The Greek Seer: Divination, Healing, and Authority in Ancient Greece

Combining hereditary lineage, a repertoire of divinatory techniques, and personal magnetism, seers occupied a singular niche in Greek society.

In ancient Greece, the term mantis described an expert diviner—someone who interpreted divine signs and communicated the will of the gods to mortal communities. While modern parallels might compare them to psychic mediums, fortune-tellers, or even homeopathic healers, these analogies fall short. Ancient Greek seers neither claimed to “tell the future” in a modern sense nor professed powers cut off from the gods’ dispensation. Instead, they saw themselves as vessels of divine insight, drawing upon a deity’s inspiration, often Apollo’s, to relay information and warnings.

The “seer” (mantis) was not a low-level religious performer; in many cases, they were considered the highest authority in ritual and religious matters. Military generals, city-states, and powerful leaders would regularly employ seers to interpret omens and guide the timing of battles or voyages. Whether reading bird signs (augury), examining entrails (extispicy), or spotting unusual portents (like eclipses or lightning), the seer’s practiced eye and “god-given” insight determined which course of action aligned with the divine will.

Learn the art of seers in Ancient Greece

Etymology and Meanings of Mantis

The word mantis likely stems from an Indo-European root (men-), connoting a “special mental state” or “altered consciousness.” Plato remarked on the close relationship between mantis (seer) and mania (madness)—both words tied to men-. From an etymological standpoint, a mantis was originally someone who prophesied in an inspired trance. While several other Greek words—theopropos and thuoskoos, for instance—can mean “seer,” mantis remained the dominant term, attesting to its centrality in Greek literature and society.

By the classical period (5th–4th centuries BCE), people referred to the seer’s craft as mantikê technê—literally, “the art of divination.” Yet even as early as Homer’s epics, we see evidence that seers were regarded as specialists akin to carpenters or doctors. The difference was that a mantis derived unique authorization from the gods themselves, whereas skills like carpentry or healing could be taught and practiced without supernatural empowerment. Solon once wrote that “another has been made a seer by lord Apollo,” illustrating that, unlike an ordinary profession, seercraft needed a divine bestowal of insight.

Craft and Charismatic Inspiration

Greek religion recognized both “technical” divination (bird signs, entrail reading, and other systematic methods) and “inspired” prophecy, often involving trance or possession by a god. On the one hand, Greek seers developed an entire repertoire of techniques—studying the shape of animal livers, reading portents in the skies, or analyzing the flow of sacrificial blood. On the other hand, certain seers, especially those at oracular centers like Delphi, relied heavily on altered states of consciousness. The Pythia at Delphi was famously possessed by Apollo when delivering her responses. Aeschylus called Cassandra “a seer” as well, showing that even female prophets working in inspired states fell under the broader mantle of mantis.

In everyday life, seers were mobile practitioners with an expansive scope of authority. They were consulted to interpret signs or preside over sacrificial rituals before critical events such as battles or voyages. Intriguingly, they were also believed to handle various forms of healing and purification. Any problem attributed to a supernatural cause—from mysterious plagues to mental madness—was within a seer’s purview. Both literature and historical sources depict “migrant charismatic specialists” who roamed the Greek world, from the Peloponnese to Asia Minor, offering their expertise to individual clients, city-states, or powerful rulers. Their success, and often the size of their fees, depended on their perceived ability to gain favorable signs from the gods.

Healing, Purification, and Broad Competence

Beyond interpreting omens and augury, Greek seers frequently performed roles akin to healers or “religious doctors.” The archetypal example is the legendary Melampus, whose mythic feats included curing the women of Argos of madness. Similar stories involve seers who purified entire armies, cities, or individuals. In Aeschylus’s Eumenides, the god Apollo is addressed as “healer-seer” (iatromantis), bridging the connection between oracular insight, ritual expertise, and therapeutic functions.

As such, seers represented something more than private fortune-tellers. A well-respected mantis was often society’s first resource in times of crisis—whether it was plague, a sign of divine wrath, or the need to evaluate an unexpected event like an earthquake. Plato, in his Republic, lumps seers, beggar-priests, and sorcerers together, criticizing them for promising too much to the wealthy. But the attack itself suggests just how pervasive and wide-reaching a seer’s reputation could become. Even if some seers’ practices had overlapping qualities with more dubious “magical” rituals, the respected mantis typically stood out as an accredited figure of religious guidance.

The Importance of Family Descent

One of the most striking features of the Greek seer’s profession is the frequency with which it passed down within families. Famous clans, such as the Melampodidae, Iamidae, Clytiadae, and Telliadae, traced their lineage back to mythical or semi-divine ancestors like Melampus or Iamus. These foundational figures, said to have originally received the gift of prophecy from Apollo or another deity, anchored a family’s prestige in claims of direct, inherited inspiration.

- Iamidae (from Elis) were among the most prominent. Pindar’s poetry recounts the story of their legendary ancestor Iamus, who received the “twofold treasury of divination”—the ability to hear Apollo’s true voice and the license to establish an oracle on Zeus’s altar at Olympia.

- Melampodidae traced their ancestry to Melampus, a seer-healer revered for curing madness and facilitating major mythic events. Over centuries, numerous families claimed descent from Melampus, using his name to bolster their credibility as diviners.

Possessing a storied pedigree conferred immediate authority. Sizable fees, stable patronage, and opportunities for fame often followed. Yet family lineage was not always above question. Herodotus mentions seers claiming ancestry to secure lucrative employment throughout Greece. While some genealogies were likely genuine, others could be opportunistic fictions. Regardless, the cultural context made a bloodline from a mythic seer a priceless calling card.

War, Sacrifice, and the Seer’s Influence

Warfare in ancient Greece typically involved the presence of one or more seers. Before any battle, Greek armies would perform campground sacrifices (hiera) and battle-line sacrifices (sphagia). The seer inspected the entrails or observed the victims’ final movements, thereby deciding whether the gods favored battle. Famous examples include:

- Tisamenus of Elis, an Iamid seer, who demanded Spartan citizenship as payment for his services. He eventually guided Sparta to five critical victories, including the battle of Plataea in 479 BCE, forging a reputation as one of the most successful seers in Greek history.

- Hegesistratus of the Telliadae served the Persian general Mardonius, illustrating that even foreign powers coveted Greek seers. Despite questionable loyalties, the Greek world recognized his skill in extispicy and manipulation of sacrificial omens.

Generals or entire city-states cultivated relationships with such specialists. Because these seers did not belong to a single state institution, they could switch allegiances if another employer offered more attractive terms. This freedom also distinguished them from their counterparts in the ancient Near East, like Babylonian or Assyrian diviners, who were tightly bound to royal courts.

Outside Influences: The Ancient Near East and Beyond

Modern scholarship has long acknowledged that many forms of Greek divination—especially reading entrails (extispicy)—originated in the ancient Near East, most probably between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE. Yet Greek writers themselves believed the tradition was homegrown or perhaps imported from Egypt. Playwrights, poets, and historians of the classical era rarely conceded any Mesopotamian origin. Instead, local myths credited culture-heroes like Prometheus or Melampus with teaching Greeks the divine craft.

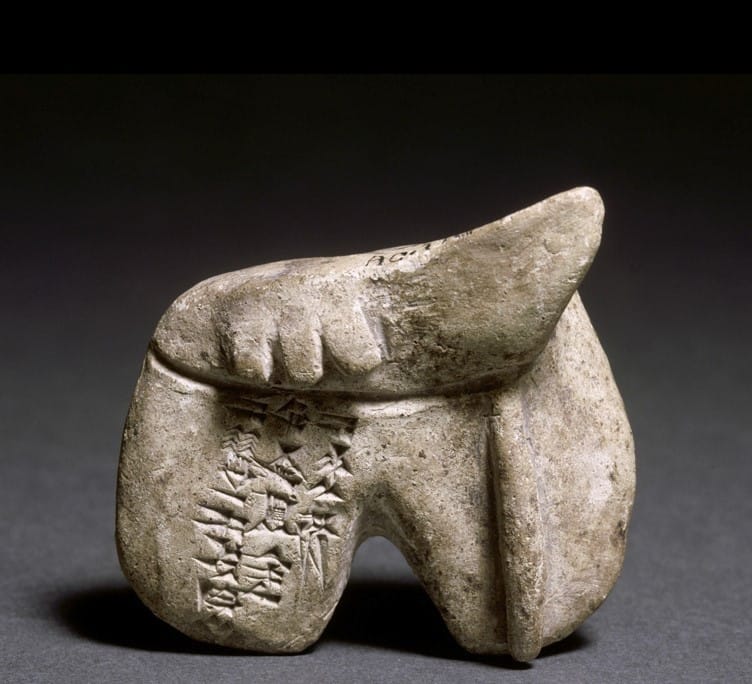

In Babylon and Assyria, divination was a sophisticated, state-supported discipline. Diviners (bārûs) consulted massive archives of omen texts, including thousands of protases (“If this sign appears, then that outcome follows”). They meticulously memorized sequences of favorable or unfavorable patterns in the liver or other organs of sacrificed animals. By contrast, Greek seers relied less on textual compendia and more on personal insight, training, and supposed divine inspiration. No Greek parallels to Mesopotamian clay liver models have been found, underscoring that Greek seercraft, while derived in part from the East, evolved a simpler, more mobile approach.

Female Seers in Ancient Greece

The pantheon of Greek divinatory tradition is not exclusively male. Though overshadowed by the Pythia at Delphi, there were itinerant female seers as well. Legendary figures like Manto (daughter of Teiresias) appear in Greek myths, and we have occasional historical references to women offering oracles and services similar to male seers. For instance:

- Plato’s Diotima, though perhaps fictional, was presented as a wandering prophetess credited with averting a plague from Athens for a decade.

- Satyra, a female seer from Larissa in Thessaly, is attested on an epitaph dating to the 3rd century BCE.

While limited evidence survives, these scattered references indicate that women, too, could practice technical or “artificial” divination, traveling like their male counterparts in search of clients. Just as with male seers, lineage or claims of divine favor would have boosted their authority.

Books on Divination and Seers’ Training

In the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, written works on divination began to circulate—often attributed to well-known intellectuals or specialists. Scholars such as Antiphon supposedly produced texts on the interpretation of dreams, while Philochorus wrote volumes titled On Divination and On Sacrifices. These works likely blended historical anecdotes, mythic genealogies, and examples of famous omens rather than providing straightforward “how-to” manuals. Seers guarded their knowledge and cultivated an air of mystery surrounding their craft; it would have undermined their prestige to publish standardized instructions.

A curious anecdote from Isocrates mentions a certain Thrasyllus, who inherited books from the seer Polemaenetus. Whether these books truly contained a comprehensive guide to extispicy or were more akin to personal notebooks remains unclear. Either way, no matter how many written texts existed, successful seers depended greatly on personal charisma—persuading their audience that they possessed insight beyond what any ordinary person, or mere reader of texts, could obtain.

The Seer and Other Religious Roles

Seers vs. Priests

A common mistake is to conflate manteis (seers) with hiereis (priests). In reality, these were distinct roles. Priests in ancient Greece often held office by virtue of civic appointment, hereditary right, or purchase from the state. Their responsibilities lay in managing sanctuaries, overseeing rituals for the gods they served, and maintaining temple property. Seers, by contrast, were freelance experts in divine signs. Many traveled from city to city, offering their services independently. While a priest’s prestige rested on the importance of the sanctuary, a seer’s reputation soared or sank on the accuracy of their divinatory skill.

There are, however, instances where this line blurs. Members of the famous Iamidae and Clytiadae served as permanent religious functionaries at Olympia, caring for Zeus’s altar and overseeing specialized oracular ceremonies. But generally, the seer’s remit extended beyond any single locale or institution.

Seers vs. Chresmologoi (Oracle-Singers)

Another group occasionally confused with seers were the chresmologoi, who specialized in collecting, interpreting, and chanting oracular verses said to be from figures like Musaeus or Bacis. While the seer typically derived insights from fresh omens—sacrificial entrails, dreams, portents—the chresmologos looked to existing texts or oracular poems. In times of crisis, city-states might consult both. For example, during the Persian invasions, Athenians heard from professional reciters of prophecies as well as from seers who sacrificed animals and observed signs on the battlefield.

Despite overlaps in interpretive skill, the two roles were viewed differently in Greek society. Seers often achieved higher status, while comedic playwrights mocked chresmologoi as charlatans peddling recycled oracles. Some comedic plays even belittle recognized seers, calling them “chresmologoi” as an insult. In short, real-life boundaries were fluid: a performer or religious expert might adopt whichever title seemed beneficial. But classical sources (like Herodotus and Euripides) draw a fairly sharp line between the sacrificial diviner (mantis) and the oracle-chanter (chresmologos).

Magic, Sorcery, and the Mantis

Greek literature occasionally lumps seers together with magicians (magoi), sorcerers (goêtes), and wandering priests (agurtai). This blending is most notable in Plato’s dialogues, where he condemns “beggar priests and seers” who use incantations to beguile wealthy clients. Yet in practical social terms, these categories had different connotations:

- Seer (mantis): Typically respected, especially if backed by a famed lineage or recognized successes in war.

- Magician (magos) and sorcerer (goês): Terms of reproach, suggesting an unsanctioned manipulator of supernatural forces. To call a seer a magos was an insult—accusing them of “coercing” gods rather than legitimately interpreting their signs.

- Beggar priest (agurtês): Often ridiculed as a wandering ritualist who sold dubious charms or “purifications.”

These categories overlapped because anyone could claim (or deny) a certain title; the line between legitimate diviner and shady spellcaster was open to constant renegotiation. Nonetheless, classical authors typically portray a good seer as one who persuades or appeases the gods with sacrifices and prayers, rather than “binding” or forcing them.

This distinction coincides with a broader debate on “magic vs. religion,” famously described by anthropologists as the difference between coercing divine powers (magic) and supplicating them (religion). Yet in Greek society, the boundary was far from absolute. Sacrifice itself can be read as an attempt to influence deities; the difference was whether one operated within recognized civic frameworks or in suspect, marginal contexts. Since seers often served armies or city-states, their public role was more respectable. Even so, Plato’s critiques highlight how easily seers could be caricatured as manipulative sorcerers.

Mastery of Signs and Social Standing

A key question emerges: Why pay high fees to hire a seer if anyone could study bird signs or the shape of an animal liver? The answer lies in the seer’s charisma and the public’s belief that certain individuals uniquely “embodied” divine favor. Homeric epics already depict the seer Calchas as one “by far the best of bird interpreters,” hinting at an innate ability surpassing normal human skill. Greek communities believed a talented mantis not only decoded signs reliably but also, in some mysterious way, attracted favorable omens. When circumstances were dire or armies faced imminent battle, generals wanted a seer who could assure the gods’ blessing.

Furthermore, “failed” seers paid a steep price in reputation. Because high-profile predictions were tested by unfolding events, being wrong could destroy a career—or worse. Conversely, those who predicted success and actually delivered it enjoyed lasting fame. Through repeated triumphs, certain families became legendary repositories of mantic insight, ensuring that each new generation inherited that aura of divine connection.

The Enduring Legacy of the Ancient Greek Seer

The ancient Greek seer stood at a crossroads of religion, social authority, and personal charisma. Neither priests nor mere “fortune-tellers,” seers commanded respect through a unique blend of technical skill—extispicy, augury, dream interpretation—and a potent claim to divine favor, often backed by a storied pedigree. Their role encompassed purification rituals, healing, and the interpretation of all manner of signs. Civic leaders and generals went to great lengths to secure the services of renowned seers for critical ventures. Some seers, particularly those from famous lineages, amassed wealth and renown that echoed in Greek historiography and myth alike.

Unlike diviners in Babylonia or Assyria, who were typically bound to royal courts, Greek seers roamed city to city as “migrant charismatic specialists,” free to offer counsel wherever they were welcomed. Their fluid independence set them apart from priests—who tended local cults—and from chresmologoi, who recited written prophecies. At times, unscrupulous seers blended into the murky domain of magicians, feeding the comedic and philosophical critiques that survive in the plays of Aristophanes or the dialogues of Plato. Yet for every comedic portrayal of the seer as a trickster, abundant historical evidence shows that many Greek communities placed genuine trust in the mantis for guidance and protection.

Ultimately, the Greek seer’s success depended on consistently aligning human decisions with divine sanction. Whether leading armies to victory or curing the “madness” in a city, a good seer claimed a rare, privileged view into the supernatural. By skillful analysis of omens—and, arguably, by shaping those omens in times of need—they reassured leaders and citizens that the gods, when properly approached, would guide them to a favorable outcome. It was a powerful promise in a world that had few certainties and placed the workings of fate in the hands of the Olympian gods. Even centuries later, the memory of these venerable experts—and the families that nurtured them—remained part of the enduring tapestry of Greek religious thought.

In Summary, the ancient Greek mantis was far more than a simple fortune-teller. Combining hereditary lineage, a repertoire of divinatory techniques, and personal magnetism, seers occupied a singular niche in Greek society. From epic myth to historical warfare, they shaped outcomes both great and small, bridging mortal concerns and divine volition. Their story is one of adaptability, complexity, and unwavering cultural resonance—an integral element of ancient Greek religion that continues to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts of the classical world.

#Seers in Ancient Greece