The Black Death in France: Crosses on the Doors and a Kingdom in Crisis

From Marseilles to Bordeaux, Avignon to Paris, every corner of France in 1348–1349 bore witness to a catastrophe unlike anything known in living memory.

The Black Death that ravaged Europe in the mid-fourteenth century did not spare France. Following its onslaught in Italy, the plague crossed the Mediterranean, took hold in Marseilles, and proceeded to spread inland and along the coast with terrifying speed. In a matter of months, its lethal reach extended from the bustling papal city of Avignon to the winding streets of Paris, devastating rich and poor alike. Throughout France, as in much of Europe, daily life descended into chaos, hope dissolved into fear, and the search for answers—be it in spiritual or medical realms—gave way to desperation. Below, we trace the arrival of the plague in France, consider how political tensions shaped its impact, explore medieval medicine’s limited understanding of the disease, and examine how the plague turned life upside down in Paris and beyond.

The Plague Reaches Marseilles

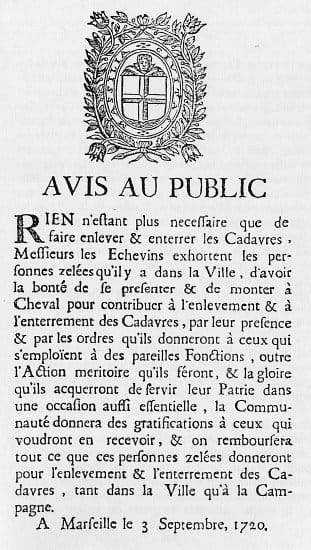

Shortly after the Black Death had begun its lethal work in Italy, it arrived in France via the bustling port of Marseilles. In January of 1348, several Genoese galleys—likely the same ones turned away from their Italian harbors—limped westward across the Mediterranean and docked in Marseilles. By this point, the crews were riddled with plague. Realizing the dire threat, local authorities reacted much like their Italian neighbors, driving the plague ships from port by any means available—burning arrows, quarantines, and outright refusal of entry. But their efforts came too late. The disease had already crept ashore.

Within just a few weeks, Marseilles exploded into chaos. Although contemporary figures often err on the side of exaggeration, chroniclers claim that 56,000 people died in the first month alone. The precise number may be impossible to verify, but the outbreak’s severity is clear. Both bubonic and pneumonic plague took root at once, rapidly infecting inhabitants in overcrowded neighborhoods with no effective barriers against the disease.

From Marseilles, the plague advanced along two primary routes. One headed west, striking Montpellier and Narbonne by February and March of 1348. It continued toward Carcassonne, Toulouse, Montauban, and eventually reached Bordeaux in August. The other route advanced north into the Rhône valley, reaching Avignon in March, seizing Lyons by the summer, and devastating Paris by June.

France on the Eve of Calamity

When the Black Death arrived, France was mired in significant internal and external strains. A longstanding rivalry with England had flared again, damaging French stability and leaving the peasantry burdened by war-related taxes and pillage.

A Kingdom at War

Tensions between King Philip VI of France and King Edward III of England had escalated over the latter’s continued rule of the Duchy of Guienne. Edward staked his own claim to the French throne, provoking immediate hostility from Philip. This dispute erupted into open warfare, culminating in the Battle of Sluys (1340) and then in the decisive English victory at Crécy (1346). Historians mark these events as the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War—a conflict that, while intermittent, would bleed the resources of both France and England for decades.

For ordinary French subjects, these hostilities spelled ruin. Soldiers—whether English invaders or French royal troops—plundered farmland, disrupted trade, and sowed terror. By the time plague arrived, much of the population was already exhausted from political and military strife. War’s chaos intensified the impact of a disease that thrived on fear, weakened bodies, and crowded living conditions.

A Perfect Storm

France, like many parts of Europe, had also suffered bouts of poor harvests and local famines in the years preceding the plague. Some areas faced skyrocketing grain prices; others endured persistent malnutrition that left people in a fragile state. In such an environment, the Black Death found fertile ground. Weakened by hunger, unsettled by conflict, and lacking cohesive leadership—despite Philip VI’s best efforts—French communities lacked the resilience to mount a united front against a mysterious, lethal contagion.

Avignon Under Siege

One of the most famous early flashpoints in France’s epidemic was Avignon, then home to the papacy. In 1309, Pope Clement V had moved the papal seat from Rome to Avignon, inaugurating a new era in which the popes lived and governed from what became a thriving city on the Rhône.

A Magnet for Disaster

Avignon’s prosperity and religious prominence drew enormous crowds of pilgrims. In normal times, these visiting faithful would enliven the city’s streets, support local businesses, and bring broader cultural exchange. But the very density that fueled Avignon’s growth in good years now turned lethal. Pilgrims, merchants, and church officials converged in crowded quarters, effectively amplifying the plague’s transmission among residents and newcomers.

Many contemporaries claimed that half of Avignon’s population died in the plague. Others put the death toll at over 120,000, though these figures are surely inflated. More reliable data come from the Rolls of the Apostolic Chamber, which show that 94 out of 450 members of the Papal Curia—over 20%—perished. If one in five of the wealthiest, best-provisioned churchmen succumbed, it stands to reason that the poorer majority, living in cramped conditions on inadequate diets, endured far higher rates of mortality.

Pope Clement VI’s Response

Pope Clement VI tried to survive, and help his flock survive, in ways that were both pragmatic and spiritual:

- Isolation: Clement secluded himself in his chambers. Legend says he sat between two large fires, believing it would cleanse the air. In reality, the fire likely drove away rats and fleas—the true carriers of plague—making this a rare effective (though accidental) measure.

- Flight to the Rhône Valley: Eventually, Clement withdrew to a castle outside Avignon, reasoning that by staying alive, he could serve the Church better than if he perished.

- Pastoral Reforms: The pope made absolution easier to obtain and initially encouraged processions in hopes of invoking divine mercy. Yet when these crowds risked spreading plague further, he abandoned public gatherings in favor of stricter isolation.

Despite Clement’s efforts, the Church faced enormous criticism. Many people believed that if God had sent the plague as punishment, why had the spiritual leaders not protected them? A sense of betrayal sometimes flared, leading to suspicion toward priests who failed to prevent or halt the disaster.

Medieval Medical Theories and the Church’s Influence

At the heart of fourteenth-century Europe lay a tangled web of religious ritual, fledgling science, and ancient medical doctrines. During the Black Death, these traditions collided head-on with a disease no one truly understood.

Priests Before Physicians

In medieval France, ecclesiastical authority dictated that if someone fell ill, the priest should be summoned first. Only once spiritual needs—such as confession, anointing, and prayers—had been addressed could a physician treat the patient. Under normal circumstances, this practice might be a mere inconvenience, but with the plague’s swift lethality, the delay cost many lives. By the time the priest finished prayers, the patient might have already died.

Both priests and doctors faced high mortality rates because of their proximity to the sick. Priests were expected to give last rites, while doctors explored remedies, however futile. Their devotion often came at the ultimate price.

The Church’s Role in Curbing Medical Research

Papal decrees and theological concerns also limited the expansion of medical knowledge. In 1300, Pope Boniface VIII issued a Bull forbidding the mutilation of corpses. Intended to curb grave-robbing and improper handling of remains, it had the unintended consequence of severely restricting autopsies and dissections. Surgical exploration and study of anatomy languished. Although some faculties—like Montpellier—practiced a form of dissection (one every two years), Paris actively avoided such pursuits. Reverence for Hippocrates and Galen further stifled innovation; medieval scholars hesitated to contradict these ancient authorities.

Explanations for the Plague

The medical theories that did prevail often stemmed more from cosmology than clinical observation:

- Astrological Alignments: The Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris famously blamed the plague on a conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars that occurred in Aquarius on March 20, 1345. Such alignments were traditionally viewed as harbingers of pestilence and disaster.

- Miasma Theory: Many believed the air itself was “poisoned,” drifting from place to place like a toxic fog. An array of speculative sources for this deadly atmosphere included rotting fish in the sea or decaying corpses left unburied after faraway wars.

- Humoral Imbalances: Sticking to Galenic medicine, physicians recommended attempts to purge “foul humours,” typically through bloodletting or strong emetics. Some even tried to lance or cut off buboes—an agonizing procedure that did little but spread infection.

Only a few—such as the Arab doctor Ibn Khâtimah—understood contagion. He noted how pneumonic plague, in particular, spread rapidly via breath and coughing, suspecting direct human-to-human transmission. His observations, though prescient, did not dominate mainstream medical advice in either Christian or Islamic territories.

Advice for Prevention

Lacking a true cure, fourteenth-century doctors recommended preventive measures to avoid “tainted air”:

- Isolation: Many suggested simply fleeing the city or shutting oneself indoors.

- Burning Scented Woods: Juniper, rosemary, ash, or vine were believed to purify the air; Pope Clement’s fires represent a variant on this theme.

- Quiet Living: Physicians advised minimal exertion to avoid stress, recommending a life of “calm conversation” and pleasant thoughts.

- Dietary Tips: Advice ranged from ingesting powdered emeralds to eating figs or fresh fruit. Arab authors recommended pomegranates, pickled onions, and plums. None of these had any proven effect on the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis.

Even if these measures sometimes worked—often by reducing contact with rodents or fleas—it was more happenstance than genuine scientific understanding.

Spreading North

By early summer of 1348, the Black Death reached Paris. A city known for its scholarly tradition, Paris was home to more physicians than anywhere else in Europe, yet neither advanced theory nor pious prayer spared its inhabitants.

Death Toll and Disruption

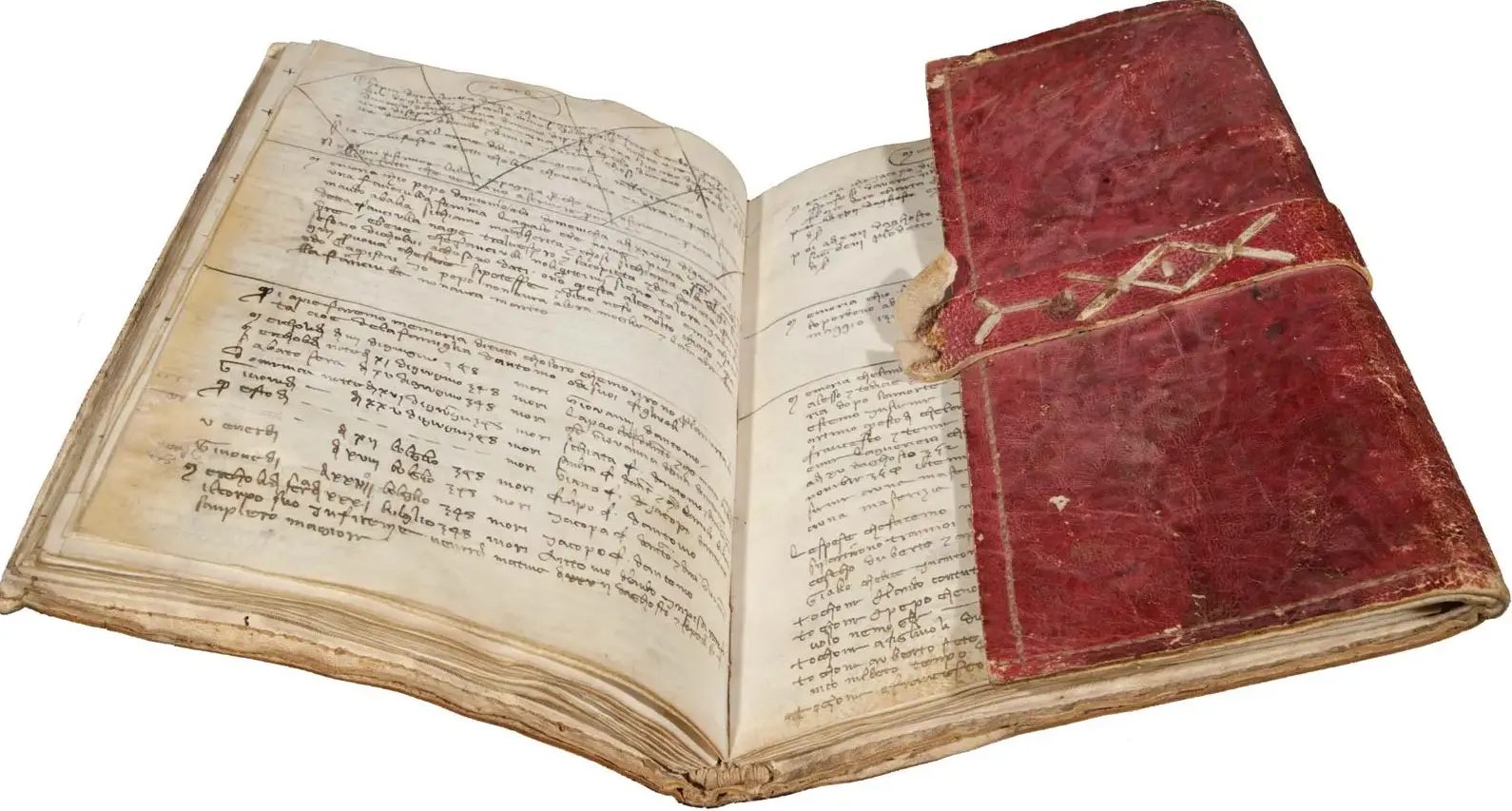

Donations and legacies left to the parish of Saint Germain l’Auxerrois, one of Paris’s largest parishes, provide a sobering snapshot. From Easter 1340 to mid-June 1348—before the plague arrived—there had been 78 bequests. In the nine months following the plague’s appearance, that number shot up to 419, nearly a six-fold surge.

William of Nangis, a chronicler of the period, describes a city overwhelmed:

“There was so great a mortality among people of both sexes… that it was hardly possible to bury them. In the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris… more than 500 corpses were carted daily to the churchyard of Saint Innocent…”

Whether that 500 figure is accurate or an exaggeration is unclear, but historians estimate that at least 50,000 Parisians may have died by early 1349. Such figures represent a significant fraction of a medieval city’s population.

Clergy, Courage, and Collapse

Much like in Avignon, many priests fled or simply died in the course of ministering to the sick. One exception was the “holy sisters” of the Hôtel-Dieu, who cared for plague victims at the risk of their own lives. William of Nangis lauds their courage and laments the high price they paid.

Meanwhile, ordinary Parisians reacted in varying ways:

- Debauchery and Despair: Some, convinced they had only days or weeks left, abandoned all restraint, engaging in wild drinking, dancing, and looting. The plague’s feverish convulsions merged with a broader dissolution of social norms.

- Flight and Isolation: The wealthy and noble families often fled to rural estates, hoping that distance from crowded districts might spare them. King Philip VI himself left Paris for Normandy, but the pestilence followed relentlessly.

In Normandy, entire villages were razed by disease or spontaneously abandoned. Chronicles record black flags flown at church spires as grim warnings to travelers that they approached plague-stricken sites, where rotting corpses lay unburied for lack of the living.

Royal Tragedies and a Burned Port

Bordeaux, a major southwestern port and significant site for English-French politics, was similarly hard-hit. The city already faced complicated allegiances—Edward III of England still held considerable authority there, and the Hundred Years’ War had turned Bordeaux into a strategic prize.

Princess Joan and the Château de l’Ombriere

Seeking to cement an alliance with Castile, Edward III arranged for his fifteen-year-old daughter, Princess Joan, to marry Prince Pedro of Castile. On the journey to Castile, Joan and her entourage stopped in Bordeaux, lodging in the Château de l’Ombriere. By August 1348, plague had overwhelmed the port district, and Joan’s chancellor, Robert Bourchier, died on August 20. The princess and her retinue, fully aware of the peril, tried to remain inside the château, hoping they could simply ride out the outbreak.

Tragically, it offered them no true protection. Princess Joan died on September 2. One of her courtiers, Andrew Ullford, fled to London to deliver the news to Edward III, arriving there by October 1. The King dispatched an envoy to retrieve Joan’s body. They found a city in chaos: Bordeaux’s mayor, Raymond de Bisquale, had burned the port area to the ground in a desperate attempt to stop the plague from spreading further. The fire raged out of control, destroying much of the port, including the Château de l’Ombriere. Joan’s remains were lost, leaving no royal body to return home for burial.

This tragic episode encapsulates how the plague nullified social status. Even royalty and their retinues, with access to safe lodging and high walls, could not escape the lethal disease infiltrating the streets below.

Conclusion

From Marseilles to Bordeaux, Avignon to Paris, every corner of France in 1348–1349 bore witness to a catastrophe unlike anything known in living memory. Homes were marked with crosses, black flags flew from church steeples, and entire villages burned or simply vanished from the map. While historians still debate the exact death toll, no region escaped untouched. For France—entrenched in the Hundred Years’ War, weakened by famine, and riven by internal dissension—the plague was a ruthless invader that transcended boundaries and shattered illusions of royal or papal protection.

In Avignon, Pope Clement VI’s scramble for spiritual authority amid widespread mortality reflected how religion and science alike struggled to offer answers. In Paris, the high concentration of doctors did little to stem the tide, as centuries-old beliefs in humoral imbalances and tainted air provided no real cures. Across the realm, lords and peasants alike discovered that neither fortress walls nor open countryside guaranteed safety.

Yet even as the Black Death consumed France, seeds of change emerged. Some communities took public health measures that would inspire future quarantine policies—Marseilles, for instance, would go on to establish more sophisticated plague controls in subsequent outbreaks. Rural depopulation and labor scarcity also set in motion subtle shifts in feudal relationships. On the cultural and intellectual front, the sheer scope of the plague forced a reckoning with long-held assumptions, slowly paving the way for new approaches to science, governance, and faith.

For medieval France, though, these transformations would arrive only after the worst of the crisis had passed. In the midst of the plague, with crosses chalked on doors and thousands dying in the streets, there was little sense of a potential renaissance. All that the living could do was bury the dead—when they had the strength to do so—pray for deliverance, and wait, terrified, for the pestilence to subside. When it finally did, those who survived would inherit a land shaken to its core, irrevocably changed by an invisible foe that knew no borders, social class, or creed.