The Pestilence Tyme: The Black Death in England

By 1350, the initial wave of the Black Death had largely burned through England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, leaving widespread emptiness and mourning in its wake

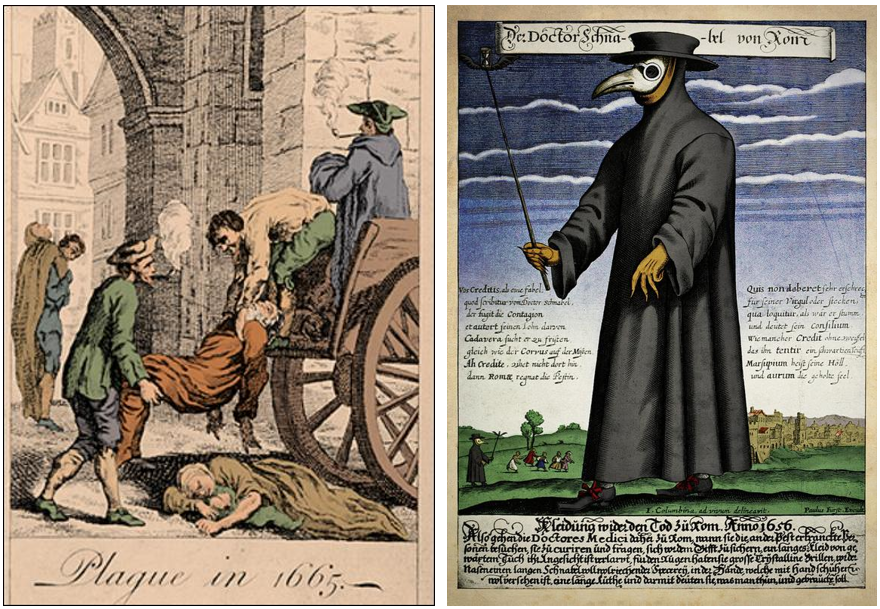

Throughout European history, few calamities can match the destruction wrought by the mid-fourteenth-century plague. This epidemic—popularly known as the Black Death—unleashed death, fear, and social disruption across the continent. In England, commonly referred to by chroniclers as the “Pestilence Tyme,” the toll was catastrophic. Paradoxically, however, England’s remarkably detailed ecclesiastical and manorial records also make it the place we know best about the plague’s day-by-day progress. What follows is a closer look at how the Black Death arrived on English shores, ravaged its towns, transformed its clergy, and spread to Wales, Scotland, and Ireland.

The Puzzle of Its Arrival: England’s Southern Ports

Despite the wealth of surviving documentation, historians still debate precisely where and when the Black Death first set foot in England. Many chroniclers single out Bristol, one of the country’s busiest ports, or Southampton as likely “entry points.” Yet a strong modern consensus identifies Melcombe Regis (now part of Weymouth in Dorset) as ground zero.

By 1348, Melcombe was a thriving harbor that had contributed as many ships to Edward III’s siege of Calais as London or Bristol. Its traffic with France and the Channel Islands was near-daily, leaving it vulnerable to arriving vessels already harboring plague. The Grey Friars’ Chronicle adds that a fateful ship, originally from Bristol, docked in Melcombe; once it spread infection there, it sailed on to Bristol, sowing pestilence a second time.

Chroniclers also disagree on the plague’s precise arrival date—some claim midsummer 1348, others as late as Christmas. The Bishop of Bath and Wells issued a directive on August 17 calling for Friday processions and prayers against a pestilence ravaging the “neighboring kingdom,” which might mean France but could also imply southwestern England. Regardless of the precise date, by October 1348, Dorset’s ecclesiastical records reveal that priests were dying rapidly. Shaftesbury alone replaced its vicar four times between late November and early January 1349, a sign that the disease had erupted with shocking force.

At the time, England was relatively prosperous under Edward III. The wool and cloth industries boomed, and about 85-90% of the population lived in rural villages, which would soon become the front line of plague’s devastation. Indeed, some communities vanished entirely.

Clerical Casualties and Religious Response

The structure of medieval society made priests pivotal during epidemics: faithful Catholics needed confession and last rites, and it was the clergy who fulfilled these tasks at great personal risk. Ecclesiastical records—like the Books of Institution—therefore offer a keen lens on how heavily the Black Death struck.

In Dorset, new vicars were being instituted at a frantic pace. Meanwhile, the Bishop of Bath and Wells tried to rally the faithful by issuing calls for prayer, but by early 1349, he faced grim reality: priests were dying faster than they could be replaced, or refusing to serve in plague-ridden parishes. The bishop granted special permissions for people to confess sins to whomever would listen—even a layperson or a woman—if no priest could be found. Such a remarkable concession underscores how desperate the Church had become.

Church leaders also contended with morale issues. As in many corners of Europe, some clergymen simply abandoned their flocks, fleeing to safer regions or refusing to visit the sick. Others, however, stayed and labored heroically until they, too, succumbed. The chaotic scramble to fill clerical vacancies would have lasting repercussions on the church’s moral standing and competence for generations.

Through the West Country: A Swift Spread

From Dorset, the plague fanned out unpredictably but relentlessly. It hit Bristol so quickly that it suggests multiple points of entry by sea. By year’s end (1348), nearly every village in southwest England had felt its wrath. City councils took desperate measures: Gloucester sought to quarantine itself from Bristol entirely—banning traffic or goods from the decimated port. However, isolation efforts failed.

In just six months, 80 parishes in Gloucester lost their priests. Local records mention frantic efforts to fill benefices. In certain cases, a single parish might cycle through multiple rectors within mere months. Over the winter of 1348-1349, the plague advanced across Wiltshire, Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex, Kent, and East Anglia. Some places caught it via overland routes from other infected towns; other communities likely became infected by ships arriving in local harbors. By early 1349, half of England seemed beset by plague from multiple directions at once.

Calamity in the Countryside

While large ports were visibly hit first, the countryside bore equally grim losses. In Oxford, at least 35% of the clergy died. Eynsham Abbey, just a few miles from the city, became a symbolic microcosm of the crisis. Its abbot, Nicholas, was deposed for an unspecified offense; two administrators were appointed to govern the monastery in his stead, but within weeks both had died. The two monks sent to replace them also perished en route. With no one left to administer Eynsham, Bishop Gynewell reinstated Nicholas.

Local manorial rolls record even bleaker stories. In the villages on Eynsham land, entire communities disappeared. Tilgarsley, once a prosperous settlement, was abandoned to weeds. In Woodeaton, all but two of the villagers died. Seeing economic opportunity in crisis, Abbot Nicholas replaced the dead tenants with new arrivals who paid slightly higher rents but owed fewer feudal services—a glimpse of the radical transformations in land arrangements that would follow the Black Death.

Cuxham, near Thame, famously illustrates how plague decimated local leadership. From 1288 to 1349, only two men served as reeve (an official who managed the manor’s accounts). But during the plague, reeves died in quick succession: one lasted a month, another just a few weeks, another a mere year. A parade of grim replacements underscored how daily governance collapsed under the pestilence’s assault.

From Wycombe to Winchester, the figures are devastating. Certain parishes recorded clerical mortality rates approaching 50-60%. Usually, historians infer that such high death rates for priests likely mirrored or exceeded those among the general population, since the clergy’s duties placed them in direct proximity with the sick and dying.

The Great Mortality in London

Although the plague struck hardest at scattered villages, England’s most populous city offered no safety. London in the mid-fourteenth century had an estimated 70,000–75,000 residents crammed into roughly two square miles. Overcrowding, limited sanitation, and constant traffic from river trade created a perfect breeding ground for contagion.

Overcrowded, Unsanitary Streets

Medieval Londoners lived closely packed, with narrow lanes, animal pens, and open sewers. Waste of all kinds often landed in the street—sometimes draining into gutters, often clogging them—and eventually washed into communal cesspits or the Thames. Water supplies became contaminated when these cesspits seeped into wells. Ditches like the Fleet Prison Ditch served simultaneously as sewage outflows and moats, accumulating so much waste that the River Fleet’s flow was routinely obstructed.

Butchers added to the filth, discarding entrails into the Thames. St. Nicholas Shambles, near the Fleet, was so fetid by the mid-1300s that the king forced the butchers to move outside the walls. Such conditions did not “cause” bubonic plague per se—rat fleas carried the bacterium Yersinia pestis—but malnourishment and diseases like dysentery weakened immune systems, giving the plague deadly leverage.

Bodies Filling Mass Graves

The plague likely reached London in late 1348, either through refugees fleeing infected shires or from cargo vessels sailing into the port. By early 1349, the city’s existing graveyards overflowed, prompting swift creation of new burial grounds at Smithfield and Charterhouse. Corpses piled five or six deep, separated by thin layers of soil. Chronicler Robert of Avesbury claimed 200 burials a day, though estimates varied wildly. Later commentators, like John Stow, erroneously suggested 50,000 bodies in Charterhouse alone—a figure exceeding London’s entire adult population. More likely, at least one-third of Londoners perished, something close to 25,000–30,000 souls.

Neither wealth nor status guaranteed survival. Archbishop of Canterbury John Stratford died in August 1348, followed by his successor, John Offord, who perished in May 1349 before he could even be enthroned. A third successor, Thomas Bradwardine, died that August soon after returning from Avignon. Meanwhile, the royal surgeon Roger de Heyton succumbed in May, and numerous prominent abbots and guild wardens died by year’s end.

Sweeping East Anglia and the North

With London consumed, plague spread into East Anglia. Norwich, second only to London in size, may have lost more than half its inhabitants. Diocesan records show that the typical annual rate of priestly “institutions” stood around 80, but between March 1349 and March 1350, 831 new clergymen were appointed in the Norwich diocese—over ten times the norm. Neighboring Ely saw similarly staggering appointments.

As the plague traveled north, it exposed its unpredictability. Some areas—Cambridgeshire villages like Oakington or Dry Drayton—lost between 50% and 70% of the population, while other nearby manors emerged relatively unscathed. Lincolnshire endured brutal losses: 15 of its villages were said to be wholly emptied. Northamptonshire, in contrast, survived with only modest fatalities.

Nevertheless, local administration often managed to function. In York, an inquest convened on August 7, 1349, to examine the death of one William Needler, concluding it was from plague and not foul play. This bizarre normality—an inquest in the midst of mass death—indicates that communities tried to maintain some structure despite the chaos.

However, further north, in the aftermath of Scottish raids, administrative records are much sparser. In Carlisle, farmland near the castle went untended for 18 months due to lack of labor. Durham saw entire villages vanish: West Thickley’s population was annihilated, and the official note read, “they are all dead.” A local rumor described a peasant who, having lost his entire family, wandered the roads searching for them for years, driven mad by grief.

Wales, Scotland, and Ireland

Welsh Ports and Valleys

The plague’s arrival in Wales probably followed soon after it reached Bristol and Gloucestershire; some believe it simply drifted over the River Severn into Monmouthshire. By March 1349, Abergavenny was decimated. Nearby counties recorded up to 90% of tenants missing or dead. In Cardigan, 104 tenants were reduced to a mere 7 by June.

Northern Wales is less documented, but what few hints survive suggest extreme devastation. Holywell’s miners disappeared; those who survived refused to return to dangerous shafts. The Welsh poet Jeuan Gethin, writing that spring, vividly described plague as a “rootless phantom” and “black smoke,” the buboes a “grievous ornament” erupting at terrifying speed.

Scotland’s Ill-Fated Invasion

If Henry Knighton’s chronicle is accurate, the Scots tried to exploit England’s crisis by launching an invasion from the forest of Selkirk. Tragically, plague broke out among Scottish troops, who fled back to their homes, unwittingly carrying the disease into Scotland. Hard data on mortality remain slim, but John of Fordun recorded that “nearly a third of mankind” had died. Compared to other medieval chroniclers, that estimate is soberingly moderate. Modern historians concur that around one-third of Britain’s entire population likely died—making Fordun’s figure possibly close to the truth.

Ireland’s Late Awakening

Meanwhile, Ireland long remained unscathed. In August 1349, Richard Fitzralph, Archbishop of Armagh, told Pope Clement VI at Avignon that the plague was devastating England but had yet to trouble Scotland or Ireland significantly. However, unknown to him, the disease had already reached Irish shores. The Archbishop of Dublin died in mid-July, the Bishop of Meath by the end of that month. By autumn, many localities were reeling. Ireland, like Wales, had been weakened by English invasions and periodic civil war. Now, plague seemed like the final blow.

The Kilkenny Chronicle, penned by Friar John Clyn, conveys the unimaginable suffering. Clyn wrote how plague “stripped villages, towns, and castles,” with priests and confessors dying together “so that penitent and confessor were carried to the grave at once.” Clyn’s final pages reflect acute despair:

“And I, Brother John Clyn... waiting for death to visit me, have put into writing truthfully all the things that I have heard... And, lest the writing should perish with the writer... I leave parchments to continue this work, if perchance any man survive and any of the race of Adam escape this pestilence.”

Another scribe simply added “great dearth” beneath Clyn’s account, and concluded, “Here it seems that the author died.”

Lasting Effects and Somber Lessons

By 1350, the initial wave of the Black Death had largely burned through England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, leaving widespread emptiness and mourning in its wake. Chroniclers usually wrote in stunned, biblical language, struggling to capture the horror. Vast farmland lay vacant for years, workforce shortages forced landowners to offer higher wages or lower feudal obligations, and the mass replacement of priests accelerated tension within the Church.

These transformations—far-reaching and often disruptive—foreshadowed even bigger shifts in the social and economic spheres. Over the next decades, laborers would gain leverage, landholdings would change hands on a scale previously unimaginable, and the seeds of discontent with ecclesiastical hierarchy would germinate into larger reforms. Even so, for many medieval observers, the plague was simply a cataclysm that showed “the whole world... placed within the grasp of Satan,” as Brother Clyn so hauntingly put it.

The Pestilence Tyme in England, as it came to be called, was at once a tragedy and a turning point. When the Black Death receded—having claimed perhaps one-third to one-half of the population—its survivors inherited a wounded realm. The fields, cities, churches, and ports that had fueled English prosperity lay half-empty, their old social order cracked at the foundations. Yet they also held the faint stirrings of rebirth. Over time, new forms of tenancy, new relationships between laborers and landowners, and new religious pressures would reshape England’s direction. In the end, though, the stories that remain to us—through the records of priests who died at the altar, abbots vainly replaced by half a dozen equally doomed caretakers, or entire manors emptied overnight—stand as a testament to the darkest days in medieval memory.

The Pestilence Tyme was a searing reminder that no class or region, no city or village, was safe from the invisible threat. And while centuries have passed since that first wave of the plague, the stark echoes of deserted fields, scrawled last words, and mass graves remain a cautionary tale of how society responds—and fails to respond—when faced with an overwhelming and mysterious catastrophe.