The Triumph of Death: The Plague in the Rest of Europe

The final years of the first wave of the Black Death took it far from the shores of France and Italy into Scandinavia, Russia, and remote outposts of the Atlantic.

From the late 1340s to the early 1350s, the Black Death continued its relentless sweep through Europe, claiming vast numbers of lives and overturning social, economic, and spiritual norms in every region it touched. While Italy, France, England, and Germany bear some of the most detailed records of the pandemic, many other corners of the continent—and beyond—also experienced the devastation in unique ways. Whether due to trade patterns, shifting alliances, or sheer happenstance, no land was truly safe from infection, and few places escaped entirely unscathed. Below, we explore how the plague came to Scandinavia, the Faroe Islands, and Russia, look at seemingly “spared” territories such as Poland and the Netherlands, and trace the broader social changes that erupted in the decades after. We also turn our attention to the “Renaissance Plague” and the “Third Pandemic,” which would ensure that plague remained a persistent threat for centuries.

The Plague Arrives in Scandinavia

The year 1349 saw a ship laden with English wool set sail from London, heading north toward Bergen, Norway. Depending on the source, plague either broke out among the crew at sea (leaving the vessel to run aground) or erupted after the ship successfully reached harbor and began unloading. Either way, the result was the same: Bergen became one of the first Norwegian towns to be infected, with the outbreak raging by September. Norwegian chronicles suggest a similarly grim scenario in Oslo, which may have been struck around the same time.

Fast Spread Across Northern Shores

From late 1349 onward, plague radiated through the rest of Scandinavia:

- Sweden: King Magnus II ordered his subjects to fast on Fridays and conduct barefoot processions around cemeteries. Stockholm and Uppsala endured their highest mortalities in winter, indicating that pneumonic plague thrived in the colder months.

- Denmark and Its Overseas Outposts: The disease spread among Danish fishing settlements in Greenland. Yet some inhabitants, wary of supply ships failing to arrive, may have simply abandoned posts and returned to Europe.

- Iceland: Narrowly escaped full-scale infection in 1349 when a pestilence-stricken ship from Bergen could not sail. However, Iceland would not remain lucky forever: in 1402, plague finally struck, wreaking havoc on the island’s population.

- Remote Archipelagos: The Shetlands, Orkneys, Hebrides, and Faroe Islands suffered outbreaks despite their isolation. Fleas on ships or small trading vessels likely carried the bacillus across even these scattered islands.

Russia and Final Phases of the First Pandemic

As the Black Death ebbed in Western Europe, it flared in Russia, attacking regions just as winter took hold. Pneumonic plague, which thrives in cold climates, proved especially lethal. Records are patchy, but references to sudden, deadly “pestilences” near trading posts and major towns persist. By 1352, the pandemic’s first wave was finally losing steam, yet its legacy of destruction had reached across Europe, North Africa, and Asia in barely twenty years.

Surprising Escapes and Later Outbreaks

Medieval accounts describe how plague sometimes annihilated one city while sparing another mere miles away. Some places, like Milan, emerged with far fewer casualties than surrounding regions, possibly due to strict quarantine (the Milanese authorities walled up known plague houses). Meanwhile, the Netherlands largely sidestepped the monumental death tolls seen in France or Germany, though the precise reasons remain unclear. Poland and Bohemia, due to their comparatively lower volume of international trade, likewise appeared to avoid the worst—at least in the initial wave. Unfortunately for them, subsequent plague recurrences were brutal: Bohemia was savaged in 1361, while Poland suffered badly in later outbreaks as trade networks changed.

Unraveling Myths of “Spared” Regions

For decades, some scholars contended that large territories—like Poland—were all but untouched by the 1340s pandemic. More recent research questions this narrative. Certainly, these regions experienced fewer initial plague deaths than, say, Tuscany or England, but they were not entirely immune. Over the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, repeated outbreaks, including the so-called “Renaissance Plague,” tested even those populations that had dodged the initial 1347–1352 onslaught.

The Black Death’s Impact on Society

By conservative estimates, the Black Death eradicated about one-third of Europe’s population between 1347 and 1352—some 50 million people. China, which had endured its own massive mortality, may have lost half its population around the same time. The Middle East suffered similarly staggering losses. Although nineteenth-century historians often downplayed these demographic upheavals, modern scholarship sees the pandemic as a major pivot point, accelerating or altering social, economic, and religious developments.

Agricultural and Demographic Changes

In England, between 30% and 40% of the population died, with higher rates among priests (closer to 45%). Other parts of Western Europe reported similar or even greater mortalities. In Tuscany (Italy), the figure may have reached 50%. Such a drastic loss of life led to:

- A Thinned Population: With fewer mouths to feed, resources like land, grain, and livestock became more abundant—at least for those who survived.

- Wage Increases: Farmers and laborers, suddenly in short supply, could demand higher wages or improved conditions. This shift in the labor market spurred partial disintegration of the manorial system and facilitated the rise of an emerging “middle class” of free tenants, often called yeomen.

- Rural Mobility: Former serfs seized the chance to move freely in search of better terms. Some lords offered freedom from serfdom in exchange for stable rents; others tried (and failed) to enforce old feudal obligations through strict legislation.

Boom in Living Standards

In many regions, especially during the 1350s:

- Better Diets: Fewer people could mean more available food, leading to improved nutrition.

- New Opportunities for Women: Labor shortages opened roles previously closed to women. Brewing, textile production, and other trades welcomed female laborers and entrepreneurs.

- Rise of Technology: The post-plague era saw heightened impetus for mechanical or technological solutions to labor scarcity. Johann Gutenberg’s printing press would appear in the mid-fifteenth century, transforming the dissemination of knowledge.

Artistic and Spiritual Upheaval

The Church’s credibility eroded. Clerics, once seen as divinely protected, died alongside their parishioners in staggering numbers. Their replacements were often younger, less trained, and widely viewed as inferior. Dissenters like the Lollards, Wycliffites, and other heretical or semi-heretical groups gained traction. Mendicant preachers thrived, offering spiritual counsel to communities disillusioned by the established clergy.

Cultural Responses

- Literature and Mysticism: Works like The Cloud of Unknowing and The Ladder of Perfection reflect a more personal, introspective faith, focusing on one’s inner relationship with God. Anchorites and solitary mystics wrote to help believers cope with constant reminders of mortality.

- Macabre Imagery: Paintings and sculptures featuring the Danse Macabre—Death leading the living away—became widespread across Europe. Artists emphasized the transience of earthly pleasures.

- Return to “Excess”: Chroniclers expressed surprise at how, after the worst had passed, survivors often indulged in lavish feasting, drinking, and dressing. Far from learning permanent sobriety, many people embraced hedonism, driven by a sense that life could be snatched away at any moment.

Shift in Language and Education

Because many learned men (especially older professors) had died, universities began offering instruction in the vernacular. Latin and French, formerly dominant in courts and academics, lost ground to local languages. Existing universities vanished, but new ones rose, including those in Prague, Vienna, Krakow, and Florence. In England, Cambridge founded three new colleges, and Oxford two, as younger intellectuals filled the void left by the plague’s heavy toll.

The “Grey Death” and Renaissance Plague

Though the initial wave ended by the early 1350s, plague outbreaks continued for centuries:

- The Grey Death (1361): Also called the “Children’s Plague,” it attacked an already weakened Europe, hitting mortality rates of 20–25% in some areas. Chroniclers noted that it seemed especially harsh on children, though this might be an exaggeration.

- Recurring Epidemics: Further surges flared up repeatedly (1369–71, 1375, and well beyond). By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europeans called them the “Renaissance Plague,” as they coincided with the era’s cultural blossoming. These recurrences were often local and somewhat less deadly than the fourteenth-century catastrophe, yet they still caused devastation in certain cities.

- Co-Infections: In many places, the Renaissance Plague ran concurrently with smallpox (the so-called Red Plague), typhus, or anthrax, compounding the death rate and pushing communities to a breaking point.

Socioeconomic Strains

Ongoing epidemics severely tested governments. In England, Edward III tried to freeze wages at pre-plague levels, triggering widespread labor dissatisfaction. Sumptuary laws were passed to curb “excessive” clothing. When poll taxes were expanded to the poor in 1377, tensions exploded into the English Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. France and parts of the Low Countries witnessed similar uprisings. While the Black Death did not directly “cause” these revolts, it undoubtedly hastened the social transformations (and resulting conflicts) of the late fourteenth century.

The Plague Beyond Europe

The Middle East and North Africa experienced their own disruptions:

- Economic Turmoil: Certain commodities—like shrouds, coffins, and spices used for medicinal or burial rites—skyrocketed in price. Labor shortages mirrored Europe’s experiences, though not always producing feudal breakdown.

- Religious Views: In Islamic societies, plague was typically seen as part of God’s inscrutable plan; there were fewer accusations of moral degeneracy, fewer scapegoating incidents, and relatively little anti-Jewish violence of the kind that erupted in German and French territories.

- Enduring Outbreaks: Plague recurrences also struck the broader Islamic world, continuing well into modern history.

From the Great Plague of 1665 to the Children’s Rhyme

Though overshadowed by the 1348–1352 pandemic, plague still haunted Europe for centuries:

- The Great Plague of 1665: Ravaged London, with up to 10,000 deaths per week at its peak. Famous diaries from Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn capture the eerie atmosphere of deserted streets and constant funeral carts.

- Bird-Beaked Doctors: By the seventeenth century, “plague doctors” wore protective gear lined with wax, accompanied by a beaked mask stuffed with aromatic herbs. These attempts at self-protection were largely symbolic, but they illustrate how people struggled to adapt knowledge gleaned from centuries of repeated outbreaks.

- “Ring a Ring o’ Roses”: A nursery rhyme possibly referencing buboes (“rosy” skin lesions) and posies (herbs carried to purify the air). Although it might have originated later, many associate it with plague times.

- The Village of Eyam: In Derbyshire, 1665, a tailor named George Vicars unwittingly unleashed plague via flea-infested cloth from London. Under the leadership of Reverend William Mompesson, Eyam famously self-quarantined for 14 months, preventing contagion from spreading further but paying dearly: around one-third of the villagers perished.

The Third Pandemic (1855–1959)

An epidemic that began in Yunnan, China, in 1855 ballooned into what historians call the Third Pandemic:

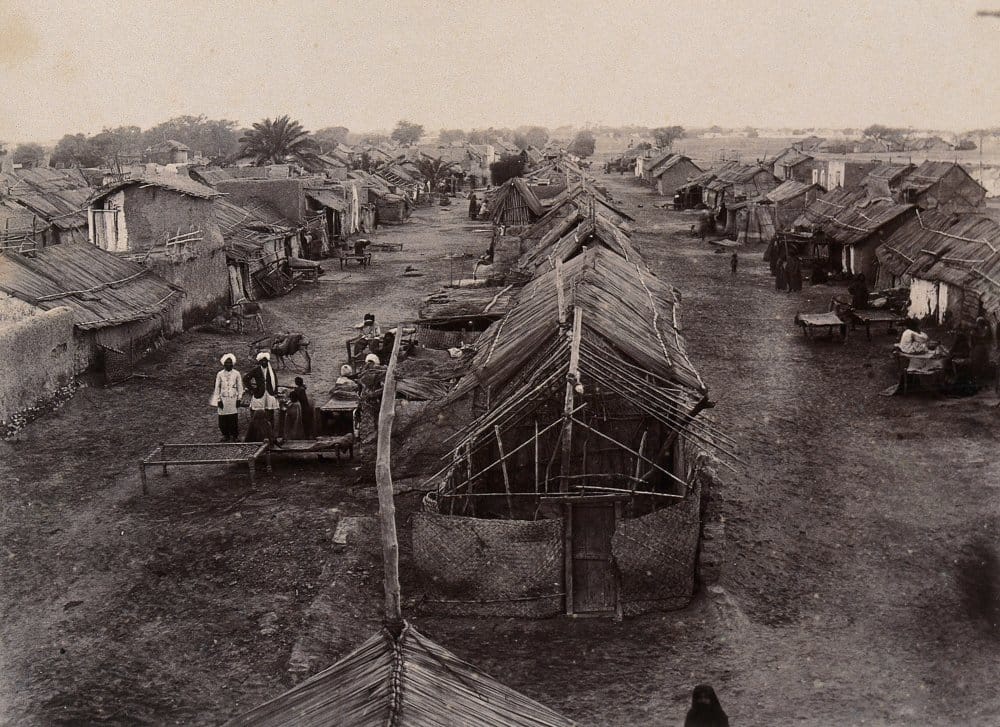

- Hong Kong Outbreak (1894): Estimated to have killed 75% of the local population—some 100,000 deaths in a matter of months. It was here that microbiologists Alexandre Yersin and Shibasaburo Kitasato independently identified the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis.

- Discovery of Rat-Flea Vectors: Paul-Louis Simond soon pinpointed the critical role of rats and their fleas in spreading plague, thus solving a mystery that had confounded medieval Europeans.

- Haffkine’s Vaccine: In the midst of a horrifying outbreak in Bombay (Mumbai), Waldemar Haffkine raced to develop a plague vaccine. Within months of near-round-the-clock work, he successfully tested it on himself and a group of volunteer prisoners.

- Global Spread: Trade routes once again proved decisive. Ships carried plague to India, North Africa, the Middle East, and as far as Hawaii (1899) and San Francisco (1900–1904). Though Western Europe escaped large-scale devastation, port cities like Liverpool, Glasgow, and Hamburg saw small clusters of plague-linked fatalities.

These recurring global eruptions continued well into the twentieth century. The World Health Organization declared the Third Pandemic over in 1959, although occasional cases of plague still arise, particularly in rural parts of Africa and Asia.

Was the Black Death Really Plague?

In recent decades, some scientists and historians have questioned whether the medieval “Black Death” exactly matches modern plague. They note:

- Different Symptoms: “God’s Tokens” (bruise-like blotches), delirious convulsions, and an overwhelming odor from victims are not typical of modern plague outbreaks.

- Speed of Transmission: The Black Death spread across Eurasia in less than 20 years, whereas the Third Pandemic took several decades to reach comparable levels.

- High Mortality: Up to 30–50% mortality in some fourteenth-century cities dwarfs the roughly 3–10% rates in modern plague incidents.

Proposed alternate theories include anthrax, hemorrhagic fever (similar to Ebola), or a “Disease X” that has since vanished. Some even suggest an extraterrestrial virus. Yet most evidence continues to support Yersinia pestis as the prime culprit. Excavations at plague pits, subjected to modern genetic testing, typically yield DNA from the plague bacillus. Moreover, unsanitary conditions in medieval cities—along with human fleas (Pulex irritans)—may have boosted the fatality rate far above modern norms.

Lessons and Legacies

Whether or not a mutation made the fourteenth-century plague especially virulent, the disease reshaped civilizations:

- Lasting Fear of Epidemic Return: Though no outbreak has equaled the scale of 1347–1352, repeated resurgences traumatized generations.

- Socioeconomic Reconfiguration: The labor mobility that followed spurred major shifts, including the decline of feudal structures and a rise in wage labor, proto-capitalism, and a new sense of class identity.

- Religious and Cultural Transformations: Disillusionment with ecclesiastical failings encouraged mysticism, heretical movements, and a reinvigorated focus on personal piety. Art, literature, and architecture sank into dark themes, eventually sparking Renaissance curiosity about mortality and the human condition.

- Foundations of Modern Public Health: Outbreaks forced governments to experiment with quarantines, travel bans, and eventually, advanced sanitation systems. The experiences of plague prompted cautious expansions of medical knowledge that culminated in breakthroughs once modern bacteriology developed.

Even in modern times, plague remains part of the global disease landscape—albeit controlled through antibiotics and heightened hygiene. Countries like Madagascar occasionally experience flare-ups, underscoring that Yersinia pestis did not vanish after 1959. The story of the Black Death serves as a perpetual reminder of how swiftly a microscopic threat can overturn entire civilizations—and how crucial resilience, adaptation, and scientific curiosity are for survival.

Conclusion

The final years of the first wave of the Black Death took it far from the shores of France and Italy into Scandinavia, Russia, and remote outposts of the Atlantic. Although some regions appeared to endure fewer losses at first, the plague spared no continent permanently; later epidemics, including the “Renaissance Plague” and the global “Third Pandemic,” ensured it remained a recurring specter for centuries. Meanwhile, the social upheavals provoked by the initial onslaught—from the dissolution of medieval feudal structures to the stirring of new religious and intellectual movements—transformed the map of Europe and shaped the modern world.

By the time plague faded from its medieval prominence, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia had all undergone profound shifts in demography, politics, religion, and culture. Even the Great Plague of 1665 and the quarantined heroics of Eyam, or the frantic bacteriological discoveries of Yersin and Haffkine in the late nineteenth century, carry echoes of the original fourteenth-century nightmare. The triumph of death in the plague years is thus also a triumph of survival—albeit one purchased at a devastating cost. Should plague or another disease “X” rise again, the lessons of history remain as essential as ever.