The Art of the Consultation and Divination with the Seers

The art of the consultation in ancient Greece was never a simple question of “right or wrong” omens

In ancient Greece, professional seers occupied a respected yet complex position in society. Responsible for interpreting the will of the gods through signs—most commonly the entrails of sacrificial animals—they performed a vital function in helping individuals and communities make critical decisions. From military campaigns to private affairs, Greeks often sought divine counsel through these experts. This post explores the ritual, performative, and intellectual dimensions of the seer’s craft, drawing on historical episodes from Xenophon’s Anabasis, examples from Greek tragedy, and comparative anthropological insights.

Below, we will examine how consultations typically took place, what made them succeed (or fail), and how seers’ roles extended beyond mere ritual actions into nuanced performances with significant social influence. We will also observe how Greek seers, while often portrayed as vessels of divine knowledge, relied on their own intelligence, creativity, and understanding of social context to guide their clients—and secure their own reputation.

Learn the art of seers in Ancient Greek

The Seer’s Ritual Role

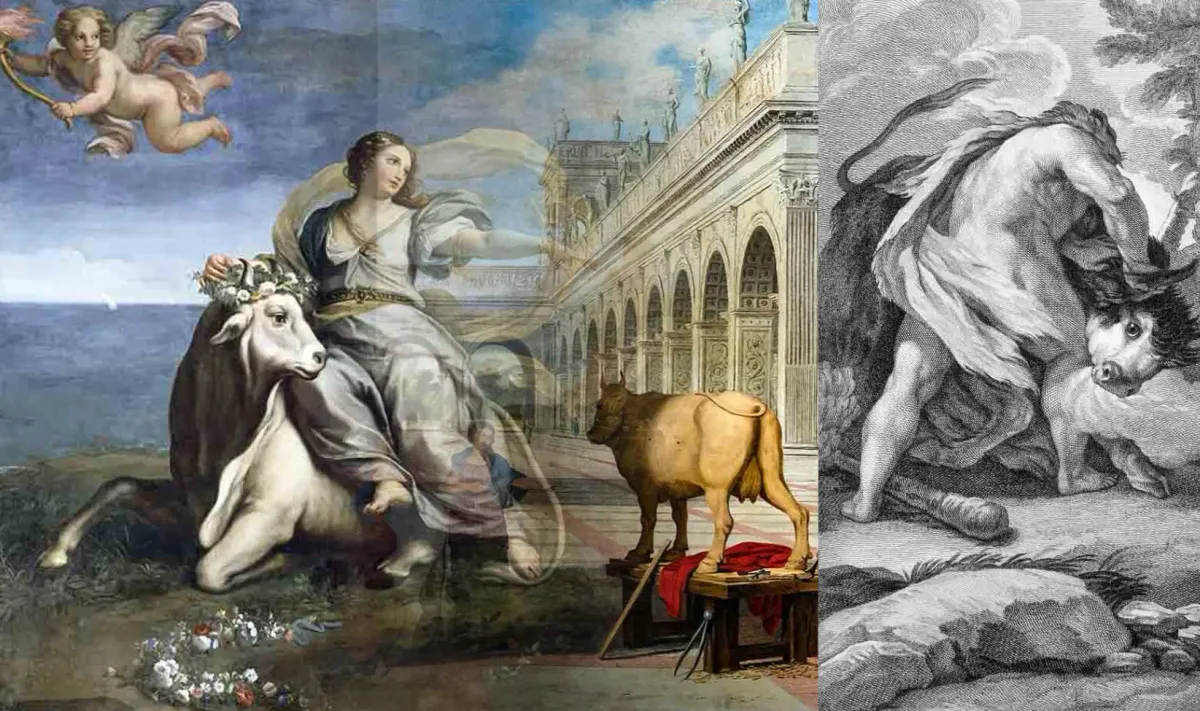

A seer in ancient Greece generally began each divinatory session by preparing a sacrifice in a carefully prescribed manner. Dressed in a white tunic and adorned with a garland, the seer would position one or more sacrificial victims—often sheep, goats, or other animals—near an altar. Addressing a particular deity, such as Zeus the King or Heracles the Leader, the seer would utter a formal prayer and then slaughter the victim. The heart of this process involved examining the entrails, especially the liver. The Greeks believed that the gods inscribed messages onto the organs, and it was the seer’s skill to “read” and interpret these divine signs.

Because no vast libraries of standard omen-collections like those found in the ancient Near East seem to have existed in classical Greece, training for seers took place through apprenticeship to more experienced practitioners. Later on, some written materials on the art of extispicy may have circulated, but knowledge was largely transmitted orally. While this might sound subjective or imprecise, unwritten symbolic systems can be highly intricate and reliable to insiders. The Greek seer’s capacity to read subtle markings on the liver or other entrails was therefore neither random nor haphazard, but grounded in an established—if orally preserved—body of knowledge.

Divination as Performance

Divination in Greece was as much a public performance as it was a religious ritual. Seers were often commissioned by individuals of high status—such as generals or statesmen—who needed to persuade both the gods and human observers that their course of action enjoyed divine sanction. Public sacrifices drew onlookers, including the clients themselves and often members of the community. Consequently, the seer’s interpretive prowess was not only in reading signs from the gods but also in displaying competence, authority, and confidence before an audience.

Anthropological studies of ritual have shown that public ceremonies tend to exhibit highly formalized, theatrical elements. The seer’s prayers, gestures, and solemn treatment of the sacrificial victim all contributed to an atmosphere that reinforced the impression of being in communication with the divine. A successful performance could bring a seer fame, material rewards, and prestige, while failure or errors in prediction could undermine a seer’s standing.

Intelligence, Creativity, and Flexibility

Despite the highly ritualized aspect of extispicy, a seer still needed to be flexible and creative. Competition among seers was not uncommon. Some might rely more on reading the subtle cues of a client’s needs and worries, while others might emphasize their innate prophetic abilities or special skills.

Crucially, being a self-aware performer did not necessarily mean a seer was insincere or manipulative. In fact, sincerity and showmanship could coexist. Anthropological parallels with shamans in various societies demonstrate that even those who consciously employ theatrical elements may still fully believe in the powers and messages they convey. If a seer was perceived as cynically tailoring his predictions for personal gain, he would risk losing credibility. The tension between understanding a client’s social context and maintaining fidelity to the craft was, therefore, a balancing act requiring both intelligence and genuine belief.

Greek Society’s Expectation of Expertise

Ancient Greece was a culture that prized and publicly tested expertise. Physicians competed for prestige and clientele, frequently performing in front of patients, families, and rivals. Seers likewise found themselves on display, needing to prove their abilities repeatedly—sometimes under adverse or high-stakes conditions. Delivering accurate or at least trusted readings was the surest route to prominence.

Given that many divinatory rituals took place before audiences, the seer’s reputation rested on performing competently and persuasively. A successful reading was one that not only matched the actual outcome but also fit the social needs and expectations of the client. Over the longer term, building a track record of “getting it right” reinforced confidence in the seer’s skills and thus ensured continued patronage.

Case Studies from Xenophon’s Anabasis

Xenophon’s writings are perhaps our most valuable historical source regarding how seers operated in real-life scenarios. He depicts multiple interactions between seers and clients—often himself—and in so doing, reveals the complexities of the consultation process.

The Story of Silanus the Ambraciot Seer

In one instance (Anabasis 1.7.18), Cyrus the Younger was preparing for battle against the Persian King. The seer Silanus performed sacrifices and told Cyrus he would not face battle for at least ten days. Cyrus, relieved by the news, promised Silanus ten talents (an enormous sum) should this prediction prove correct. As it happened, the King indeed did not appear within that time. Cyrus kept his word, making Silanus a wealthy man.

This episode shows that seers sometimes took calculated risks. Silanus may have recognized, strategically, that the Persian King was unlikely to strike immediately. His prediction could be framed both as divinely inspired and based on an understanding of military realities. If he had been wrong, he might have lost face. Being a seer thus involved an acute awareness of situational dynamics as well as skill in interpreting the gods’ messages.

Divination and Conflict of Interests: Silanus Again

Later in the Anabasis (5.6.15–19, 28–30), Xenophon decided to sacrifice privately about the possibility of founding a colony near Sinope. He asked Silanus to perform these sacrifices because Silanus was an experienced professional. However, Silanus intentionally leaked Xenophon’s plan to the soldiers, stirring up controversy. Why not simply lie in his interpretation of the sacrificial omens, telling Xenophon the gods disapproved? According to Xenophon, Silanus knew that Xenophon was knowledgeable enough about divination to check his work. Lying about the entrails would be risky; too obvious a manipulation could destroy the seer’s credibility. Instead, Silanus subverted Xenophon’s plans through rumor-mongering rather than false prophecy.

This episode underlines how the seer’s role was less about “inventing” signs than about interpreting them in a way that both matched the situation and preserved trust. Even if the seer had ulterior motives, a blatant misreading of the entrails could easily backfire.

The Seer Eucleides and the Importance of Social Context

One of the most revealing encounters appears near the end of the Anabasis (7.8.1–6). There, Xenophon meets Eucleides, a seer from his hometown, who initially assumes Xenophon has grown rich from his campaigns. Upon learning Xenophon is nearly penniless, Eucleides carefully examines sacrificial omens and concludes that Xenophon’s ongoing misfortune stems from failing to sacrifice to Zeus Meilichios (the aspect of Zeus who receives propitiatory sacrifices). Notably, Eucleides knew Xenophon had regularly offered these sacrifices at home. This social knowledge helped the seer craft the best interpretation.

Right after Xenophon performs the requisite sacrifice to Zeus Meilichios, better fortune follows: he recovers a beloved horse and gains new resources. Xenophon presents this as proof that the gods, through the seer, corrected the oversight. It is also evidence of a healthy relationship between seer and client, in which the seer’s understanding of the client’s social and religious background allows a meaningful—and accurate—interpretation.

Negotiation, Social Knowledge, and the Seer-Client Relationship

A seer’s advice, whether on the battlefield or in private life, was rarely limited to a simple “yes” or “no” about omens. Because omens had to be interpreted in context, the seer needed to draw out details of the client’s predicament and environment. The discipline of anthropology highlights how diviners construct answers relevant to each client’s “typical problems and solutions.” In ancient Greece, examples abound:

- Military Campaigns: A seer would need to know the general’s strategic aims and the morale of the troops before indicating whether the gods favored an advance or recommended caution.

- Private Affairs: Seers advising on marriages, property purchases, or business ventures relied on familiarity with the client’s family situation and personal anxieties.

Such an approach is less about “manipulating” signs and more about making them meaningful. Divination is a conversation as much as a ritual. Through repeated queries, clarifications, and adjustments, the seer and client arrive at an agreed-upon interpretation and plan of action. In many ways, the success of the reading depended on how well the seer could integrate religious signs with an understanding of human concerns.

When Consultation Breaks Down: Homer and Tragedy

Not all consultations proceeded smoothly. In Homeric epics and Greek tragedies, there are notable clashes between seers and those seeking (or forced to hear) their counsel. These fictional or legendary episodes provide an “inverse” picture that underscores what happens when mutual trust collapses.

Homer’s Iliad: Agamemnon and Calchas

In Iliad Book 1, the Achaeans suffer a plague. Calchas, the seer, explains the plague is Apollo’s punishment for Agamemnon’s mistreatment of Chryses (a priest of Apollo). Furious at hearing bad news, Agamemnon insults Calchas for “always prophesying evil.” Yet, ironically, he also recognizes that the seer’s words may be right and eventually returns the captive girl to assuage Apollo’s wrath. Here, the tension lies in the messenger becoming a target of blame, even while his message leads to a correct resolution of the crisis.

Sophocles: Teiresias in Oedipus Tyrannus and Antigone

Teiresias is the quintessential tragic seer. In Oedipus Tyrannus, Oedipus’s initial respect for Teiresias deteriorates into hostility the moment Teiresias delivers the unwelcome news that Oedipus himself is the murderer he seeks. Their interaction becomes an argumentative confrontation rather than a reasoned consultation.

A similar breakdown occurs in Antigone: Creon initially respects Teiresias but accuses him of being corrupt when the seer warns that Creon’s actions displease the gods. Only after Teiresias leaves angrily does Creon reluctantly comply with the seer’s advice—too late to avert tragedy. These dramatic portrayals reverse what should be a collaborative, trust-based process. By highlighting extreme distrust and anger, tragedy explores the dire consequences of ignoring or attacking the messenger.

Euripides: Bacchae

In the Bacchae, King Pentheus confronts the seer Teiresias, accusing him of promoting the worship of the new god Dionysus purely for profit. This time, Teiresias responds with a largely “rational” or “theological” argument, rather than offering specific oracular instructions. While it’s still a conflict, it shows another mode: a seer who uses reasoning to support a religious viewpoint, beyond simply reading omens.

The Seer’s Compassion and Close Advisement

In contrast to the tragic conflicts, there are glimpses of seers acting kindly and protectively toward their clients. In Sophocles’ Ajax, the seer Calchas privately warns Ajax’s half-brother, Teucer, to keep Ajax from leaving his tent on a particular day—indicating the seer’s genuine concern. This compassionate approach suggests that in normal circumstances, seers often gave advice that aligned with a client’s best interests.

Another prime example is Xenophon’s relationship with Eucleides. The seer approached him with empathy, saw Xenophon’s distress about finances, and identified a religious omission that supposedly caused it. The subsequent sacrificial ritual brought about a resolution, demonstrating how crucial trust was between seer and client. A seer who understood personal details could offer practical solutions, bridging the gap between divine signs and everyday problems.

Performing Under Pressure: The Calpe Harbor Incident

One of the more dramatic cases described by Xenophon involves the seer Arexion during the Greek army’s stay at Calpe harbor (Anabasis 6.4.12—5.2). With supplies dwindling, Arexion’s sacrifices indicated it was not favorable for the army to depart. Many soldiers suspected that Arexion and Xenophon were conspiring to keep them there—perhaps even to found a new colony. To dispel these suspicions, Xenophon invited any other seers present in the army to observe the sacrifices. Still, the omens remained unfavorable, incensing the hungry troops.

Finally, on the fourth day, after a secure camp was built and provisions arrived, the omens at last proved favorable. Arexion witnessed an auspicious eagle and commanded Xenophon to lead the way. From Xenophon’s perspective, it was not “manipulation” but divine guidance aligning with a changed strategic reality. To the modern eye, it may seem suspiciously convenient that the omens improved just as conditions did. However, for Xenophon—and likely for many Greeks—this was precisely how the gods showed their will in a dynamic, evolving context. The seer’s skill lay not in fraud but in consistently and convincingly reading signs.

Conclusion: Why the Seer Mattered

The art of the consultation in ancient Greece was never a simple question of “right or wrong” omens. Rather, it involved three key aspects:

- Ritual Expertise: The seer followed a prescribed sequence of sacrifices, prayers, and interpretive techniques, lending religious legitimacy to the consultation.

- Performance and Persuasion: Public ritual demanded that a seer project competence, confidence, and sincerity, even under tense or uncertain circumstances.

- Social and Intellectual Engagement: To provide a useful interpretation, a seer had to know the client’s situation—whether that client was a general planning a campaign or a private individual facing personal dilemmas.

Historical narratives like Xenophon’s Anabasis show that cooperation between seer and client depended on shared trust and thorough social knowledge. When clients suspected manipulation or disliked the messages they received, the entire process could disintegrate, as in the tragic conflicts between Teiresias and proud rulers like Oedipus or Creon. But when trust endured, the seer’s guidance could restore order, avert calamity, or legitimize decisions.

This delicate interplay of ritual, performance, intelligence, and collaboration made the seer’s role indispensable in many spheres of Greek life. Far from being mere soothsayers mouthing platitudes, seers were cultural brokers. They connected the mortal realm with the divine, facilitated cooperation among political leaders and their communities, and offered insight into pressing, practical concerns. Their success was measured not just by whether events bore out their pronouncements, but by how well they integrated those pronouncements into the client’s social reality.

In the modern imagination, ancient seers might appear manipulative or superstitious. Yet, the evidence suggests that many were sincerely devoted to their craft. They had personal stakes in pleasing both the gods and their human patrons, and success demanded a finely tuned awareness of social and psychological contexts. Whether read as historical record or dramatized in myth and tragedy, the stories of Greek seers underline how divination, negotiation, and personal rapport shaped individual choices and communal destiny in the ancient world.