Thanatos: The Silent Hand of Death

Despite his seemingly unyielding nature, Thanatos wasn't immune to trickery

Thanatos, the Greek god of death, remains a shadowy figure compared to his brother Hypnos, the god of sleep, or Hades, the ruler of the underworld. Yet, his presence permeates Greek mythology, subtly shaping narratives of mortality and fate. From ancient poetry to modern canvases and even comic books, the influence of this minor deity continues to resonate. This exploration delves into Thanatos's origins, his role in Greek literature, and his surprising afterlife in modern culture.

Origins and Family

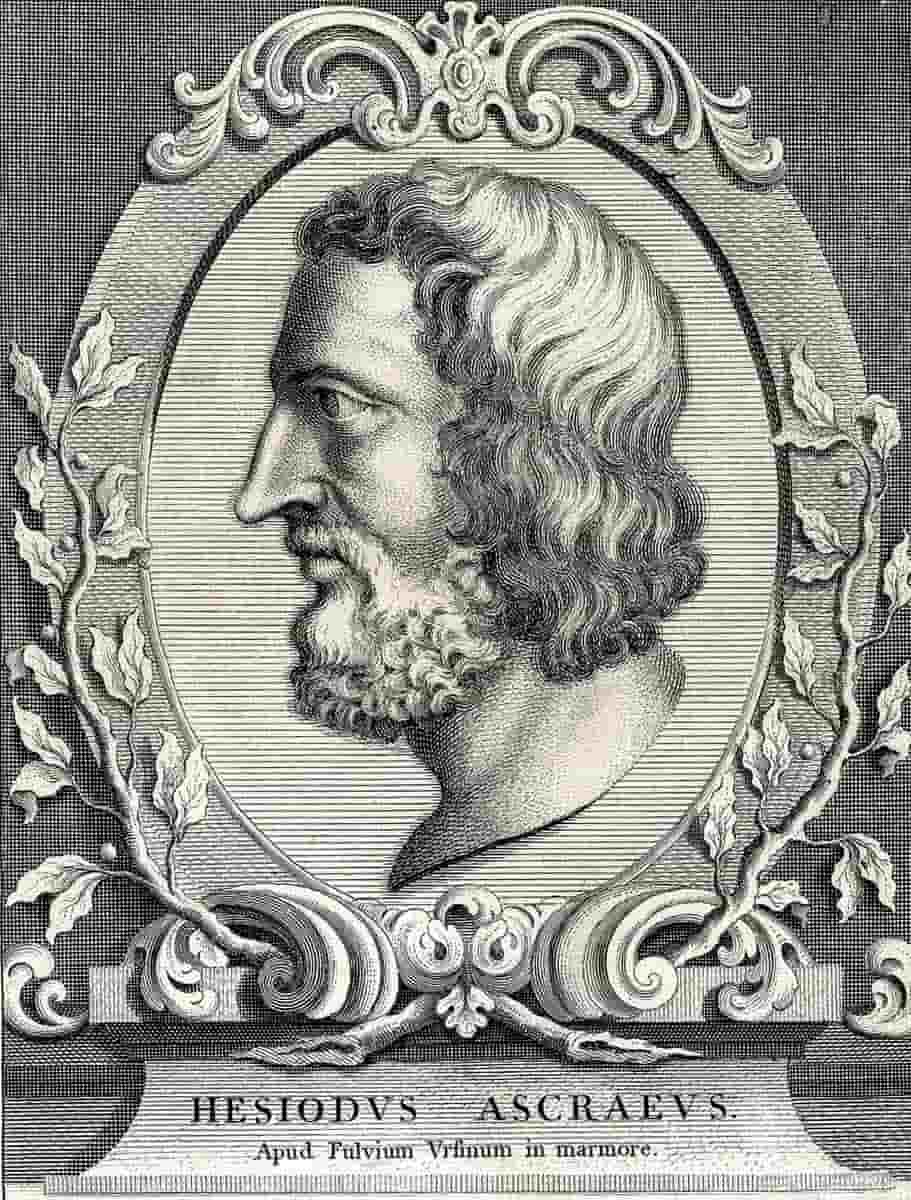

Thanatos's lack of widespread recognition might stem from his less illustrious parentage compared to Hades, whose brothers were the mighty Zeus and Poseidon. Hesiod's Theogony, an 8th-century BCE poem detailing the genealogy of the gods, reveals Thanatos as the son of Nyx, the goddess of Night, and the brother of Hypnos. This parentage places him firmly within a realm of darkness and inevitability. Hesiod's portrayal paints a chilling image of Thanatos: unloved by gods, possessing a heart of iron and a pitiless spirit, his grasp inescapable.

He is described as having an immutable spirit, a heart of iron, and being unloved even by the gods. His siblings include equally grim personifications such as Geras (Old Age), Oizys (Suffering), Moros (Doom), and Nemesis (Retribution). This morbid family reinforces Thanatos's association with the darker aspects of existence. It's important to note, however, that Thanatos wasn't solely responsible for all deaths.

While he presided over peaceful deaths, the violent ends met by many, especially on the battlefield, were often attributed to the Keres, bloodthirsty female spirits of death. His close association with the Fates, daughters of Nyx, further underscores his connection to destiny, specifically with Atropos, the Fate who cuts the thread of life.

The Cunning of Sisyphus

Despite his seemingly unyielding nature, Thanatos wasn't immune to trickery. The cunning King Sisyphus famously outsmarted him not once, but twice. The first instance saw Sisyphus, punished for betraying a divine secret, tricking Thanatos into demonstrating the chains of Tartarus, trapping the death god and causing chaos on earth. Ares, the god of war, frustrated by the futility of battles without death, forced Thanatos's release.

The second time, Sisyphus, having escaped the underworld, convinced Persephone he hadn't received a proper burial. Upon returning to the land of the living, he refused to return to the realm of the dead, prompting Hermes to drag him back to Tartarus, where he was condemned to eternally roll a boulder uphill, only to have it tumble back down each time he neared the summit. This tale, recounted in a fragment by the 6th-century BCE poet Alcaeus, demonstrates that even death could be temporarily outmaneuvered by human ingenuity.

Thanatos in Literature

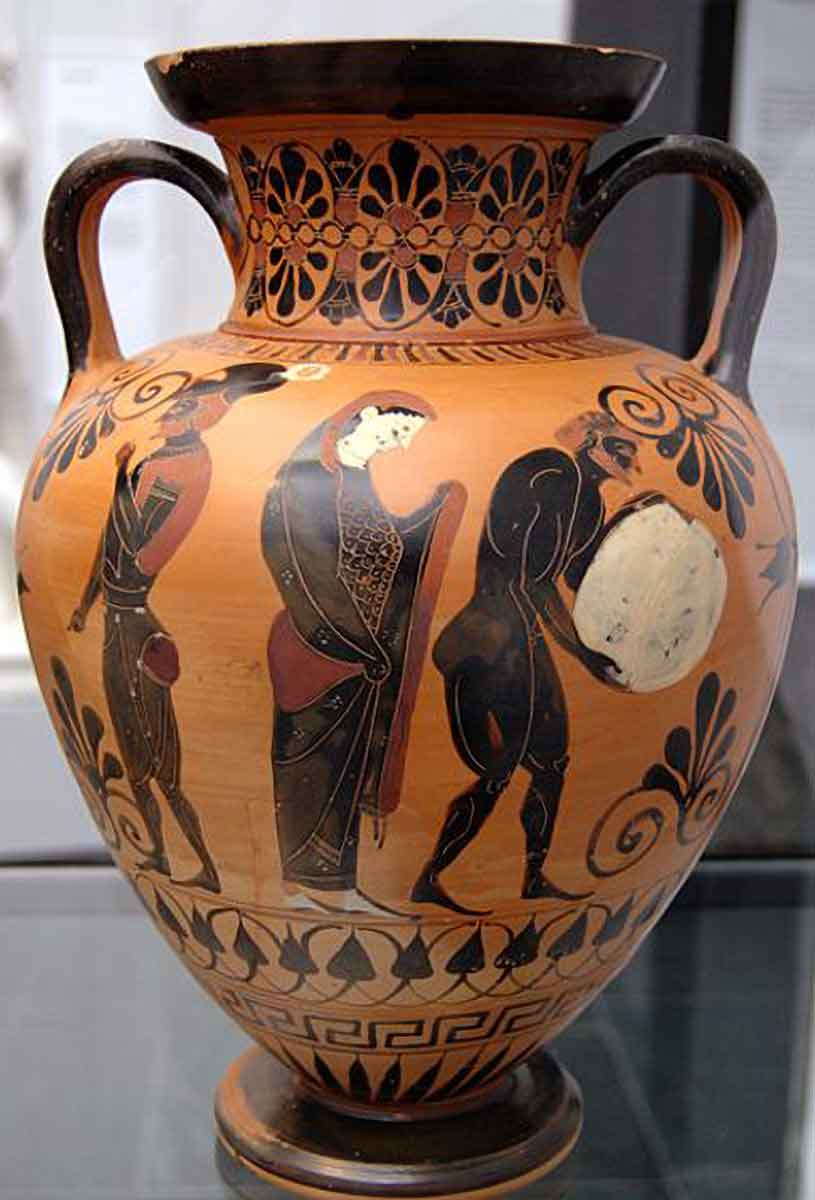

Thanatos’s appearances in Greek literature, while not always central, are significant. In Homer’s Iliad, he and Hypnos are tasked by Zeus with carrying the fallen hero Sarpedon back to his Lycian homeland, a moment of poignant respect amidst the brutality of war. Euripides's Alcestis, a play blurring the lines between tragedy and comedy, offers a more dramatic portrayal.

Queen Alcestis sacrifices herself so that her husband, King Admetus, may live. Herakles, visiting Admetus, learns of this sacrifice and, in gratitude for the king's hospitality, wrestles Thanatos, overpowering him and returning Alcestis to life. This episode showcases Thanatos as a force that can be confronted, even defeated, by extraordinary strength and devotion.

Thanatosis: Playing Dead

The word “Thanatos” extends beyond the figure of the death god, influencing language and understanding of animal behavior. "Thanatosis," derived from the same Greek root (meaning "I die"), refers to the phenomenon of "playing dead." Animals feign death to deter predators or, in some cases, to lure prey closer.

The opossum is perhaps the most famous practitioner of this tactic, leading to the idiom "playing possum," meaning to feign ignorance or death. This etymological connection highlights how the ancient Greek god's name has entered modern language, subtly linking human behavior to the natural world's strategies for survival.

Thanatos in Modern Culture

Despite his relatively minor status in the pantheon, Thanatos continues to exert a surprising influence on modern culture. His image appeared on Roman coins minted in Thrace and Moesia, paired, fittingly, with emperors known for their ruthlessness. More recently, he entered the realm of psychology through Sigmund Freud's concept of the "death drive," or "Thanatos," a psychological force driving self-destructive behavior. This concept contrasts with "Eros," the life instinct named after the Greek god of love.

Thanatos has also inspired artistic interpretations throughout history. John William Waterhouse's 1874 painting Sleep and His Half-Brother Death portrays the two gods resting side-by-side, Hypnos bathed in light and Thanatos shrouded in shadow, reflecting their contrasting roles. Waterhouse's personal loss of his younger brothers to tuberculosis likely influenced his choice of this poignant subject.

Perhaps the most unexpected resurgence of Thanatos occurs in the Marvel Comics universe. Thanos, the powerful villain, takes his name and inspiration from the Greek god, seeking to court Mistress Death (Marvel's embodiment of death) by eradicating half of all life. This journey from ancient Greek mythology to modern comic books demonstrates the enduring power of this figure, his association with death resonating even in fantastical realms.

From ancient poetry to modern psychology and popular culture, Thanatos continues to capture imaginations. Though often overshadowed by other figures of the Greek pantheon, his presence endures, reminding us of the inevitable yet complex nature of mortality and the human fascination with it. He may be the silent hand of death, but his touch can be felt across millennia, a testament to the enduring power of Greek mythology.