Satan Triumphant: The Black Death in Germany

The Black Death’s onslaught across fourteenth-century Europe struck with particular ferocity in Germany, leaving social, religious, and political turmoil in its wake. Arriving around June 1348, the plague spread from three directions—eastward from France, northward from Italy, and outward from the Balkans—hitting Bavaria first, and then rolling onward to major commercial hubs such as Hamburg and the Hanseatic ports. Chroniclers wrote of entire towns in despair, religious orders falling into chaos, and widespread scapegoating that resulted in brutal persecution. Below, we trace the progress of the Black Death as it moved into the German-speaking lands, explore the rise of the Flagellant movement, and delve into the tragic wave of anti-Jewish violence that overshadowed an already catastrophic period.

The Plague Arrives in Germany

By the middle of 1348, the pestilence known as the Black Death had already devastated regions of France, Italy, and the Balkans. Germany, split into numerous principalities, city-states, and ecclesiastical territories, could not hold the plague at bay. The disease quickly gained momentum, reaching Bavaria and then pushing northward. By the year’s end, it had struck Hamburg, Bremen, and other influential Hanseatic ports. As had been the case across Europe, attempts at quarantine, prayers, and other preventive measures did little to halt the contagion.

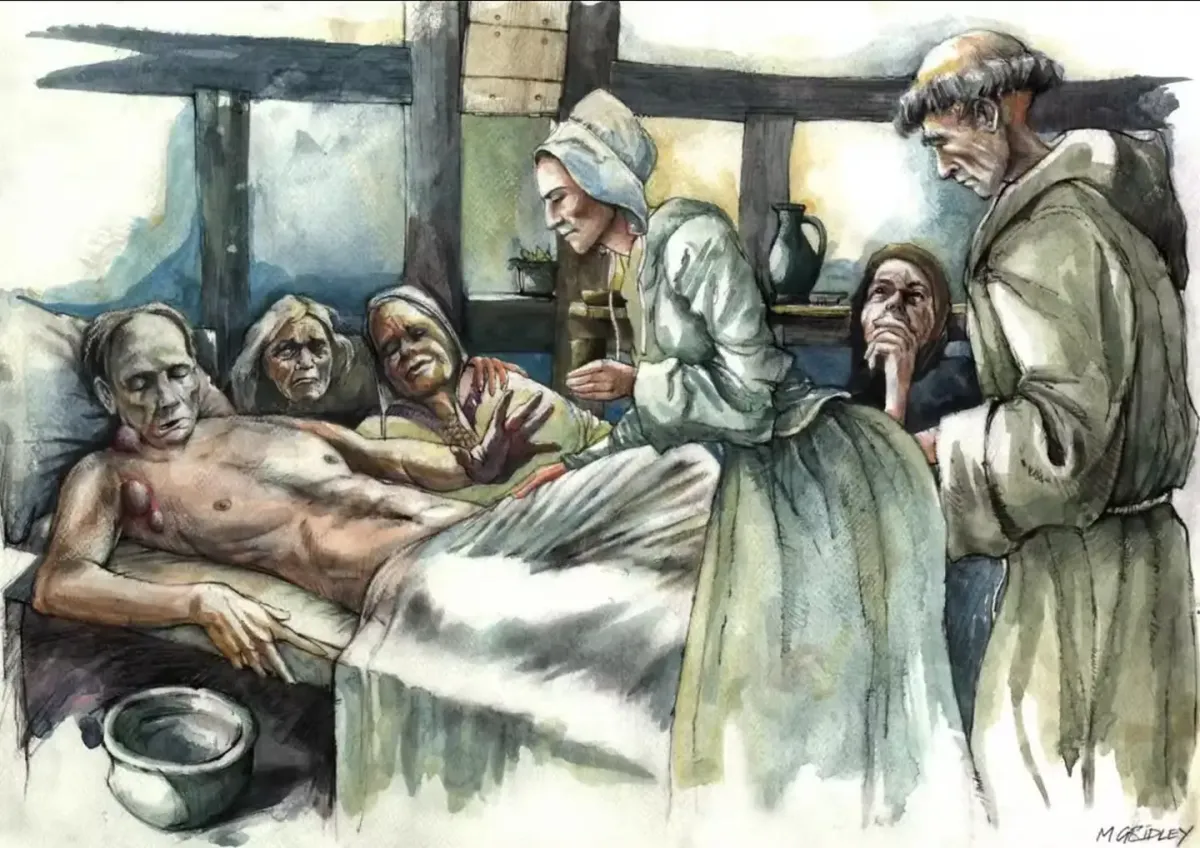

Mass Fatalities and Panic

Chroniclers recorded staggering death tolls in many of Germany’s urban centers:

- Frankfurt-am-Main: 2,000 deaths in 72 days

- Mainz: 6,000 dead

- Münster: 11,000

- Erfurt: 12,000

- Bremen: 7,000 dead across four parishes

- Vienna: Up to 500 daily deaths at one point, allegedly peaking at 960 in a single day

Given the limited medieval capacity for accurate record-keeping, some of these figures may be exaggerated. Still, they confirm that the epidemic’s impact was devastating and swift. In the city of Vienna, many inhabitants believed in a supernatural figure known as the “Pest Jungfrau,” or “Plague Maiden,” who reportedly drifted through the air in the form of a blue flame. Local folklore held that when she raised her hand at a victim, that victim would expire on the spot, exhaling a matching blue flame as proof of the Pest Jungfrau’s presence.

Despair and Symbolic Explanations

Such mystical personifications highlight how medieval societies struggled to comprehend mass mortality on this scale. Chroniclers in the Neuburg Chronicle noted that survivors were so overwhelmed by sorrow they wandered the streets in despair. Even wild animals—like wolves—were said to flee human settlements, as if frightened by the scale of death.

Legends of a female specter spreading plague were not confined to German-speaking lands. In Lithuania, stories circulated of a woman waving a red scarf at doors and windows, delivering sudden death. A hero in one village allegedly sacrificed himself by confronting this ghostly presence, severing her hand with a sword. Though he died, the rest of the village was said to be spared, and the severed scarf became a relic in a local church.

A Clergy Under Siege

While priests and monks across Europe suffered high mortality rates from the plague, Germany was notable for the sheer numbers of senior clergy who also died. Records suggest that at least 35% of the higher clergy perished—an unusual statistic, since one might expect wealthier clerics or bishops to live more secluded lives, shielded from direct interaction with infected commoners. Yet in Germany, even prominent church leaders were not spared.

Possible Reasons for Elevated Clerical Deaths

One explanation is that German clerics were, collectively, more active in performing their spiritual duties. In an era when the last rites were a fundamental act of charity, higher church officials in German lands may have chosen to tend to the dying in person rather than delegate tasks to lower-ranked priests. In doing so, they exposed themselves to infected households. Another possibility is that the plague was so widespread that none of the usual barriers—castle walls, high incomes, or hierarchical privilege—could halt the bacillus.

Moral Laxity and Monastic Decay

Mirroring trends elsewhere, some monasteries in Germany succumbed to a spirit of fatalistic revelry. In Ulm, monastic wealth reportedly vanished as monks, anticipating imminent death, decided to enjoy life while they could. Records suggest that riotous behavior, once unthinkable in a devout environment, became commonplace, eroding the moral and institutional foundations of the German Church.

By 1350, the German ecclesiastical structure faced a staffing crisis. Many priests had died, and those that remained often had to serve multiple parishes. For example, in one district, 13 priests held 39 benefices in 1347. After the plague, 12 priests were forced to handle 57. In desperation, church authorities lowered their standards for new clergy. Younger, poorly trained men donned priestly vestments in droves. Paradoxically, many churches had grown richer through legacies and donations left by the dying, even as they struggled to find qualified men to fill vacant positions. This mounting dissatisfaction would sow seeds of future reform movements, eventually culminating in Martin Luther’s Reformation nearly two centuries later.

The Rise of the Flagellants

Amid the chaos of the Black Death, popular religious movements emerged, none more dramatic or controversial than the Brotherhood of the Flagellants (often called the Brethren of the Cross). At their height in 1348 and 1349, they marched through towns and cities, performing public rituals of self-scourging. These acts, known as flagellation, were seen as a desperate form of penance intended to placate divine anger that had seemingly unleashed plague upon humanity.

Ancient Roots, Medieval Revival

The practice of religious self-flagellation was not new. It had deep roots in certain ancient Christian communities and appeared sporadically in medieval monasteries, especially in eleventh-century Italy. By the thirteenth century, rebellious “hermit” flagellants—like those led by Raniero of Perugia—claimed to have discovered evidence of God’s anger in angelic letters instructing them to atone for society’s sins.

Angel of Justification

In 1343, a letter supposedly delivered by an angel to Saint Peter’s Church in Jerusalem announced that the Black Death was a punishment from God. The letter further declared that only the newly revived Brotherhood of the Flagellants could restore God’s favor by publicly punishing themselves for humanity’s collective wrongdoings.

Spectacle on the Streets

Flagellant groups typically traveled in austere, organized processions, sometimes up to a thousand strong. Upon entering a town, they would file silently into the local church, then move to the public square. There, they enacted a ritual of confession, singing of hymns, and self-inflicted whipping:

- Forming a Circle: Stripped to the waist, the participants would circle around, chanting.

- Prostration: At a signal from their leader or “Master,” they dropped to the ground in poses that mimicked Christ’s crucifixion or symbolized specific sins.

- Scourging: Each flagellant wielded a scourge of leather straps tipped with metal studs. They whipped their backs until blood flowed, while three designated “cheerleaders” sang hymns or spiritual verses.

- Rising and Repetition: After several minutes, the group would stand, then drop again, continuing the cycle multiple times.

Spectators, often gripped with fear of divine wrath, sometimes believed that hosting such ceremonies might protect their towns from the plague. Attendance was huge; people prayed and wept in unison with the flagellants, and the local clergy often remained on the sidelines, stripped of their usual authority.

Rigid Rules and Hidden Realities

A standard pilgrimage with the Brotherhood lasted 33 days (matching the number of years in Christ’s life), with flogging rituals repeated three times daily. Members agreed not to bathe, change clothes, sleep in a bed, or speak with the opposite sex during this period. They also had to pay daily fees to cover communal food expenses—limiting participation mostly to those of some means. In principle, these rules ensured seriousness of purpose, but in practice, it is doubtful that every ritual was equally severe. Chroniclers mention horrifying scenes of individuals driving metal studs so deep into their flesh that they had to yank the scourge to dislodge it.

By their second year, the Flagellants were widespread, traveling through Hungary, Germany, Poland, and the Low Countries. Initially, even Pope Clement VI saw them as pious, albeit extreme. But soon, their numbers swelled, and extremism escalated. Some claimed the movement should last 33 years until humanity attained redemption. Tales circulated of miracles and holy visions, with blood-soaked rags elevated to relic status.

Turning Against the Church—and Each Other

As the Flagellants gained popularity, they grew bolder in challenging local clergy. They began to claim the power to absolve sins, undermining priestly authority. Some defrocked priests joined them, fueling an open confrontation with the official Church. Flagellants would at times forcibly interrupt Mass, chase priests from pulpits, and seize church spaces for their own rites. Their demands often included denouncing wealth and calling for radical changes in society—whether in the Church’s material splendor or in broader feudal structures.

Criminal Infiltration and Disease Spread

With fanfare and adulation came opportunists. Criminals realized that, by joining a Flagellant band, they could travel inconspicuously from town to town. Moreover, the plague itself infiltrated the ranks, leading Flagellants to inadvertently carry the infection wherever they marched. This combination of radical preaching, social disruption, and epidemic contagion alarmed secular and ecclesiastical authorities. Even ordinary citizens, initially enthusiastic, began to have second thoughts.

Papal and Secular Suppression

By late 1349, Pope Clement VI changed course. In a Papal Bull issued on October 20, he officially condemned the Flagellants, threatening them with excommunication if they continued. Regional rulers soon followed suit. The Bishop of Breslaw ordered a leading Flagellant burned at the stake. Manfred of Sicily pronounced that any group of Flagellants arriving on his shores would be executed. In Avignon, a band of Flagellants who defied the papal edict found themselves likewise threatened. Although smaller enclaves of the Brotherhood lingered into the early fifteenth century, the movement’s golden era was over.

The Persecution of the Jews

Perhaps the darkest facet of the plague years in Germany—and indeed, throughout much of Europe—was the violent scapegoating of Jews. Rumors proliferated that Jews were responsible for poisoning wells, producing the “miasma” that infected Christians with the Black Death. Frenzied mobs, sometimes incited by newly radicalized Flagellants, turned rumor into pogrom, unleashing some of the most brutal mass killings in medieval European history.

Groundless Accusations

The claim that Jews caused the plague by contaminating water sources found fertile ground in a climate of fear and ignorance. Elaborate conspiracies were spun:

- A secret network based in Toledo supposedly coordinated the poisoning.

- “Imported Oriental powder” was used to pollute wells.

- Jews also forged currency and sacrificed Christian children in hidden rituals, so the rumors said.

These heinous falsehoods spread, and violence erupted swiftly. Cities that had not even been struck by plague sometimes turned on their Jewish populations purely out of terror that the plague might come.

Early Massacres

In the spring of 1348, French cities like Narbonne and Carcassonne exterminated entire Jewish communities. By autumn, the infamous trial at Chillon produced confessions—extracted under torture—of Jewish involvement in well-poisoning. These alleged admissions included references to a Rabbi Peyret and a supposed ringleader, Rabbi Jacob of Toledo. Though Pope Clement VI argued that Jews were dying from plague just as Christians were, his appeals largely fell on deaf ears.

Murders Escalate in Germany

Germany saw some of the worst anti-Jewish violence:

- Frankfurt: When Flagellants arrived in the summer of 1349, they descended on the Jewish quarter in a massacre.

- Brussels: The mere approach of a Flagellant band incited locals to kill 600 Jews.

- Basle: Jews were locked in wooden houses and burned alive.

- Mainz: After some Jews fought back, killing 200 Christians, reprisals led to the deaths of an estimated 12,000 Jews.

- Strasbourg: Even before the plague reached the city, anti-Jewish fervor boiled over; over 2,000 Jews died on Valentine’s Day in 1349.

These atrocities were often accompanied by theft: attackers searched victims’ garments for hidden gold. In some cities, the Jewish population preemptively destroyed their valuables or set fires rather than let their persecutors profit. At Esslingen, Jews barricaded themselves in their synagogue and committed mass suicide by burning the building to the ground.

Resistance to Violence

Papal edicts condemning pogroms and threats of excommunication mostly failed to quell the mobs, whose hatred was bolstered by centuries of Church-fueled suspicion. However, a few secular rulers intervened to protect Jews:

- Ruprecht von der Pfalz (the Palatinate): Offered personal protection to Jews on his lands, earning him the derogatory nickname “Jew Master” and sparking fierce local opposition.

- Casimir III of Poland: Largely prevented mass violence against Jews within his kingdom. Political rivals claimed he did so only because he was in thrall to his Jewish mistress, Esther; nonetheless, the fact remains that Polish Jews were significantly safer than those in much of Western Europe.

Unfortunately, such figures were the exception. By 1350, entire Jewish communities had vanished from some parts of Germany. Survivors fled eastward, seeking refuge in territories with stronger laws or more tolerant rulers. This mass migration would reshape the distribution of Jewish populations, paving the way for new centers of Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

Aftermath and Echoes of Reform

By the turn of 1350, the worst wave of the plague was receding, leaving behind a Germany irrevocably changed. Hundreds of thousands had died. Surviving towns found themselves short-staffed, riddled with economic and social dislocation, and haunted by the memory of violent strife. The Church, ironically enriched by bequests but weakened by clerical casualties, would struggle to restore its moral authority. Populations that once placed unquestioning trust in the clergy now viewed it with skepticism. The Flagellant movement, once embraced as a tool of divine mercy, revealed the dangerous potential of uncontrolled religious fervor.

Seeds of Future Change

Many historians see a line connecting the church’s compromised position in the mid-fourteenth century to later calls for reformation. In Germany, that culminated in Martin Luther’s theses in 1517. On the one hand, the Black Death and its fallout deepened religiosity for some, as fear of divine retribution remained strong. On the other, the visible corruption and chaos—culminating in monastic debauchery and incompetent clergy—sowed popular disillusionment that would burst forth in subsequent centuries.

Shattered Communities

Meanwhile, the dissolution and forced exile of Jewish communities left a cultural vacuum in many city-states. The violence that accompanied the Black Death underscored how communal panic and misguided conspiracies can lead to ruinous persecution. The resultant diaspora and spread of Jewish enclaves to Eastern Europe would shape the cultural tapestry of the continent well into the modern era.

A Grim Legacy

Medieval chroniclers sometimes referred to the plague as “Satan triumphant,” capturing the widespread sense of apocalyptic doom. In Germany, that phrase resonates painfully. The plague struck with extraordinary force, but it was human cruelty and scapegoating that reached its own horrifying zenith. Cities that might have emerged from the Black Death determined to rebuild instead became sites of monstrous atrocity, overshadowing all illusions of devout Christian unity.

Conclusion

The German experience of the Black Death was both a microcosm of the broader European crisis and a singularly intense tableau of horror, piety, and upheaval. The raw devastation of towns like Erfurt, Münster, and Bremen mirrored the plague’s grim toll across the continent. Yet Germany’s higher clergy mortality rate, the fervent explosion of Flagellant processions, and the savage pogroms against Jews marked the epidemic’s course with unique features.

In the midst of seemingly endless funerals and empty streets, some found meaning through extreme penitential rituals; others latched onto bigoted rumors that fueled mass violence. The urgent shortage of priests shaped church governance for generations. Anti-Jewish riots—and occasional heroic defenses—redefined social contracts and propelled a significant portion of Jewish life deeper into Eastern Europe.

Centuries later, many of the issues that emerged from this crisis—lack of institutional accountability, scapegoating of marginalized communities, and the complex interplay between faith and suffering—still cast their shadows on historical memory. Understanding Germany’s experience with the Black Death thus underscores how medieval society, caught in a spiral of desperation, could produce both profound acts of devotion and unspeakable brutality. The plague’s passage was more than an epidemiological disaster: it was a crucible that tested every aspect of social, religious, and moral life, leaving behind fractured landscapes haunted by the echo of its mortal toll.