Tracing the Roots of Patriarchy in Early India

In some ways, the repeated tension between revering female divinity and subjugating actual women speaks to a broader paradox in Indian culture.

Human history in the Indian subcontinent stretches back thousands of years, revealing cultures both dynamic and deeply complex. Early settlements along the Indus River cultivated vibrant city life in places such as Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, while a succession of religious and philosophical traditions later reshaped social hierarchies and gender roles. Over time, patriarchal norms gathered momentum, particularly under Brahminical authority. Yet, even in times of intensifying constraints, alternative paths—through Buddhism, Jainism, bhakti spirituality, and other movements—offered women some scope for spiritual or social freedom. This post traces the multifaceted development of gender dynamics in India, from the ancient Indus civilizations through the formative Vedic period, and finally into the era of the Laws of Manu and classical Hinduism.

The Indus Valley Civilizations

By around 2500 BCE, the Indus Valley—encompassing sites like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro—was home to large, well-planned cities with extensive trade networks and advanced agricultural practices. Although much about their social structures remains unknown, some clues suggest local councils and central cities collaborated or shared governance. Certain oral traditions, written down only much later, depict a society in which clan councils ruled villages and possibly reported to urban centers.

Archaeologists and historians rely heavily on material remains and later textual references to piece together Indus Valley gender relations. One ancient marriage hymn, though likely compiled or interpreted by later priestly authors, imagines a bride speaking confidently in public assemblies in her old age—implying that younger women had limited public roles. Over time, as patriarchal norms tightened, Indian women would be barred from all such assemblies. Historian Veena Oldenburg argues that both gender and age hierarchies probably existed even in these ancient days, reflecting broader patterns of male dominance.

The earliest societies in the subcontinent likely included diverse arrangements: some matrilineal, some patrilineal. Ultimately, major shifts would occur with the arrival of a new group that viewed itself as racially and culturally distinct: the Aryans.

Aryan Arrivals and the Early Vedic Period

After about 1700 BCE, Indo-European–speaking peoples referred to as “Aryans” (“the noble ones”) began moving into northern India. Their expansion was part of a wider phenomenon: similarly Indo-European groups invaded regions like Greece, Crete, and Iran. The Aryans who came into India were patrilineal and patrilocal, worshiped predominantly male gods, and possessed a clear sense of stratification. Yet they were not entirely male-dominant: the term vispatni denotes “female head of a clan,” indicating women sometimes held recognized authority.

Early Vedic Culture and Cattle-Based Economy

From around 1200 to 900 BCE—the Early Vedic period—these herding communities raised sheep, goats, and cattle, with crops such as barley and vegetables also in cultivation. While men often performed major sacrificial rituals and participated in assemblies, women’s labor, especially tending and milking cattle, was crucial. In fact, the Sanskrit word for daughter, duhitr, derives from the verb duh, “to milk.”

Despite their contributions, women lacked direct control over wealth. Cattle raids, distribution of stolen or gifted animals, and the right to preside over sacrifices remained tied to men. Elite men or “chiefs” (rajanyas) performed the most significant rituals, reinforcing their higher status. Yet a few female names appear in Vedic hymns—like Vispala, who fought in battle and received a new iron leg from divine healers. Their very presence in these texts suggests that while patriarchy was growing, certain women still carved out roles of influence or strength.

Vedic Religion and Early Female Presence

Vedic religion revolved around sacrificial rites, often involving animals, grains, or the intoxicating (possibly psychedelic) drink called soma. Though major deities such as Indra (storm god) and Agni (fire god) were male, the RgVeda—the oldest of the four Vedas—references female deities too. Some scholars see these nods to goddesses as vestiges of earlier matrilineal or goddess-centric traditions that persisted within a patrilineal Aryan framework.

Nevertheless, the principal composers of the RgVeda were male priests, whose focus was on regulating and controlling women’s lives. The text praises the birth of sons, largely ignores daughters, and includes passages describing men’s concerns about “undisciplined” women. Still, a handful of verses or entire hymns are credited to female seers. These voices, however faint, provide critical insight into women’s earlier agency before more formal patriarchal norms solidified.

Evolving Social Structures and Gender Norms

Over time, as the Vedic period advanced (roughly 1000–600 BCE), societies expanded and stratification deepened. Archaeological findings indicate the spread of agriculture, iron tools, and settled life. Large numbers of smaller villages coalesced into more centralized regions governed by emerging monarchies. Power hierarchies became institutionalized, and the caste system (varna) started taking shape.

The Origins of Caste

The word “caste” (from Portuguese casta) translates the Sanskrit varna, meaning “color.” Aryans—often described as fair-skinned—separated themselves from the darker-skinned peoples they encountered. Over time, varna came to denote four major categories:

- Brahmins: Priests and teachers (the highest varna).

- Kshatriyas: Warriors and rulers.

- Vaisyas: Merchants and skilled tradespeople.

- Sudras: Artisans, farmers, and laborers (often locals subjugated by the Aryans).

Some were outside even the Sudra category, forced into menial tasks deemed “polluting”—like handling waste or cremation—which gave rise to “untouchables.” As economic, ritual, and social distinctions hardened, so too did patriarchal ideals. Influential religious texts of the time began restricting women’s roles in public sacrifice and property ownership.

The Decline of Female Ritual Power

Earlier accounts recall women making substantial offerings, but as male priests sought to monopolize spiritual authority, female donors and officiants were sidelined. By the late Vedic period, new large-scale sacrifices such as the ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) further diminished women’s autonomy. The ashvamedha ritual involved the king’s wife symbolically copulating with a sacrificed horse to ensure fertility of the realm. In essence, it became a display of political power, overshadowing any real female agency.

Simultaneously, genealogical lineage—and salvation—were defined more rigidly through the male line. Ancestor worship hinged on having a son capable of carrying out specific rites. Women were grouped alongside Sudras as less pure, deemed ineligible for high religious functions. This growing patriarchy did not eliminate local goddesses or matrilineal customs entirely; India’s vastness meant different regions clung to older practices. Still, the drift toward limiting women’s public religious roles was unmistakable.

The Rise of Buddhism, Jainism, and New Paths for Women

Around 600 BCE, the Indian subcontinent underwent a wave of political, economic, and religious upheaval. Trade flourished, city-states emerged, and ambitious rajas fought relentlessly for power. Traditional clan-based structures eroded. Out of this climate of strife and disillusionment, new religious or philosophical movements arose: most notably Buddhism (founded by Gautama, the Buddha) and Jainism (founded by Mahavira). Both stressed transcending worldly attachments and questioned the established Vedic order.

Alternative Visions of Salvation

While the final segments of the Vedas—the Upanishads—also turned toward spiritual introspection, emphasizing the concept of karma and rebirth, their path to salvation (moksha) largely favored high-caste men. By contrast, Gautama and Mahavira taught that ethical living and proper practice could release anyone from the cycle of rebirth, regardless of caste or gender. They opposed many cruelties, especially ritual animal sacrifices that had grown so prominent in Brahmin orthodoxy.

Yet, even as the Buddha preached equality in salvation, he was initially reluctant to allow women to join his monastic order. He feared their presence would erode discipline. Pressed by his foster mother, Maha Prajapati Gotami, he relented, stipulating that nuns would occupy a lower rung than monks. Despite this second-class status within monastic structures, Buddhism’s promise of enlightenment for all was revolutionary. Women quickly joined the nunneries, seeing in them a rare escape from forced marriage, domestic labor, and sexual vulnerability.

Women’s Voices in Early Buddhist Texts

The Therigatha (“Psalms of the Sisters”) preserves moving verses by some of the earliest Buddhist nuns. Many joined after personal tragedy—widowhood, abandonment—or after hearing the Buddha speak. Their poetry brims with relief at newfound freedom from housework, male authority, and unending pregnancies. One famous passage features a nun, Punna, who questions why a brahmin man thinks plunging into an icy river can wipe away evil karma when fish and frogs live there all the time.

Though the mainstream Buddhist establishment still worried about women’s sexuality “tempting” male monks, the personal testimonies in the Therigatha shine a light on an empowering spiritual community where caste and marital status became irrelevant.

Political Upheavals and Wider Influences

As Buddhism and Jainism spread, they did not fully dismantle patriarchy but did create alternate routes for some women. Meanwhile, on the political stage, empires rose and fell. Persia’s Darius I briefly controlled parts of the Indus region. Alexander the Great reached the Punjab before retreating. The Mauryan Empire (c. 322–185 BCE), established by Chandragupta Maurya, became a vast state apparatus. Its most famous ruler, Ashoka (3rd century BCE), embraced Buddhism and promoted tolerance, but the overall patriarchal fabric of society remained in place.

The Laws of Manu and the Ramayana

As the Mauryan Empire declined, repeated invasions in northwest India and the Deccan, alongside the growth of a powerful merchant class, triggered a demand for new socio-legal codifications. By around 200 BCE, a Brahmin scholar named Manu authored a code, later known as the Manusmriti or Laws of Manu, which deeply influenced Hinduism and India’s social order.

The Laws of Manu: Structuring Gender and Caste

The Manusmriti enshrined four primary aims for human life:

- Dharma (duty)

- Artha (wealth/power)

- Kama (pleasure/sexual gratification)

- Moksha (salvation/liberation)

Manu’s framework, however, strongly favored upper-caste men. Women were denied the ability to pursue moksha independently, could not read sacred Sanskrit texts, and were legally tied to male guardians—father, husband, or son—across the life cycle. Marriages were arranged early, and wives were admonished to treat their husbands, regardless of character, as gods. Strict penalties existed for women who had sex outside marriage, especially if it involved a man of a lower caste. In one chilling decree, a woman who slept with a man of a lower caste would be thrown to the dogs.

Despite such harsh rules, the Manusmriti also includes ambivalent passages praising women. It asserts that gods favor households where women are respected. This contradiction—venerating women as mothers while denying them autonomy—continues to mark much of traditional Hindu culture.

Epic Narratives: Modeling Female Conduct

Two monumental Sanskrit epics, both with final forms around the early centuries CE, further elaborated Brahminical values. The Mahabharata—the world’s longest epic—focuses on a great war and emphasizes duty, heroism, and the male warrior ideal. Yet it also recognizes wives’ importance. One passage lauds wives as “the safest refuge” and “half the man,” vital for emotional balance.

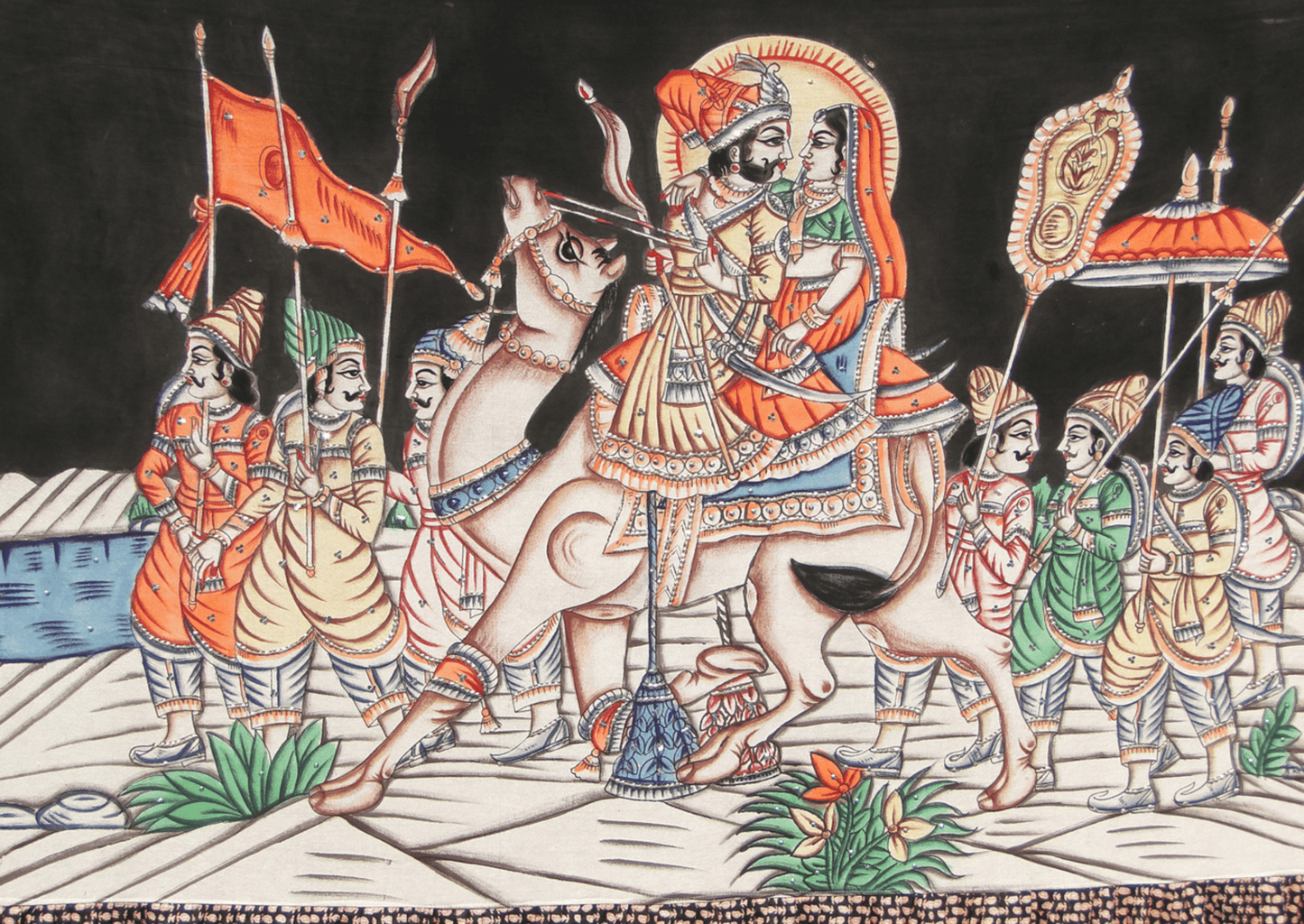

The Ramayana, on the other hand, is more explicitly concerned with modeling female behavior. Queen Sita, the heroine, exemplifies loyalty, chastity, and stoic endurance of hardship—all while remaining subservient to her husband, Lord Rama. Indeed, Sita’s trials (including an ordeal by fire to prove her purity) became a paragon for wifely devotion. Similarly, the classical Sanskrit play Shakuntala by Kalidasa features a heroine who remains unwaveringly loyal to a husband who initially rejects her. In Indian tradition, these narratives set the gold standard for a “good woman,” blending sensuality, faithfulness, obedience, and deep moral strength.

Courtesans: The Educated Outsiders

Strikingly, within this period of increasing constraints on wives, the only women permitted formal education or artistic training were often courtesans. Renowned treatises like the Kamasutra describe the rigorous preparation of these women in multiple arts: poetry, dance, music, literature, even politics. While true of only a minority of privileged courtesans, they commanded a visibility and mobility denied to ordinary wives. Lower-class or enslaved prostitutes, however, experienced far harsher realities, lacking both autonomy and respect.

Conclusion

Even at the height of Brahminical dominance, India remained a tapestry of beliefs and practices. Local goddesses—linked to fertility, rain, and healing—were venerated throughout the subcontinent. Centuries of worship evolved into complex goddess cults venerating Devi in her benign forms (Lakshmi, Sarasvati, Parvati) and fierce ones (Durga, Kali). Tantrism arose, celebrating female energy (Shakti) sometimes in ways that frightened orthodox Brahmins. The bhakti movement, centered on heartfelt devotion, opened new spaces for women’s spiritual expressions. Poets like Mira Bai—revered for her love songs to the god Krishna—continue to inspire women today.

Still, from roughly the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE) onward, patriarchal measures hardened. Women were generally confined to domestic roles, forced to marry early, and rarely allowed to remarry if widowed. Access to Sanskrit learning or formal religious authority was restricted to a small circle of high-caste males. While many ordinary women found dignity in household roles and maternal authority, autonomy and public power were elusive.

In some ways, the repeated tension between revering female divinity and subjugating actual women speaks to a broader paradox in Indian culture. Over millennia, the subcontinent has witnessed myriad local customs and pan-Indian philosophies. It has produced towering female saints, warrior queens, and ordinary women whose songs still resonate with spiritual longing. Yet the structural inequities codified by ancient texts like the Manusmriti have proven remarkably enduring.

Herstory: