The Furies: Ancient Greek Goddesses of Vengeance

Despite their terrifying nature, the Furies were also objects of worship throughout ancient Greece

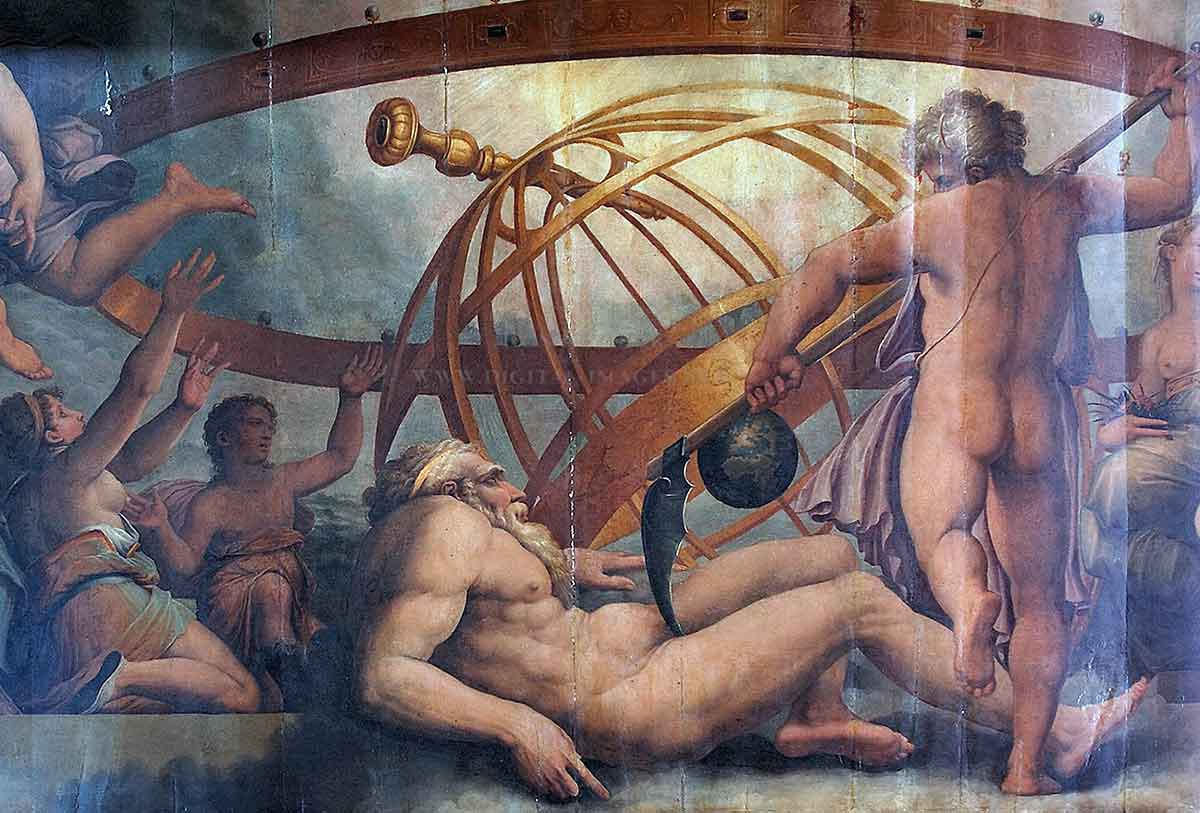

The Erinyes, better known as the Furies, were formidable goddesses in Greco-Roman mythology, embodying vengeance and retribution. They relentlessly pursued those who committed egregious crimes, particularly against family, driving them to madness until they atoned or met their demise. These terrifying figures, often depicted with wings, serpents, and cloaked in darkness, represent the primal human desire for revenge and the consequences of unchecked violence.

Origins Rooted in Violence and Primordial Power

The name "Erinyes" originates from the Mycenaean period, with its meaning debated among scholars. Interpretations range from "strife" and "to hunt or persecute" to "one who provokes struggle." The Romans knew them as the "Dirae" (ominous ones) and "Furiae" (frenzied ones), the source of the name "Furies." Their origins are as dark and ancient as the concepts they represent.

Hesiod's Theogony offers a compelling origin story, linking the Furies directly to primordial violence. They were born from the blood of Uranus, the sky god, after his son Cronus castrated him at Gaia's urging. This act, a brutal instance of familial violence and vengeance, mirrors the very crimes the Furies would later punish. The simultaneous birth of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, from Uranus's castrated genitals adds a layer of symbolic complexity, juxtaposing creation and destruction, love and vengeance.

Other accounts link the Furies to Nyx, the goddess of night, emphasizing their connection to darkness, fear, and the underworld. Some traditions name them daughters of Hades, the god of the underworld, or of Hades and Persephone, solidifying their association with death and the afterlife. These varying accounts highlight the multifaceted nature of the Furies and their deep roots in the primordial forces of the cosmos.

Agents of Justice and Instruments of Madness

The Furies' primary function was to punish the guilty, particularly those who committed acts of impiety, violated hospitality laws, committed perjury, or, most importantly, shed the blood of family. "Blood guilt," the pollution of the soul caused by such acts, particularly the murder of parents or elders, demanded ritual purification. If atonement wasn't achieved, the Furies pursued their targets relentlessly, inflicting madness, blindness, and ultimately dragging them to the underworld. Crucially, their vengeance was indiscriminate, applying even to accidental killings, highlighting the absolute nature of blood guilt in ancient Greek thought.

Beyond their punitive role, the Furies also served in the underworld. They assisted in purifying the souls of the newly deceased and acted as jailers and torturers of the eternally damned in Tartarus. Their influence extended to fate itself, although distinct from the Moirai, the fates. They shaped the destinies of those doomed to lives of suffering and guarded against excessive human knowledge of the future. Their presence permeated every aspect of life and death, ensuring that justice, in its own brutal form, was ultimately served.

The Furies were invoked in oaths, their name adding weight and consequence to promises. Lying or breaking an oath sworn by the Furies risked attracting their wrath, demonstrating the deep respect and fear they inspired.

The Faces of Vengeance: From Monstrous to Kindly

While early accounts offer no fixed number or names for the Furies, three eventually emerged as dominant figures: Tisiphone (avenger of murder), Alecto (unceasing anger), and Megaera (the envious one). Their terrifying reputation led to the adoption of euphemistic titles, such as "Eumenides" (the well-meaning ones) and "Semnae" (the august ones), perhaps an attempt to appease these powerful goddesses.

Depictions of the Furies evolved over time. Early portrayals presented them as monstrous figures resembling the Gorgons, with serpents in their hair, blood-dripping eyes, and draped in black. Later representations, while still formidable, softened their image, portraying them as solemn maidens of the grave, often with hunting gear and snake crowns, a reminder of their terrifying origins. This shift reflects a gradual evolution in the perception of the Furies, from purely monstrous avengers to more nuanced figures of justice.

Woven into the Fabric of Myth

The Furies appear in numerous myths, embodying the consequences of transgressions, especially against family. They pursued Medea after she murdered her brother, tormented Oedipus for killing his father and marrying his mother, and drove Alcmaeon to madness after he avenged his father by killing his own mother. These stories illustrate the inescapable nature of blood guilt and the Furies' relentless pursuit of justice.

Perhaps the most famous myth involving the Furies is that of Orestes, who killed his mother Clytemnestra to avenge his father Agamemnon. Driven mad by the Furies' relentless pursuit, Orestes sought refuge with Apollo, who then directed him to Athens for the first-ever murder trial. This trial, with Apollo as the defense and the Furies as the prosecution, culminated in Orestes' acquittal thanks to Athena's intervention. This landmark judgment established a system of justice that superseded the raw vengeance of the Furies, leading to their appeasement and eventual worship in Athens.

From Fear to Reverence: The Cult of the Erinyes

Despite their terrifying nature, the Furies were also objects of worship throughout ancient Greece. Sanctuaries dedicated to them existed in Athens, Colonus, and Ceryneia, with offerings of black sheep, flowers, and libations of honey and water. The festival of Eumenideia, held in their honor, further demonstrates the complex relationship the Greeks held with these powerful goddesses.

Their transformation from monstrous avengers to revered deities, especially in Athens after Orestes' trial, underscores the evolution of Greek thought on justice and the importance of ritual appeasement in maintaining societal order. The Furies remain a potent symbol of the enduring power of vengeance, the importance of family ties, and the complex relationship between justice and retribution.