Transcendence, Patriarchy, and the Myth of Human Superiority

The belief in human superiority requires a belief in transcendence—a notion that some human beings can rise above their own humanity.

Throughout history, intimations of immortality have been consistently linked with the worship of transcendent deities, almost invariably male, who are considered superior to and in control of earthly events. These deities, and the ideas they embody, have played a central role in the formation of early states and the evolution of patriarchal societies.

The Rise of the Divine Masculine

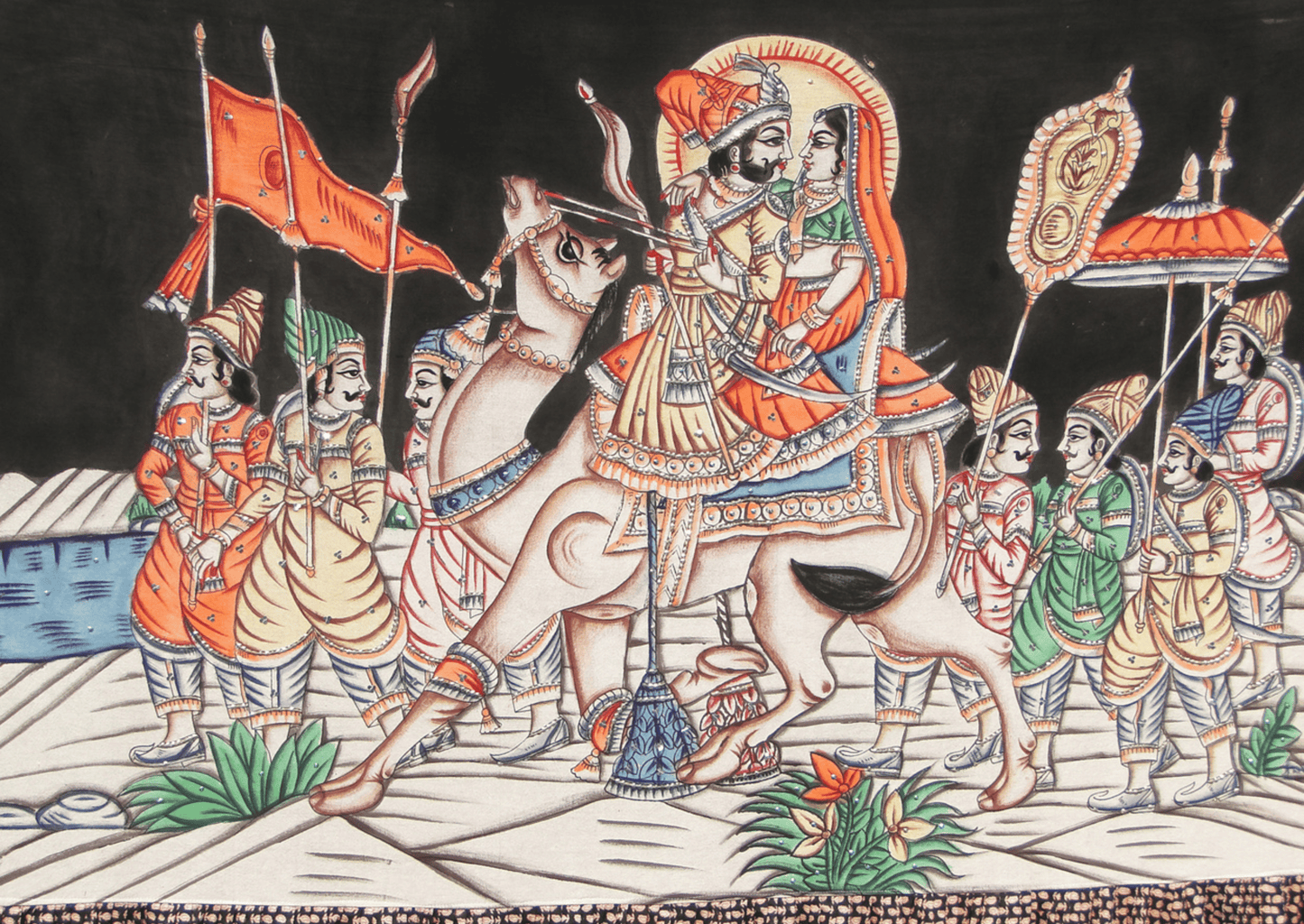

From the earliest days of state formation, human societies have sought to elevate certain individuals—or groups—to a status that transcends ordinary human existence. This belief in transcendence is inseparable from the idea of divine authority. In ancient times, powerful deities were invoked to legitimize the rule of emerging leaders. Unlike the earlier goddesses, who were intimately connected with earthly fertility and the provision of sustenance, the new transcendent gods were depicted as omnipotent, impervious to human failings, and demanding absolute reverence. These gods were invariably male and were seen as the ultimate arbiters of power and control.

The shift from goddess worship to the worship of these transcendent, male deities did not happen overnight. In many early cultures, goddesses once held sway over aspects of life like the fertility of the earth, the success of harvests, and the well-being of women. These goddesses were powerful but not omnipotent—they could bestow blessings such as corn, oil, and fecundity, yet they were also held accountable when things went wrong. As states grew and central authority was consolidated, the cult of the transcendent god began to dominate. These new gods brooked no impiety. They were invoked as the embodiment of an ideal that justified not only the absolute power of rulers but also the belief that some human beings could—and should—rise above the common lot.

The Hebrew Narrative and the Invention of a Nation

Narratives of divine deliverance and eternal superiority are not confined to any single culture. The ancient Hebrews, for example, are often portrayed as a coherent people guided by Yahweh, a supreme deity who established divine order on earth. Yet modern scholarship suggests that there was no single ancient ethnic group called the Hebrews. Instead, biblical texts amalgamate linguistic and cultural influences from various Semitic peoples. Terms and names within these texts reveal layers of language—from proto-Aramaic to early forms of Hebrew—that indicate a melting pot of traditions drawn from across the Near East.

One influential theory, advanced by scholar George Mendenhall, traces the origins of the Hebrews to a series of migrations during the early Bronze Age. Around 2300–2000 BCE, the clannish Amorites migrated from northeast Syria. Some of these groups eventually found themselves in Egypt, and, generations later, a small band of Semitic slave captives would escape from Egypt. Led by a family—Moses, Miriam, and Aaron—they united disparate groups under the banner of a single, all-powerful deity: Yahweh. According to the biblical account, these émigrés achieved the near-miraculous feat of overthrowing the governments of two fertile regions in Transjordan and settling in Palestine.

Mendenhall argues that the story of the Hebrews is less an account of a preordained, divinely guided people and more a tale of radical rejection of established political authority and traditional religion. Dissatisfied with the oppressive, tax-driven governance of Canaan—a province once under Egyptian rule—the Hebrews, known also as the “Habiru,” banded together in a deliberate act of defiance. In their migration into the desert, they embraced a new social order based on the idea that power ultimately belongs only to God. By uniting these groups under Yahweh, Moses is said to have invented a new deity capable of fusing strangers into a cohesive nation.

Tribal Religions and Universal Faith

Before the emergence of a singular, transcendent god, various tribal groups worshipped an array of household deities. Each clan had its own gods and goddesses, with local rituals and customs that reinforced kinship bonds. For a disparate collection of peoples to unite into a nation capable of defending itself, these tribal divisions had to be overcome. According to Mendenhall, Moses transformed the religious landscape by elevating Yahweh to a universal god—a deity whose authority would bind the various clans into the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The unifying power of this new faith is evident in the lasting rituals and narratives that have shaped Jewish identity for millennia. The Passover, for instance, is a ritual celebration of the Exodus—the dramatic escape from Egyptian bondage—which remains central to Jewish education and identity. In creating a unified set of laws and a covenant that placed divine authority above earthly kings, the Hebrews forged a collective identity that rejected the oppressive, stratified societies they had left behind. They insisted that power should belong not to a select few but only to God, thereby challenging the traditional, patriarchal modes of state formation.

Matricentric Roots and the Transformation to Patriarchy

Although the biblical narratives are often dominated by patriarchal themes, evidence from earlier times suggests that many ancient Near Eastern societies had more balanced, even matricentric, social structures. Some scholars argue that before the rise of strictly patriarchal systems, the people of Israel may have been organized around matriarchal principles. Biblical texts hint at these earlier arrangements—for instance, by referencing women as central figures in the transmission of lineage and blessings.

The etymology of key Hebrew words further supports this idea. Terms for kin-group, clan, or tribe often trace back to words associated with the womb, indicating that descent was once understood in maternal terms. Over time, however, these practices were reshaped. As the society adopted a new model centered on the transcendent, male Yahweh, the matriarchal elements began to fade. This transformation is evident in the biblical emphasis on the patriarchal order where male figures such as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob come to represent the foundational leaders of the nation. Yet, even as patriarchal norms were codified, remnants of earlier, more egalitarian practices persisted—often in subtle and contested ways.

Early biblical narratives offer glimpses of this earlier balance. Figures like Miriam, Deborah, and even Rahab demonstrate that women once played vital roles in leadership and decision-making. Deborah, for example, is depicted not only as a prophetess but also as a judge and military leader who mediated disputes and led armies. These examples, however, gradually give way to a more rigid patriarchal narrative in later texts, where women become increasingly defined by their sexual and reproductive roles rather than by their contributions to governance or spirituality.

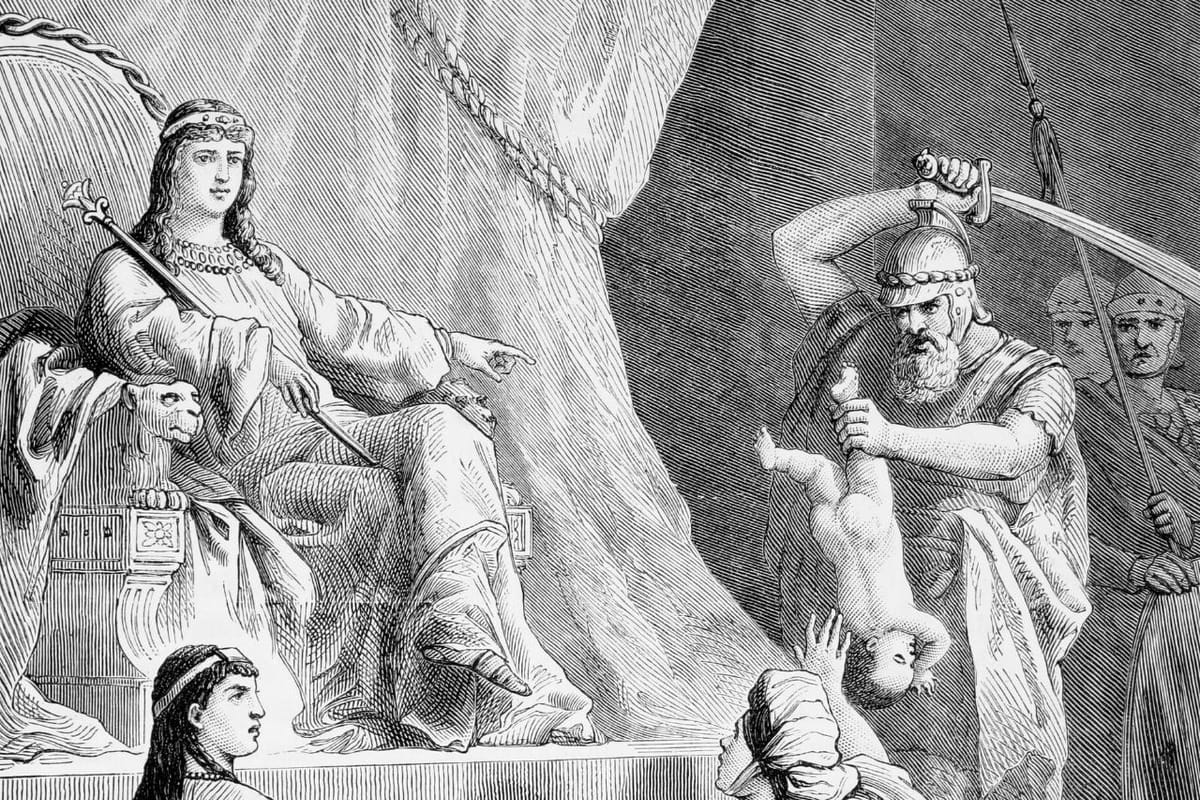

The Legal Codification of Patriarchal Values

One of the most enduring legacies of state formation in the ancient Near East is the legal codification of gender inequality. Early laws were not designed solely to maintain order; they were instrumental in constructing a social hierarchy that systematically subordinated women. The laws of Uruk in Sumer, for instance, are among the first recorded legal codes that explicitly target women—criminalizing female adultery while leaving similar actions by men largely unpunished. This legal double standard was a clear reflection of the emerging patriarchal mindset.

As societies grew more complex and states became more centralized, these laws evolved to restrict every facet of women’s lives. Women were denied the right to own property, to engage in business, or to participate in public decision-making. Their contributions to society, although essential, were devalued, and their roles were strictly confined to the domestic sphere. Such legal restrictions were not unique to one culture; they appeared across various early states in Egypt, Babylonia, Athens, and later, in China and among the Hebrews.

Religious texts further reinforced these legal codes. The central chapters of Leviticus, for example, provide detailed regulations regarding women’s bodies and their supposed impurity. These texts equate natural processes such as menstruation and childbirth with pollution, subjecting women to prolonged periods of isolation and ritual cleansing. By codifying these practices, the religious authorities effectively relegated women to the margins of both public and sacred life, establishing a lasting framework for gender inequality.

The Social and Economic Impact of Patriarchal Laws

The implications of these patriarchal laws extended far beyond the legal realm—they reshaped the very fabric of society. When the family is the primary unit of production, especially in a context where men are often absent due to warfare or labor migration, women’s roles become both vital and undervalued. In many ancient societies, women managed the home as a production center—processing food, weaving textiles, and caring for children—yet they were often denied any economic or legal autonomy.

The proverbial “good wife” described in Proverbs 31 is an archetype that both celebrates and confines women to the domestic sphere. She is praised for her industriousness and ingenuity, yet her achievements are measured solely in terms of her support for her husband’s status and the household’s economic well-being. Such narratives, while seemingly honoring women’s contributions, ultimately serve to reinforce the subordinate position of women in a patriarchal society.

Furthermore, the economic subjugation of women was intertwined with the regulation of their sexuality. In many cultures, a woman’s reproductive capacity was seen as the ultimate asset—and the primary means by which a man could exert control over her. Laws prohibiting abortion or the use of birth control were not merely about controlling population growth; they were about ensuring that women remained tethered to their roles as childbearers and caretakers, unable to claim any independent authority over their own bodies.

Propaganda, Myth, and the Reinforcement of Male Dominance

Central to the maintenance of patriarchal power is the role of propaganda and myth-making. Early state rulers relied on grand narratives that celebrated divine authority and the inevitability of male superiority. Ceremonies, religious texts, and public rituals all served to reinforce the idea that power was not only a privilege but also a sacred trust granted by transcendent forces.

These myths were carefully crafted to create a sense of continuity and inevitability. The belief that certain individuals are inherently superior—and therefore destined to rule—has been a potent tool in the hands of political elites. By claiming divine sanction, rulers could justify not only their authority but also the systemic subjugation of those deemed “inferior,” particularly women. This ideological framework was so deeply ingrained that even in later periods, when more democratic forms of governance emerged, the underlying logic of male dominance persisted, often hidden beneath the veneer of equality and fairness.

Educational institutions, religious organizations, and even family structures contributed to the perpetuation of these myths. From childhood, individuals were taught that the social order was natural and divinely ordained. This process of social conditioning ensured that the patriarchal system was not easily questioned, even as its inherent contradictions became apparent. In modern times, while overt expressions of these ideas may have diminished, the cultural legacy of these myths continues to influence our understanding of gender, power, and leadership.

Challenging and Redefining Patriarchal Norms

Despite the enduring legacy of patriarchal thought, there have been significant challenges to these ideas throughout history. Social and political movements—from the feminist movements of the twentieth century to ongoing struggles for gender equality today—have sought to dismantle the myths that justify male dominance. By questioning the supposed naturalness of male superiority and advocating for the rights of all individuals, these movements are gradually reshaping cultural narratives.

Historical reinterpretations have also played a critical role in this process. Scholars now recognize that many of the narratives once taken for granted—such as the idea of a homogenous, divinely chosen people or the inevitability of male leadership—are, in fact, constructions that served particular political and economic interests. By deconstructing these myths, modern historians and activists are working to build a more inclusive understanding of the past—one that acknowledges the contributions of women and challenges the hierarchical structures that have long defined our societies.

Religious reform has been another powerful avenue for change. In many cases, new interpretations of sacred texts have opened up space for a more egalitarian understanding of divine authority. While the ancient texts of Leviticus and other canonical works once enshrined the subjugation of women, contemporary interpretations increasingly emphasize themes of compassion, equality, and shared responsibility. This ongoing evolution in religious thought reflects a broader cultural shift—a recognition that the old myths of transcendence and male superiority no longer serve the needs of a just and inclusive society.

The Enduring Lessons of Ancient Myths

As we examine the historical evolution of the belief in human superiority and the associated myth of transcendence, several enduring lessons emerge. First, the transformation from goddess worship to the worship of transcendent, male deities was not simply a religious shift—it was a foundational change that restructured entire societies. This shift provided the ideological groundwork for the emergence of centralized states and the consolidation of power in the hands of a few. In doing so, it also set in motion a long history of gender inequality that has had lasting effects on social, economic, and political life.

Second, the legal and social codifications of patriarchal values were not accidental. They were deliberate strategies designed to control women’s bodies, labor, and sexuality. By understanding how these laws were crafted—and the purposes they served—we can better appreciate the challenges faced by those who seek to dismantle these systems in the modern world.

Finally, the myths and narratives that once justified male superiority continue to exert influence today, even as societies have made significant strides toward gender equality. Recognizing the historical roots of these ideas is a crucial step in challenging them. It allows us to envision alternative models of leadership and social organization—models in which power is not a divine entitlement but a shared responsibility, and where every individual, regardless of gender, is valued for their inherent humanity.

Reimagining a Future Beyond Patriarchy

The path toward a more egalitarian society is complex and challenging. However, by drawing lessons from the past, we can begin to imagine a future where state power is not built on myths of transcendence and superiority but on principles of equality, shared responsibility, and mutual respect. This reimagined future requires a fundamental shift in how we think about power and leadership.

Educational reform is a critical part of this process. By teaching critical thinking and promoting a more inclusive view of history, we can help future generations recognize that the old myths of male dominance are not inevitable but are, in fact, constructs that can be challenged and changed. Political and economic reforms that ensure equal access to opportunities and resources for all individuals are equally essential. When women and marginalized groups have the means to contribute fully to society, the rigid hierarchies of the past begin to erode.

Religious institutions, too, have a role to play in this transformation. As modern interpretations of sacred texts evolve, they can offer a more inclusive vision of divine authority—one that emphasizes compassion, equality, and the inherent dignity of every human being. This vision can help to undermine the long-held belief that power is the exclusive domain of a select few, instead fostering a more collaborative and humane society.

Conclusion

The belief in human superiority and the myth of transcendence have been central to the formation of states and the establishment of patriarchal societies throughout history. From the early days of goddess worship to the rise of transcendent, male deities, these ideas have provided the ideological foundation for systems of governance that prioritize power, control, and inequality over justice and equality. The Hebrew narrative, with its complex origins and transformation under the leadership of figures like Moses, illustrates both the power of myth and the potential for these myths to be reinterpreted over time.

The legal, social, and economic codifications of patriarchal values have shaped the lives of countless individuals, limiting the rights and opportunities available to women and reinforcing hierarchies that persist even in modern democracies. Yet the historical record also reveals moments of resistance and transformation—instances in which powerful women led communities, in which tribal religions were reshaped into universal faiths, and in which new interpretations of sacred texts offered hope for a more egalitarian future.

Keep reading: