How Myth and Female Power Shaped Roman Society

Even though ordinary Roman women were denied formal political rights, the influence of powerful women in Rome is undeniable.

Through ancient history, few stories are as paradoxical as Rome’s transformation of Greek culture. Rome not only appropriated Greek gods and art but also absorbed Athenian attitudes toward masculinity and the roles of women—even as both societies nurtured misogynistic origin myths. Yet amid the contradictions, Roman women managed to carve out unique spaces of influence within a rigid patriarchal system.

Roman Adoption of Greek Culture

The Roman conquest and assimilation of Greek culture is one of history’s most remarkable cultural fusions. Rome stole the gods of the Greek pantheon and simply renamed them—Zeus became Jupiter, Aphrodite turned into Venus, and so on. This process of reinterpretation extended to the art and sculpture that the Greeks had perfected over centuries. Roman artisans copied Greek statues and paintings, incorporating their techniques into what became a distinctive yet derivative Roman style. Along with these visual and religious elements, the Romans also adopted Athenian attitudes towards masculinity and women, reflecting both admiration and deep-seated skepticism toward the roles assigned to each sex.

Yet, while the Romans may have copied much from the Greeks, they also possessed their own mythic traditions that revealed a more complex view of gender and power. One origin myth tells of Rome’s founding by the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, with their mother Ilia playing a critical—if underappreciated—role in the saga. In another myth, reminiscent of the Greek psychomachia, Rome’s birth is linked to a violent episode in which male marauders from Alba attack neighboring Sabines and kidnap their women. This dark narrative, in which marriage is sanctified under the notion of “confarreatio” (derived from the Latin word for grain, suggesting the sharing of sustenance), lays the foundation for a society where both heroic valor and brutal conquest are interwoven with a legacy of sexual violence.

Myth, Misogyny, and the Role of Women in Rome’s Early Narratives

Rome’s mythic origins are steeped in violence and patriarchal power. The story of the Sabine women, for example, underscores a recurring theme in Roman lore: the use of rape and abduction as mechanisms to secure alliances and consolidate power. This myth not only rationalizes the subjugation of women but also reinforces the idea that female bodies and sexuality were commodities to be controlled in service of the state.

In stark contrast to this violent myth, archaeological discoveries in places like Paestum—located south of Naples—reveal that the Italian peninsula was home to a variety of cultural practices before Rome’s rise. Artifacts associated with goddess worship, including terra-cotta figurines and wine cups, dating back to the sixth century BCE, point to a tradition in which women and the divine feminine may have once held greater prominence. Further north, the Etruscans, who settled Tuscany around the eighth century BCE, were known for their advanced art, writing (which has yet to be fully deciphered), and prophetic practices. Notably, the Etruscans traced descent through the maternal line and celebrated a social life in which husbands and wives shared responsibilities—a stark contrast to the later Roman model.

The Roman myth, with its focus on abduction and the conquest of women, marked a clear departure from these earlier traditions. By emphasizing a narrative of rape and subjugation, Roman society laid the groundwork for a system that would legally and culturally enshrine male dominance. Yet, even within this oppressive framework, certain institutions hinted at a more nuanced reality. The founding of the Vestal Virgins, for example, is attributed in some legends to Rhea Silvia (also known as Ilia). These priestesses were charged with guarding the sacred hearth of Rome and symbolized a vestige of an earlier, more woman-centered society—one that aimed to convert the private devotion of family loyalty into a broader state ideology.

The Roman Republic and the Centrality of Family

Roman history is traditionally divided into two periods: the Republic (roughly 300 BCE to 30 BCE) and the Empire (from 30 BCE until about 500 CE). During the Republic, power was held by wealthy landowners who ruled through a Senate. This aristocratic system was fiercely family-centered. Land was the primary source of wealth and passed down through generations, ensuring that familial lineage and reputation were of paramount importance.

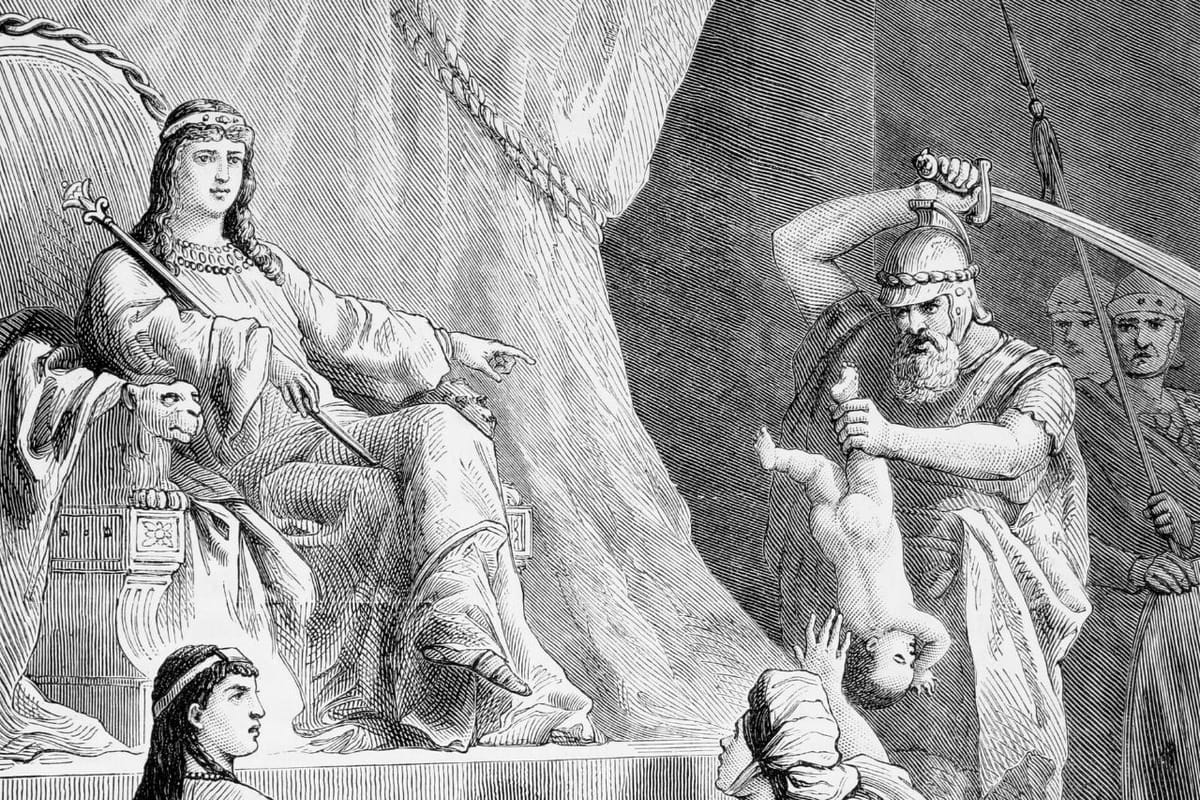

In the Republic, the concept of paterfamilias—or absolute fatherhood—was a cornerstone of Roman society. The patriarch of each household held “patriapotestas,” the complete legal authority over his children and other dependents. This power extended even to the point where a father could decide whether a newborn should live or be exposed to death. Roman women, like their male counterparts, were defined in legal terms by their relationships within the family. A woman’s identity was not her own; it was marked by the name of her father or husband. For instance, a daughter would be identified simply as belonging to the family of a prominent male figure, such as “Julia” to denote her connection to the Julii.

Despite these restrictions, Roman society was also marked by a strong sense of family duty and loyalty. Early Roman history celebrated the heroic deeds of aristocratic women who were seen as saviors of the state. These women were often credited with actions that ensured the safety and continuity of their families and, by extension, Rome itself. The institution of the Vestal Virgins is one such example. These women, chosen from prominent families, were tasked with maintaining the sacred fire of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth—a duty that symbolized both their personal chastity and their indispensable role in the well-being of the state.

Roman Women: Between Subjugation and Autonomy

Although Roman law was inherently patriarchal—defining women as “defective” or “imbecile” in legal terms—the lived reality of women in Rome was more complex. While women were legally placed under the perpetual guardianship of their fathers or husbands, they also managed to gain a measure of independence within the family unit. Wealthy Roman women, especially those from prominent families, sometimes found ways to assert influence. They could choose the form of marriage they desired, opting to remain under the nominal control of their fathers rather than fully transferring their legal identity to their husbands. By spending three consecutive nights each year in their father’s house, a woman could avoid being completely subsumed into her husband’s authority, thereby retaining some control over her dowry and personal property.

As time passed, changes in marriage laws and inheritance practices allowed women to secure rights that were not available in earlier periods. By 300 BCE, noble girls were receiving an education, and by 200 BCE, even plebeian girls attended school in public spaces until they reached their early teens. By the turn of the era, many marriage contracts were based on mutual consent rather than mere familial arrangements. Although Roman women could never practice a profession in the same way as men, some wealthy matrons managed to study subjects like law, politics, or literature, even if they were not allowed to earn a living from these pursuits.

Roman society also celebrated a culture of athleticism and public life for women in certain contexts. In the ruins of a Roman villa at Piazza Armerina in Sicily—dating back to the fourth century BCE—mosaic floors depict scenes that suggest both leisure and physical prowess. In what some guides refer to as the “bikini girls” room, women are shown engaging in athletic competitions: throwing the discus, hurdling, playing ball, and lifting weights. Such imagery stands in stark contrast to the grim legal reality for most women, yet it underscores a dual aspect of Roman life where elite women could, under specific conditions, exercise a surprising degree of freedom and even command public respect.

Warfare, Social Unrest, and the Shaping of Roman Society

Throughout its history, Rome was a state almost perpetually at war. Its military conquests spread Roman law and culture across vast territories—from Greece and Asia Minor to Egypt, Gaul, and even the far reaches of Britain. However, constant warfare also had profound effects on domestic society. In the early Republic, only landowners could serve as soldiers, and they would often leave their farms to join the military, entrusting their lands to slaves. Upon returning, many of these small farmers found their properties absorbed into larger estates owned by the wealthy. The growing gap between rich and poor fueled social unrest, and the plight of the slave population became a recurrent issue, leading to several revolts.

One of the most famous of these uprisings was led by Spartacus in 73 BCE, when a slave rebellion nearly brought Rome to its knees. Though ultimately suppressed, such revolts exposed the inherent contradictions in a society that celebrated military prowess yet relied on the brutal exploitation of the underclass. The same contradictions extended to the roles of women. While elite women in the Republic could maneuver within the constraints of family law and sometimes even influence public affairs behind the scenes, the vast majority of poor and slave women labored under harsh conditions. They worked as weavers, fullers, butchers, and merchants on the crowded streets of Rome, striving to survive in an urban landscape defined by inequality and relentless competition.

The Transition to Empire and the Transformation of Family Laws

With the end of the Republic and the rise of the Empire under figures like Julius Caesar and his heir Octavius (later known as Augustus), Rome underwent significant transformations. Octavius, seeking both legitimacy and a return to what he regarded as the moral “good old days,” initiated a series of reforms that would reshape family life and gender roles. In 18 BCE, the lex Julia de Adulteriis and, later, the lex Papia Poppaea in 9 CE were enacted to strengthen the institution of marriage and promote childbearing. These laws made marriage compulsory and imposed penalties for adultery, effectively attempting to control the sexual behavior of Roman citizens.

Under these new legal frameworks, the family became an even more rigid institution. Marriages were not only personal unions but also political and economic contracts designed to ensure the continuity of property and social order. Men were compelled to marry by a certain age, and girls were expected to wed shortly after reaching puberty. Although these laws sought to curb the behaviors that might undermine the stability of the state, they also further entrenched the idea that women were secondary to men in every aspect of life.

Yet, even as the state imposed strict controls, some Roman women found ways to exert influence within the confines of the law. Elite women, though still legally subordinated, often managed vast estates and participated indirectly in political life through their familial connections. The social reforms of the early Empire thus created a paradox: while public law reinforced male authority, in practice, many women—especially those from wealthy families—became adept at maneuvering through the legal and social labyrinth to secure their own power and wealth.

Female Influence in the Imperial Court

One of the most striking aspects of the Roman Empire was the role played by influential women behind the scenes of imperial power. Livia, the wife of Augustus, is a prime example. Granted unprecedented privileges—including the Right of Three Children—Livia managed her own estate and provided critical counsel to her husband. Although she was never allowed to formally enter the Senate, her influence was undeniable. In fact, after Augustus’s death, Livia was posthumously adopted into the imperial family, and her eventual deification hinted at the recognition of her power and contribution.

The trend of female influence continued with successive emperors. Empress Plotina, wife of Trajan, the imperial matriarch Cornelia, and other women in the imperial family played significant roles in state affairs. Their influence was personal and contingent on their relationships with the reigning emperors, rather than being institutionalized in any lasting manner. Even as laws increasingly restricted women’s public roles, these individual figures managed to shape policy, guide imperial decisions, and, in some cases, even participate in military matters.

By the third century, the trend of powerful female kin continued with the rise of Septimius Severus. His wife, Julia Domna, and her influential family—comprising sisters and daughters who wielded considerable power—demonstrated that even in a state defined by patriarchal norms, exceptional women could rise to prominence. Although these women’s authority was ultimately derived from their connections to male rulers, their impact on the empire was profound. Whether through direct intervention or subtle manipulation, these women helped maintain a period of relative stability and peace in an otherwise tumultuous era.

The Shifting Image of Roman Women

Over time, the public image of Roman women shifted from that of heroic figures in early myth to the ideal of a virtuous, obedient wife and mother. Biographies and literature began to idealize women who sacrificed their ambitions for the sake of family and state stability. Figures such as Portia, the wife of Brutus, and Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi brothers, were celebrated for their selflessness and moral fortitude. In contrast, assertive women who challenged these norms were often portrayed as viragos—enemies of the state whose ambition and sexual independence were condemned.

This idealization was part of a broader cultural project to stabilize Roman society by reinforcing strict gender roles. While women from elite families could, in certain cases, influence political and economic affairs behind closed doors, the dominant cultural narrative emphasized that a woman’s proper role was to support her husband and maintain the household. Public expressions of female assertiveness were discouraged, and in many ways, the legal and social restrictions placed on women during the Republic were further tightened under the Empire.

Despite these restrictions, however, the reality for many Roman women—especially common, poor, and slave women—was one of resilience and resourcefulness. While elite women might have navigated the corridors of power, the vast majority of women in Rome worked tirelessly to sustain their households and contribute to the economy. These women ground grain, wove textiles, and managed small businesses on the bustling streets of Rome. Their labor, often overlooked in historical narratives, was essential to the functioning of the empire.

The Enduring Legacy of Roman Female Power

Even though ordinary Roman women were denied formal political rights such as voting or holding public office until centuries later, the influence of powerful women in Rome is undeniable. Through familial alliances, estate management, and subtle political maneuvering, women like Livia, Plotina, and Julia Domna managed to shape the policies and direction of the Roman state. Their achievements, however, were largely personal rather than institutional—they did not lead to a broader inclusion of women in the governance structures of Rome. Instead, their power was confined to the realm of the private sphere, where the support of the family and the authority of the household could be leveraged to influence the state indirectly.

The complex interplay between legal restrictions and social realities created a unique dynamic in Roman society. While women were legally defined as subordinate and often reduced to mere designations tied to their male relatives, in practice many managed to navigate these constraints with surprising ingenuity. They were not given the right to vote, run for public office, or serve on juries until much later in history, yet their influence in family and economic life was significant. Even in times of political strife and war, women played critical roles—whether as the guardians of the household or as the quiet strategists behind powerful emperors.

The legacy of these powerful Roman women continues to be a subject of fascination and debate among historians. Their stories challenge the simplistic narrative of ancient patriarchy by revealing the nuances and contradictions inherent in Roman society. While the overarching structure was undoubtedly dominated by men, the instances of female empowerment that emerged—however sporadic and dependent on individual talent—offer a reminder that even within rigid systems, the seeds of change can be sown.

Keep reading: