged atmosphere, a charismatic itinerant preacher emerged from Galilee—Jesus of Nazareth. His message, influenced by Essene ideals, resonated with a growing number of followers as he challenged the rigid social and religious hierarchies of his day. Jesus advocated for a radical vision of salvation that transcended traditional barriers of wealth, class, and gender. While rich men monopolized temple rituals by affording expensive sacrifices, Jesus' teachings underscored that salvation was available to all, regardless of social standing.

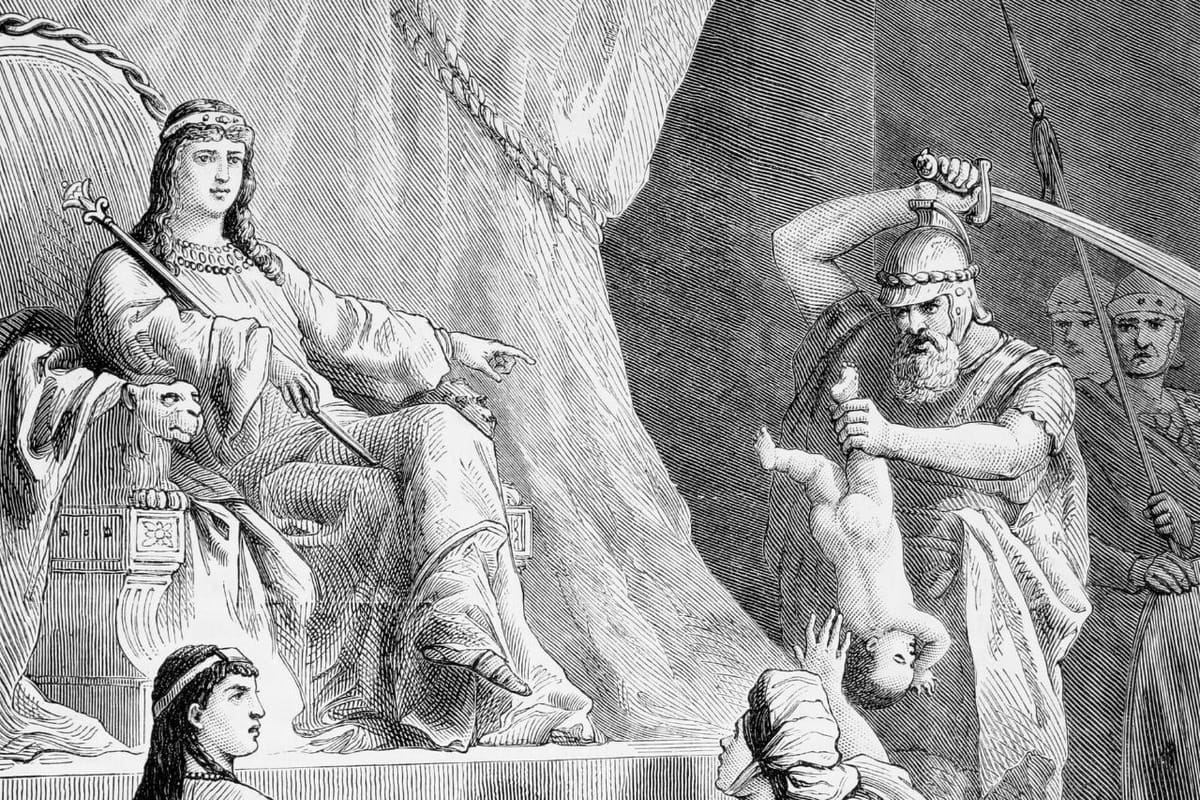

Jesus’ Radical Inclusivity and the Empowerment of Women

Jesus’ ministry was groundbreaking in its inclusive approach. At a time when women were largely marginalized, his interactions with women defied societal norms. He famously engaged with a Samaritan woman at a well—a gesture that astonished his male disciples—and made her the first to learn of his mission. His actions were not isolated; he consistently elevated the status of women. By healing a bleeding woman, defending a woman accused of adultery, and taking Mary of Bethany as a disciple, Jesus demonstrated that spiritual worth was not contingent on gender.

Moreover, Jesus’ teachings questioned the prevailing social hierarchy. His male disciples, many of whom were of lower social standing or even slaves, witnessed firsthand how he broke with tradition by treating women as equals in the quest for salvation. This inclusive ethos extended to his broader message: salvation, resurrection, angels, and the divine realm were accessible to all. Jesus declared that the poor, the enslaved, and the marginalized all had a rightful place in the Kingdom of God. His insistence that every human being, irrespective of gender, could achieve closeness to the divine challenged both the religious authorities of his time and the deeply entrenched social norms.

Women as Pioneers in the Spread of Early Christianity

Following Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, his followers—both male and female—played critical roles in disseminating his message. Despite the chaos of a society under Roman rule, early Christian communities spread across the Middle East and beyond. Women were at the forefront of this expansion. In fact, among the thirty-six founders and correspondents of the early churches, nearly half were women. Rich Roman women not only hosted house churches but also financially supported the burgeoning movement.

Paul, one of early Christianity’s most influential figures, openly acknowledged this inclusivity when he wrote, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” This revolutionary statement, however, did not fully translate into equal representation in the gospel accounts that were later written. Despite the erasure or marginalization of women’s voices in the canonical texts, historical evidence attests to the vibrant role women played as missionaries, preachers, and leaders in the early church.

In communities across Egypt, Syria, Greece, Asia Minor, and Italy, women’s contributions were essential. They not only spread the message of Christ but also provided the organizational backbone for early congregations. Their efforts were not merely spiritual; they engaged in social and charitable works, establishing institutions for the poor, orphans, and widows. Women’s active participation in the early church is a testament to the initial egalitarian spirit that characterized early Christian communities.

The Evolution of Church Structure and the Gradual Marginalization of Women

As Christianity evolved from a loosely organized movement into a structured institution, the dynamics began to shift. The early church, characterized by open intellectual debate and communal decision-making, gave way to a hierarchical organization. Bishops, priests, and deacons gradually assumed authority, and doctrinal debates began to consolidate into what became orthodox teachings. In this process, the revolutionary inclusion of women was systematically curtailed.

Women’s roles began to be redefined and restricted. Despite the early church’s tolerance for female leadership—including women as priests, prophets, and community leaders—male theologians and church authorities increasingly viewed women’s influence as a threat to emerging institutional power. Influential figures such as Irenaeus and later, pseudo-Pauline writings, advocated for the exclusion of women from positions of spiritual authority. Church councils and doctrinal reforms progressively sidelined women, confining them largely to roles such as deaconesses and, eventually, relegating them to the private sphere.

This marginalization was not solely a result of theological shifts; it was also a reflection of broader societal changes. As the church became intertwined with the state and inherited the patriarchal values of Roman society, it increasingly mirrored the gender biases prevalent in secular institutions. Women’s contributions were diminished, their writings suppressed, and their voices silenced. Despite their historical importance, female theologians and mystics found themselves excluded from the dominant narrative of Christianity.

The Monastic Movement and Female Autonomy

Yet, even as institutional power increasingly fell into male hands, women continued to carve out spaces for autonomy within the religious landscape. The monastic movement provided an avenue for women to exercise leadership and scholarly pursuits, albeit within constrained boundaries. In the early centuries of monasticism, double monasteries—communities that housed both monks and nuns—offered a model of religious life where women could hold significant sway.

Abbesses, for instance, wielded considerable authority in these monastic communities. Figures like Hilda of Whitby not only provided spiritual guidance but also played critical roles in shaping local politics and culture. Hilda’s influence extended to training future church leaders and fostering literary talent, as seen in her mentorship of the English poet Caedmon. Similarly, Macrina and Paula established communities that transcended traditional social hierarchies, inviting both wealthy and poor women to live in a spirit of intellectual and spiritual equality.

These monastic institutions became centers of learning, artistic expression, and medical knowledge. The pioneering work of women such as Hildegard of Bingen, who later in life authored influential writings on medicine, natural science, and mystical theology, demonstrates the enduring capacity of women to innovate and lead. Hildegard’s works, which included visionary accounts of a nurturing and feminine divine, not only challenged contemporary medical and scientific thought but also enriched the spiritual tapestry of the medieval church.

However, the increasing institutionalization of the church also meant that the freedoms once enjoyed in these monastic communities began to erode. Over time, external pressures and internal reforms forced many female monastics into stricter confines. By the late thirteenth century, for example, new decrees severely limited the movement of nuns, barring them from leaving convent walls or interacting with the outside world without strict permission. These restrictions underscored the broader trend of diminishing female agency within the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

The Struggle for Intellectual and Spiritual Equality

The tension between early Christian egalitarianism and the later establishment of a male-dominated church is perhaps most evident in the realm of intellectual and spiritual life. Early on, women not only taught and preached but also authored texts that explored profound mystical experiences and theological insights. Women mystics such as Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, and Catherine of Siena left indelible marks on religious literature, offering perspectives that diverged from the dominant interpretations of scripture and doctrine.

Despite these contributions, the growing influence of male scholars and church authorities led to the marginalization of female voices. Over time, many writings by women were lost or systematically excluded from the canon. The process was not merely one of exclusion, but of active suppression, as orthodox theologians decried any doctrine or practice that deviated from established norms. As a result, the rich tapestry of early female mysticism was largely obscured by the subsequent dominance of patriarchal interpretations.

This intellectual marginalization was compounded by the church’s evolving dogma, particularly in its formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity. The Trinity, as defined by early councils, encapsulated a radical theological departure from both Judaic and pagan traditions. However, it also symbolically eliminated the feminine from the divine narrative. By presenting a godhead composed solely of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit—each articulated in exclusively masculine terms—the church reinforced the notion that divinity was inherently male. This theological construction not only justified but also deepened the exclusion of women from positions of spiritual authority.

The Political Implications and the Role of Women in Secular Transformation

The evolving structure of the church had profound political implications, particularly as Christianity became intertwined with the power structures of the Roman and later medieval empires. When Constantine converted to Christianity and later emperors like Justinian adopted church doctrine into state law, the boundaries between secular and religious authority became increasingly blurred. This fusion of church and state further marginalized those who had once been at the forefront of the faith’s dissemination.

In this new order, women’s contributions to the church’s spread and evolution were increasingly erased from official narratives. Yet, outside the corridors of power, women continued to exert influence. Noblewomen and influential laywomen played pivotal roles in converting entire regions through personal correspondence with popes, endowing churches, and founding new religious institutions. Figures such as Queen Bertha, who pressured her husband into converting, and Clothilde, whose influence helped shape the Frankish kingdom’s religious landscape, illustrate that even as institutional structures excluded them, women continued to drive change.

The political consolidation of Christianity also brought about harsher consequences for those who dared to defy its evolving norms. Women who resisted the strictures of the church—for instance, by challenging the exclusion of female prophets or by living independently outside of marriage—often faced severe persecution. Christian emperors and local authorities, seeking to enforce doctrinal conformity, sanctioned the execution or brutal treatment of dissenters. Martyrdom narratives from this period, many of which recount the suffering of female saints like Blandina and Perpetua, underscore the brutal reality of a society determined to silence any challenge to its authority.

The Legacy of Early Christian Women in a Patriarchal Church

The story of early Christian women is one of both triumph and tragedy. In the early centuries, women not only played critical roles in the propagation of the faith but also contributed to its intellectual, spiritual, and cultural richness. Their active participation in establishing and nurturing communities, their groundbreaking theological insights, and their courageous defiance of social norms provided the foundation upon which Christianity was built.

Yet, as the church institutionalized and embraced a rigid patriarchal structure, these early achievements were progressively marginalized. The once-vibrant voices of female mystics, teachers, and leaders were silenced by dogmatic reforms and a male-dominated hierarchy that sought to consolidate power at the expense of inclusivity. This systematic exclusion not only diminished the role of women within the church but also had far-reaching implications for the broader society, influencing everything from property rights to the education of future generations.

Despite these challenges, the legacy of early Christian women endures. Their contributions continue to inspire modern scholars, theologians, and feminists who seek to reclaim and reexamine the historical narrative. The resilience of these women—whether as leaders in early house churches, as abbesses wielding political and spiritual authority, or as mystics whose writings offer alternative visions of the divine—reminds us that the roots of Christianity are intertwined with a spirit of radical inclusivity and reform.

Reflections on the Transformation of Spiritual Life

The evolution of Christianity from a movement marked by radical egalitarianism to one characterized by rigid institutional hierarchies is a complex narrative. It is a story of how religious ideas, political power, and social structures interact to shape the destiny of communities. At its heart, the transformation reveals much about the nature of power and the ways in which institutions evolve to serve dominant interests—often at the expense of those who are marginalized.

For many early Christians, the promise of salvation was a call to a new kind of freedom—one that transcended the limitations of birth, gender, and social class. Yet, as the church aligned itself more closely with the mechanisms of state power, the radical inclusivity that once defined the movement was eroded. In this process, the voices of those who had helped to spread the faith—especially women—were relegated to the margins.

This historical trajectory continues to have relevance today. In modern debates about gender equality, representation, and the role of tradition in shaping cultural norms, the experiences of early Christian women offer both cautionary lessons and sources of inspiration. Their story challenges us to reflect on the ways in which institutions can both empower and oppress, and it reminds us that the struggle for equality is as old as the institutions themselves.