Women in Ancient China: From Prehistory to the Late Imperial Era

Despite the mainstream dominance of Confucian patriarchy, women were never fully passive bystanders.

China is often celebrated for its monumental contributions to philosophy, governance, and culture. Yet behind its grand dynastic narratives lies a complex tapestry of gender dynamics, religious beliefs, and social structures that have continuously evolved over millennia. Archaeological evidence suggests that human life in China stretches back at least half a million years. Over that extraordinary span, Chinese society has transitioned from relatively egalitarian Neolithic cultures to the rise of powerful dynasties ruled by emperors, bureaucrats, and Confucian ideals. Women, once central to mythic cosmologies and social organization, gradually lost status in the face of increasing patriarchy—though not without exerting influence of their own. Below is an exploration of these monumental shifts, drawing on major eras from prehistoric times through the late imperial period.

Early Human Presence and the Seeds of Culture

China’s extensive human history begins with Paleolithic-era remains. Archaeologists have uncovered half-million-year-old skeletons and abundant signs of early culture. By around 6000 BCE, Neolithic communities were already developing sophisticated survival strategies such as slash-and-burn horticulture, animal husbandry, and silk production. Over time, two primary Neolithic traditions emerged: the Yang-shao culture (5000–3000 BCE) in north-central China, and the Lung-shan culture (roughly 4000–3000 BCE) situated in the south and along the east coast.

Yang-shao Beginnings

Yang-shao people lived in small settlements where communal dwellings, shared graves, and food-storage pits suggest some degree of egalitarianism. Archaeological evidence indicates these villagers practiced slash-and-burn agriculture—growing millet, wheat, and possibly other grains—and kept pigs, dogs, sheep, goats, and cattle. Pottery-making flourished, and there are even signs of early silk production.

Notably, the burial customs from this period suggest women may have enjoyed a higher status. Many female graves contain more valuable goods—tools, jade ornaments, pottery—than men’s. One richly furnished woman’s tomb, for instance, included axes, awls, chisels, and various ornaments, hinting that she might have wielded considerable authority. The absence of clear evidence of warfare further underscores the idea that Yang-shao life may have been relatively peaceful, even matrilineal. Some scholars theorize that marriage was matrilocal, meaning husbands moved in with the wife’s family—an arrangement that often confers higher social standing on women.

Lung-shan Developments

Following the Yang-shao period, Lung-shan communities began to flourish in the south and along the east coast. These people cultivated rice, raised chickens and horses, and are known for their elaborate pottery and early forms of divination. Oracle bones—often pig, sheep, or cattle shoulder blades—were heated until they cracked, and the resulting patterns were interpreted by diviners to seek advice on a range of matters. This suggests belief in supernatural forces or ancestors who could provide guidance, already signifying a transition from a more nature-centered cosmology to one that placed ancestral spirits above daily human life.

Unlike Yang-shao culture, Lung-shan villages were often walled, pointing to increased conflict. Excavations show the remains of violent deaths, implying that these communities had become more combative and prone to warfare. Social stratification grew: men’s graves, especially in later stages, held the bulk of burial goods, including tools and signs of wealth. Some graves contained stone phalluses, symbolizing male power. By the time Yang-shao and Lung-shan traditions intersected in northern Honan province, the Bronze Age had arrived, accompanied by entrenched male dominance.

The Shang Dynasty: Statehood, Militarism, and Noblewomen

Out of these formative cultures arose the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), which is widely considered the first true dynasty in Chinese history. The Shang period saw the consolidation of smaller communities under a single ruler—often a local military chieftain—who claimed descent from a supreme deity, Shang Ti. By tracing their lineage to this divine figure, rulers gained the authority to collect tribute, allocate land, and command large armies.

Shang elites received land along with the peasants living on it, creating a nascent form of feudalism. The common people toiled as farmers, craft workers, or conscripted soldiers. Slavery also existed, most often as the fate of war captives. In parallel, a state religion emerged, sanctifying the ruler’s power. Priests, astrologers, and diviners recorded lunar cycles, eclipses, and performed elaborate rituals to ensure prosperity and divine favor. Among these diviners and religious figures were women, though male historians and later Confucian commentators often minimized their roles.

Despite the growing culture of male dominance, some Shang noblewomen achieved significant standing. Oracle bones offer glimpses of their influence; divinations mention women commanding armies or managing lands. The term “Fu” designates elite women—often related to or married into ruling families—and might have originally been written with an ideograph connoting “authority,” though Confucian-era scholars would later reinterpret it to mean “broom” or “wife.”

One particularly intriguing figure is Fu-hao, who features frequently in oracle-bone inscriptions. She not only advised the king but also led troops into battle, amassing armies in the tens of thousands. Archaeologists discovered an intact tomb believed to belong to a woman named Fu-hao. It contained exquisite artworks of jade, bronze, and ivory, along with human and animal sacrificial victims—evidence of her high status. Although the Shang period introduced new modes of subjugation for many women, a few powerful noblewomen still managed to exert genuine authority.

The Zhou Dynasty and the Mandate of Heaven

Around 1046 BCE, the Zhou people to the west overthrew the Shang, proclaiming the “Mandate of Heaven” as justification for their rule. According to this concept, Heaven bestows the right to govern on virtuous rulers; if those rulers become corrupt or inept, they lose that celestial favor. This mandate was a remarkable doctrine in early world history, as it implied some notion of moral accountability in governance.

Under the Zhou, kings granted their relatives and allies near-complete jurisdiction over outlying fiefs. Over time, these regional lords grew powerful enough to challenge the central authority, triggering frequent rebellions and warfare. Although the Zhou initially maintained certain vestiges of older traditions, a pronounced shift toward patriarchy was underway. Traditional worship of ancestors continued, but only men conducted public sacrifices in ancestral halls; women’s role became domestically confined.

It was during the Zhou that the influential yin-yang paradigm gained traction in philosophical circles. Yin represented qualities like softness, darkness, passivity, and femininity, while yang symbolized brightness, assertiveness, and masculinity. Though framed as complementary, yin was often deemed inferior, used as an ideological tool to confine women to household duties and validate male authority in public and political spheres. Over centuries, Confucian scholarship seized on yin-yang thinking to rationalize countless regulations that limited women’s public roles.

Confucian Ideals and the Reshaping of Womanhood

Confucius (551–479 BCE) emphasized moral virtue, hierarchical social relationships, and the importance of education—at least for men. While Confucius did not develop an extensive theory of women’s roles, two of his remarks were later codified as cornerstones of female behavior:

- A woman should “follow thrice”: before marriage, she follows her father’s rank; during marriage, her husband’s; and after widowhood, her son’s.

- Human affairs divide into inner and outer realms: women operate in the household (inner), while men engage in public life (outer).

Marriage, Family, and the State

Over centuries, Confucian interpreters expanded these ideas to cement male dominance in legal codes. Marriages became a means of solidifying family alliances, with daughters married off at young ages. Elite men commonly had multiple wives or concubines, while a widow’s remarriage was condemned in “proper” society. Female virtues centered on chastity, modesty, and obedience. Meanwhile, the notion that only men were fit for education endured—though a few exceptional women, like the Han scholar Ban Zhao, broke barriers by producing significant literary works.

Ban Zhao authored a treatise on women’s education, emphasizing morality and etiquette, and completed her brother’s official history of the Han Dynasty. Though the Confucian establishment admired her scholarship, they upheld her primarily as a model widow—celebrating her lifelong celibacy rather than her intellectual achievements.

From Qin Totalitarianism to Han Confucianism

When the short-lived Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) replaced the Zhou, it briefly imposed a brutal, centralized form of governance. The first Qin emperor, Qin Shi Huang, conscripted countless laborers for massive projects like roads, fortifications (early components of the Great Wall), and his elaborate mausoleum guarded by the now-famous Terracotta Army.

His regime banned alternative ideologies, burning books from Confucian and other schools of thought. After his death, rebels deposed the Qin and established the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). During this era, Confucianism became the official doctrine, heavily influencing legal and social norms, including those that further circumscribed women’s lives.

Women’s Lives Across Dynastic Transitions

China endured repeated periods of fragmentation after the Han, most notably the turbulent Six Dynasties era (220–589 CE). Nomadic rulers, shifting capitals, and foreign religions like Buddhism and evolving forms of Taoism all contributed to a climate of intellectual and spiritual ferment. These eras saw some women gain independence or spiritual authority by joining monastic communities as Buddhist nuns or Taoist adepts.

Yet Buddhism’s scriptures, like those of many patriarchal traditions, also contained passages depicting women as temptations or inferior beings. Over time, Confucian scholars attacked such independent-minded women and belittled Taoist or Buddhist influences that offered women any autonomy. By the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), the pressure to conform to Confucian domestic ideals was growing, especially among the Han Chinese elite.

The Rise of Footbinding

One of the most striking symbols of escalating patriarchy was the practice of footbinding, which became widespread in Song and Yuan (1279–1368 CE) times. Initially a marker of status among the elite, footbinding soon filtered down to many other social groups, except the poorest households that needed women’s full mobility for labor. Girls as young as five or six had their feet wrapped so tightly that bones deformed. The process was excruciating and could lead to lifelong disability or even death by infection.

Despite the immense suffering, mothers bound their daughters’ feet because small, “lily” feet were considered a hallmark of upper-class Han culture. In a highly stratified society, performing the ritual of footbinding enhanced a family’s status and distinguished them from those labeled “barbarians” or lower-class groups who could not afford the practice. Over centuries, footbinding became entrenched, a stark example of women sacrificing physical well-being and freedom of movement for social acceptance and perceived beauty.

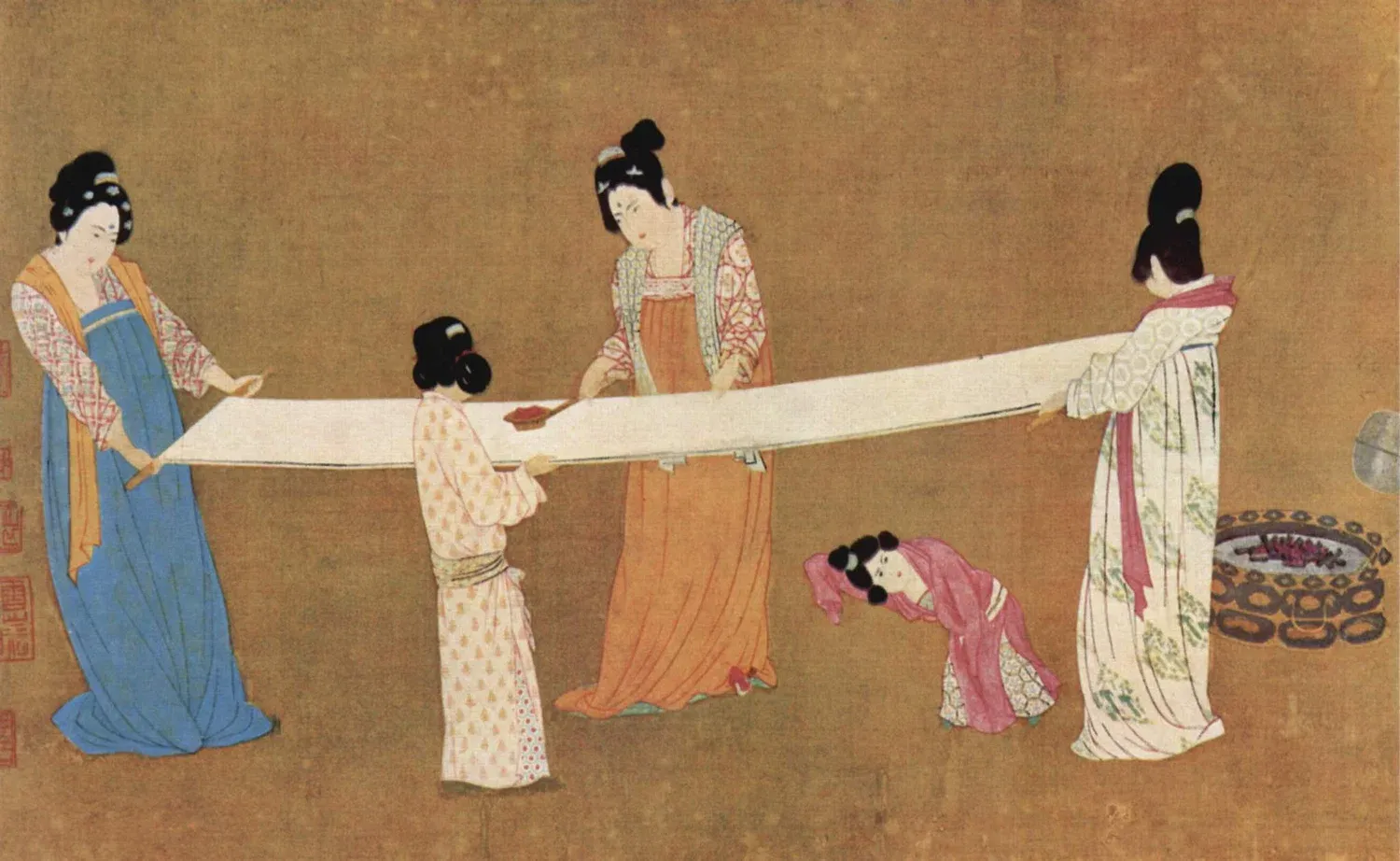

Elite Women, Harems, and Courtesans

During the later imperial era, larger households frequently maintained extensive retinues of women, from wives and concubines to servants, entertainers, and enslaved individuals. In the imperial palace itself, thousands of young women served in the harem. Some were high-ranking consorts who wielded political influence, particularly as regents for child emperors. Others served as entertainers or maids, forming a complex internal hierarchy. Concubinage also offered a path to wealth or influence for women of lower birth: a talented poet or musician could attract the attention of influential men. Some of China’s notable female poets and painters emerged from such harem or courtesan backgrounds, using their artistry to gain visibility.

Still, the overarching ideal was strict female virtue within marriage: early betrothals, rigid fidelity, and unwavering chastity in widowhood. Women with no sons found themselves especially marginalized, as ancestor worship focused exclusively on the male line. A married woman stood outside her birth family and was not accepted fully by her husband’s clan until she bore a son; if she died without one, she was often forgotten. Such customs shaped the desperate priority placed on producing male heirs.

Late Imperial Constraints and Cultural Shifts

By the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, women’s freedoms had narrowed considerably under mainstream Confucian morality. Many young women endured physical confinement in upper-class settings, rarely venturing outside the home. Footbinding, combined with increasingly restrictive norms, often prevented them from working or participating in public life. Female infanticide was more common during times of hardship, as a daughter was seen as a burden—an expense that would ultimately benefit her husband’s family rather than her own.

Yet, as urban centers prospered and merchant classes grew, some women found new opportunities. Certain books on household management and moral instruction started blending practical advice—like how to run a business or manage finances—with discussions of Confucian decorum. Skilled women might run shops or restaurants, earning their families substantial income. Literacy among women rose modestly, leading to increased participation in writing and other cultural arenas. A few became influential authors of popular fiction, painting nuanced portraits of female life behind closed doors.

In parallel, new religious devotions sprang up. One figure that captured the spiritual imagination of many women was Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Originally male in Indian Buddhism, this deity transformed in China into a female form associated with mercy, healing, and the promise of transcending life’s suffering—sometimes symbolically equated with transforming female identity into male as a final step before enlightenment. Her cult signaled a deep yearning to escape restrictive social norms, even if only in a devotional or metaphysical sense.

Conclusion

From the earliest Neolithic societies to the dawn of the twentieth century, Chinese civilization underwent sweeping cultural, political, and religious transformations. Once-matrilineal Neolithic groups gave way to patriarchal dynasties underpinned by Confucian orthodoxy. Militaristic feudal states, divine imperial mandates, the rise of bureaucratic administration, and the interplay of Taoist and Buddhist ideologies each left their mark on Chinese social life—especially on the status of women.

Despite the mainstream dominance of Confucian patriarchy, women were never fully passive bystanders. Elite women like Fu-hao and Ban Zhao leveraged their positions—through marriage alliances, family connections, or scholarship—to exercise power. Others sought refuge in religious communities, becoming Taoist adepts or Buddhist nuns, while still others lived as courtesans or entertainers where they could cultivate artistic talent. Footbinding, once a symbol of class distinction, ultimately became a central target for reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When the Qing Dynasty collapsed and modernizing forces gained momentum, the practice of footbinding—and the patriarchal assumptions supporting it—began to be challenged in earnest.

Over these thousands of years, the pendulum of gender relations in China swung between relative lenience and oppressive constraint. The initial evidence of strong female roles and matrilineal practices in Yang-shao culture underscores that Chinese civilization, far from being monolithic or unchanging, has always evolved in response to political pressures, economic realities, and cultural innovations. Even when Confucian orthodoxy reached its zenith and footbinding soared in popularity, dissident voices—both male and female—advocated for a rethinking of women’s roles.

Learn the statues of women through the history: