The Roman West Fell: Barbarians, Borders, and the End of an Empire

The Western Roman Empire was not destroyed in one swift stroke.

In the fourth and fifth centuries CE, the Western Roman Empire experienced one of history’s most dramatic transformations. Once an unrivaled Mediterranean power, Rome now faced relentless pressure from every direction—from the endless plains of Central Asia to the deserts of Africa and the shores of Northern Europe. In the East, an emboldened Persian Empire launched renewed offensives; in the West, Germanic and other “barbarian” tribes advanced across long, porous borders. At the same time, the Empire’s internal strength had eroded under economic stress, governmental corruption, shifting demographics, and bitter ideological divides.

Below, we look at the final centuries of Roman rule in the West. We will follow the Empire’s struggles on a 10,000-mile frontier, watch as various emperors try—and mostly fail—to hold the line, and witness the eventual fall of Rome as a political center. By 476 CE, barbarians not only controlled large tracts of Roman soil; they also shaped new kingdoms on the bones of Roman civilization.

The Long Frontier—and the Persian Threat

By the mid-fourth century, the Roman Empire’s frontiers formed an enormous arc spanning from the North Sea down to the deserts of North Africa, eastward to the lands of Persia, and all the way north again via the Black Sea. Maintaining security over these vast boundaries—estimated at over 10,000 miles—proved nearly impossible. On one sector alone, the empire confronted the Persians, who had grown powerful enough to threaten Roman defenses in the East. Since the days of Darius I, Persia had been a formidable rival, and by the fourth century CE, the Sasanian kings aimed to restore much of the old Achaemenid territory. Meanwhile, further west in Arabia, tribes of Bedouins lived in relative obscurity; yet within a few centuries, they would conquer vast stretches of territory from both the Romans and the Persians.

In North Africa, along the Empire’s southern flank, a patchwork of tribes—Berbers, Libyans, and Moors—stood ready to exploit Roman weaknesses. Although the Empire’s African provinces were valuable economically (particularly for grain), they were too large to defend perfectly, and local forces often felt neglected when Rome’s attention shifted toward crisis after crisis elsewhere.

Gaul (roughly modern France), with its increasingly Romanized cities and substantial economic development, had outpaced Italy in some respects. Yet this region lay perpetually vulnerable to Germanic incursions from beyond the Rhine. Germany itself was home to a cluster of tribes—Franks, Alemanni, Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, Angles, Saxons, and others—always on the move in search of more fertile land and a better life. Spain, ringed by mountains and seas, seemed secure, but Rome’s control here, too, would crack under waves of invasion. By the early fifth century, barbarian armies crossed the Pyrenees and brought chaos to what had been a relatively quiet frontier.

Even across the Channel, Britain faced the Picts from modern Scotland, Irish raiders, and Saxon or Norse pirates. The legions sent to defend Britain were never numerous, and when Rome withdrew them for other emergencies, British cities and forts found themselves dangerously exposed.

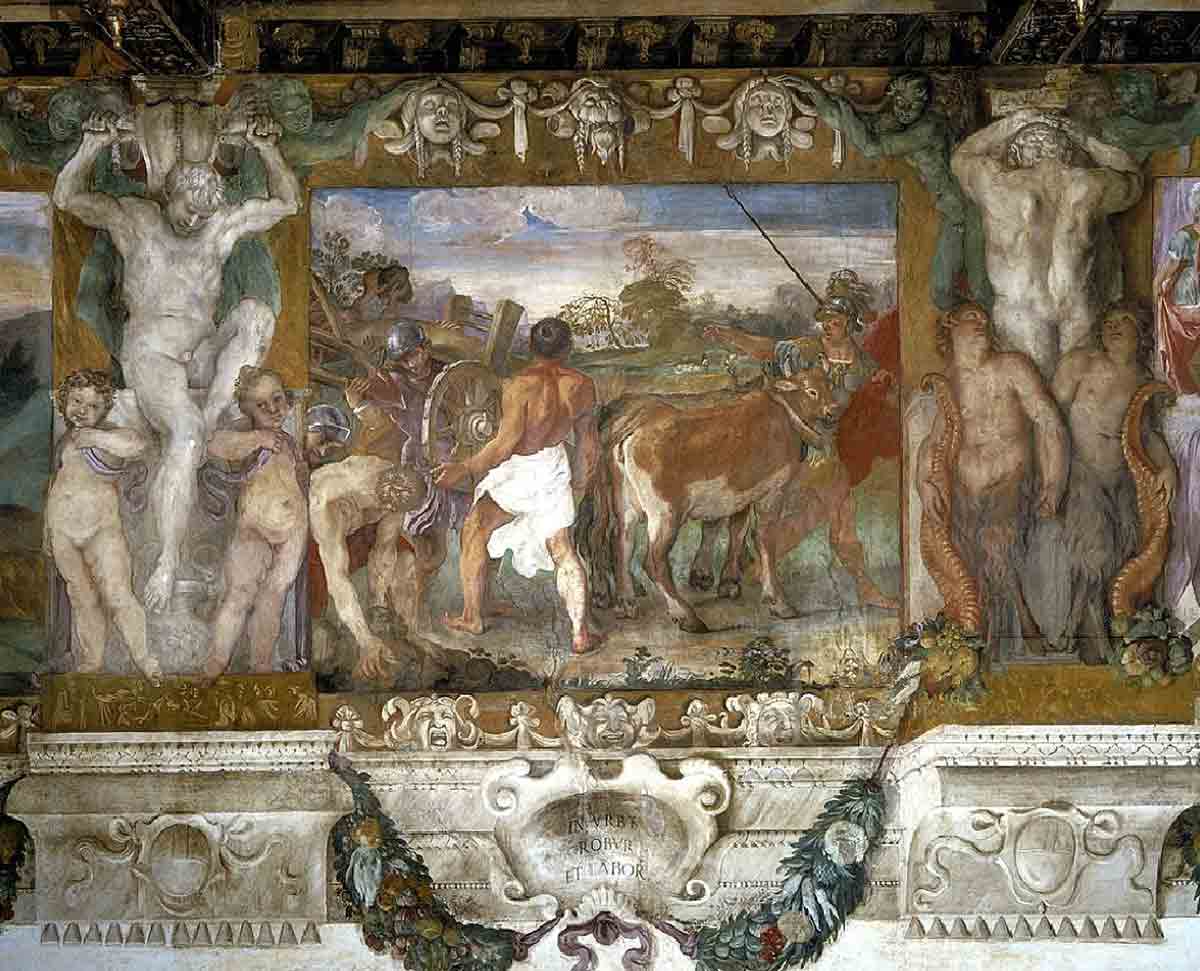

“Barbarian” in Roman parlance originally meant “foreigner,” derived from Greek and Sanskrit roots implying a rough, unlettered outsider. By the fourth century, however, many of these Germanic tribes had long been interacting with Rome through trade, treaties, and war. They had learned Latin script, adopted stable laws, and gained a certain respect for Roman ways. Their household morals, especially surrounding marriage, in some cases exceeded the standards of Romans and Greeks who practiced a more lax (or more varied) moral code. On the other hand, Germanic “barbarian” life was often harsh, with brutal forms of justice, frequent feuding, and an individualistic streak that sometimes clashed with Roman discipline.

Rome had admitted certain groups of barbarians onto imperial soil for decades, in part to repopulate war-torn provinces and to refill the ranks of the army. By the end of the fourth century, regions like the Balkans and large swaths of Gaul were predominantly Germanic in population. The Roman army itself was heavily German, and the infiltration of these new peoples, while strengthening certain military units, simultaneously frayed the unity of Latin and Greek-speaking Romans. Once, Roman culture had been dominant enough to “Romanize” newcomers. Now the empire’s internal cohesion was so weakened that barbarians only lightly adopted its customs or language before carving out domains of their own.

The Great Influx: Huns and Goths

A massive catalyst for change arrived around the mid-fourth century: the Huns. Originating on the steppes north of the Caspian Sea (east of modern Russia), these horse-riding nomads possessed an unparalleled ferocity. Their swift cavalry and skill with bow and arrow terrified settled communities. They captured the Alani (another nomadic group), swept into the Ostrogothic lands in modern Ukraine, and forced the Ostrogothic king Ermanaric to defeat or suicide. The Ostrogoths either surrendered or fled. Those who fled found temporary shelter with the Visigoths north of the Danube—until the Huns came for them as well.

Desperate for sanctuary, the Visigoths appealed to Emperor Valens for permission to settle in Roman territory. The request was granted—but under strict conditions: The Goths were to give up their weapons and provide hostages, particularly their youths. Roman officials swiftly violated the agreement, forcing the Goths to surrender their children into virtual slavery while also swindling them for food at exorbitant prices. Some starving Goths sold their own sons and daughters for scraps of meat. Soon, Gothic outrage erupted into open war.

Valens assembled an army, composed partly of barbarian auxiliaries, and advanced against the Goths near Hadrianople. The result was a catastrophic Roman defeat, sometimes compared to the famous Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE. Two-thirds of the Roman army were killed, including Emperor Valens, who was rumored to have died in a cottage the Goths set on fire. The fiasco destroyed the notion that Roman infantry tactics were automatically superior; cavalry now came to dominate warfare for centuries. After Hadrianople, vast numbers of Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Huns roamed the Balkans almost unopposed.

Political Revival and Internal Strife: 364–408

Rome’s fortunes rose briefly under capable emperors who tried to reconstitute the empire’s might:

- Valentinian I (364–375 CE): Chosen emperor by the army and Senate, he gave his brother Valens control of the East. Valentinian fortified the frontiers, built up the army, improved the coinage, reduced taxes on the poor, and—rare among his contemporaries—insisted on freedom of worship. He died prematurely, leaving a precarious succession.

- Gratian (375–383 CE): Valentinian’s son, he started well but lost himself in distraction and delegated power to suspect officials. A general named Maximus overthrew him, prompting further instability.

- Theodosius I (379–395 CE): A Spaniard by birth, Theodosius possessed both military talent and a strong adherence to Nicene Christianity. He reached accommodations with the Goths (some serving as allies in his army) and reunited the empire briefly under his sole rule in 394, defeating various usurpers. However, he was also responsible for cruel acts, such as the massacre in Thessalonica in 390, where thousands were killed in revenge for the murder of his governor. Famously, Bishop Ambrose of Milan compelled Theodosius to do public penance for this crime. When Theodosius died in 395, he left two young sons: Honorius (ruling the West) and Arcadius (ruling the East), both ill-equipped to handle the rising crises.

- Stilicho and Alaric

In the West, power fell into the hands of a skilled Vandal general, Stilicho, who served as regent for Honorius. Meanwhile, the Visigothic chieftain Alaric, unpaid for his services and fueled by the grievances of his people, conducted raids into Greece and later into Italy. Stilicho halted Alaric’s forces on multiple occasions (notably at Pollentia, 402 CE) but was undermined by court intrigue. Olympius, jealous of Stilicho’s influence, persuaded the paranoid Emperor Honorius to arrest and execute him in 408 CE. With Stilicho gone, Alaric saw no remaining obstacle to direct invasion.

The Sack of Rome and Barbarian Kingdoms

Within months of Stilicho’s execution, Alaric crossed the Alps into Italy once more. He threatened the city of Rome itself. The Senate scrambled to negotiate, but Alaric demanded an enormous sum in gold, silver, and luxury goods. Initially, Romans resisted, but famine soon reduced them to desperate measures—reports circulated of parents cooking and eating their own children. Eventually, they agreed to pay Alaric off, but fresh disputes arose. Alaric returned in 410 CE. This time, slaves sympathetic to the Goths opened the gates. For three days, Rome endured terrifying pillage, though Alaric prohibited the destruction of churches. It was the first time in 800 years that an enemy had captured Rome.

Alaric did not intend to settle in Rome; he wanted to move on to southern Italy and possibly Sicily. However, he died suddenly that same year. His successor, Ataulf, married Honorius’s half-sister, Galla Placidia, and established a Visigothic kingdom in southwestern Gaul (capital at Toulouse). Although nominally loyal to the Empire, the Visigoths effectively governed themselves.

The Vandals, along with the Alani and Suevi, crossed the Rhine in 406 CE and ravaged large parts of Gaul. They soon poured into Spain, seizing territory and upending centuries of Roman rule. The Western government enlisted Visigothic help to restore order, and for a time it appeared that Spain might be salvaged. But in 429 CE, the Vandals under King Gaiseric sailed to North Africa. Facing minimal imperial resistance, they took Carthage in 439 CE, seizing one of the Empire’s most valuable provinces, famed for its grain exports. Gaiseric then built a powerful navy, raiding across the western Mediterranean with impunity.

Originally from Central Asia, the Huns had formed a confederation in Eastern Europe. By the mid-fifth century, they rallied under a single king: Attila (“Little Father” in Gothic). Short, broad-chested, and possessed of a fearsome aura, Attila extorted tribute from both Eastern and Western courts. In 451 CE, he invaded Gaul with a massive force, only to be checked at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields near Troyes, where a coalition of Romans and Visigoths claimed a costly victory. Attila then turned to northern Italy in 452 CE, ravaging cities such as Aquileia. The city was so thoroughly destroyed that it never recovered. When Attila seemed poised to strike Rome, Pope Leo I met him in person. Remarkably, Attila withdrew—possibly because his army had suffered disease, supply problems, and the looming threat of additional Roman forces. Within a year, Attila died suddenly, and the great Hun empire dissolved amid internal rivalries and revolt among subject tribes.

The Unraveling of the Western Empire

By the mid-fifth century, the Western Roman Empire was in political chaos. Emperors came and went with dizzying speed:

- Petronius Maximus (455 CE): Came to power after the assassination of Valentinian III, but lasted only a few months before Gaiseric and his Vandals sacked Rome again.

- Avitus, Majorian, Severus, Anthemius, Olybrius—each occupied the throne briefly, often manipulated by powerful generals of barbarian background, such as Ricimer the Visigoth.

- Julius Nepos and Glycerius also ruled in fragments. Nepos was soon overshadowed by another Pannonian general, Orestes, who placed his own son, Romulus Augustulus, on the imperial throne in 475 CE.

Thus, a string of weak emperors, overshadowed by foreign generals, held nominal power in the West. Meanwhile, the Eastern Empire continued under separate emperors based in Constantinople. Some Western cities tried to maintain everyday life, but the rural and military infrastructure needed to protect them eroded rapidly. A complex pattern of local aristocrats, bishops, and barbarian warlords filled the vacuum.

The Fall of Rome or the Birth of a New Order?

The final, symbolic event was the rise of Odoacer, a general of the Heruli, Rugii, and other Germanic bands once associated with Attila’s Huns. When Orestes refused to give these soldiers a third of Italy’s lands, they killed him, deposed Romulus Augustulus, and elevated Odoacer as their king (476 CE). Odoacer recognized the Emperor Zeno in Constantinople as the theoretical ruler of a “unified” empire but effectively governed Italy as an independent realm. This date—476 CE—has traditionally marked the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire. Yet many contemporaries saw it as a unification under the East, not necessarily the disappearance of Rome’s legacy.

Why did Rome fall in the West? Historians debate the reasons, pointing to economic exhaustion, demographic decline, high taxation, reliance on foreign troops, political corruption, and a weakening of civic spirit. Over time, large estates absorbed smaller farms, fewer citizens served in the legions, and impoverished towns watched their grain shipments dwindle. The enormous frontier was impossible to guard without an army of half a million men, and that army no longer existed in a cohesive Roman form.

Culturally, Rome’s decline in the West paved the way for new ethnic and political fusions. Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, and Franks adopted elements of Roman law, administration, and Christianity, even as they formed separate kingdoms. In North Africa, Gaiseric’s Vandals built a maritime power, harassing the Mediterranean lanes once dominated by Roman fleets. In Spain, the Suevi and Visigoths became catalysts for new medieval societies. In Gaul, the Franks under Clovis would soon rise to reshape the region.

Moreover, many “barbarians” admired Roman civilization—Alaric, Attila, and Theodoric the Ostrogoth all sought legitimacy through alliance with Roman elites. Far from annihilating the Roman world, these new rulers preserved and repurposed many aspects of Roman governance, art, architecture, and religion. Over centuries, local Germanic tongues and Latin intermingled, forging the early romance languages in areas like Gaul (modern French) and Hispania (modern Spanish).

Another key dimension of the fall was the transformation of religious institutions. Christianity, already the dominant faith in the empire, rose to social and cultural prominence as secular power crumbled. Bishops and monasteries took responsibility for welfare, literacy, and justice, thereby preserving elements of Greco-Roman knowledge in monastic scriptoria. When barbarian rulers recognized the Church’s importance as a unifying force, they often converted (at least officially) to Christianity. This fluid convergence of barbarian vigor and Roman heritage laid the foundation for the medieval West.

Conclusion: An End, Yet Also a Beginning

The Western Roman Empire was not destroyed in one swift stroke; it decayed over centuries until barbarians stepped in to fill power vacuums and shape new states. The famous date of 476 CE—when Romulus Augustulus was deposed—carries more symbolic weight than immediate historical consequences. Nevertheless, it serves as a convenient demarcation between antiquity and the early Middle Ages in the West. Italy would see further conflicts, from Odoacer’s reign to the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Theodoric, and eventually the Lombard invasions. Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire, based in Constantinople, survived another millennium, preserving Roman law, administration, and culture in Greek form.

What collapsed in the West was primarily the ancient Roman state apparatus—its professional army, centralized taxation, and bureaucratic governance. The traditional municipal culture weakened, major trade routes frayed, and the once mighty city of Rome dwindled. In its place arose patchwork kingdoms that combined Roman legacy and Germanic custom, eventually giving rise to feudal societies. Civilization, though battered, did not disappear; it evolved into something distinctly medieval. Latin continued as a language of learning and liturgy, Roman law and infrastructure shaped emerging polities, and Christian bishops filled civic leadership roles that had once been the domain of senators. Out of Rome’s ashes, the seeds of modern Europe took root.

The “fall of Rome,” therefore, symbolizes more than ruin. It heralds the transformation of a vast ancient empire into a collection of medieval realms, each influenced by Roman heritage in law, religion, and social organization. As chaotic as the transition appears—pillage, famine, city walls crumbling, emperors assassinated—history reveals this was also a foundation-laying moment, a gateway to the medieval world that would carry forth much of Rome’s soul into new forms. The once-mighty capital might have fallen to Alaric, Genseric, and Odoacer, but its grand legacy persisted through the languages, laws, beliefs, and structures that shaped Europe for the next thousand years.