How Greek Seers Shaped Warfare and Took Risks on the Battlefield

Ancient Greek warfare was saturated with ritual, as generals believed success required more than physical readiness: it needed divine assent

When we imagine ancient Greek warfare, we tend to focus on hoplites, phalanxes, and strategic masterminds such as Leonidas or Alexander the Great. Yet behind many of these military operations stood a figure whose influence, though more subtle, was often decisive: the seer. Seers (manteis) accompanied generals on campaigns, performed sacrifices and read omens (hiera and sphagia) to determine when—or whether—to launch an attack. While some modern perspectives have tended to dismiss them as mere tools of propaganda, a fuller view reveals how integral seers were, how precarious their role could be, and why armies prized their counsel so highly.

Below, we’ll explore the seer’s function in Greek warfare: from public sacrificial rituals to behind-the-scenes negotiations and occasional acts of genuine initiative. We’ll see why the job was both influential and fraught with risk, how seers balanced subjective interpretation with an aura of objectivity, and how the high-stakes military environment impacted their fortunes—or led to their downfall.

Learn the art of seer in ancient Greece

The Seer’s Critical Role on the Battlefield

For a long time, scholars tended to treat seers as mere mouthpieces for generals seeking to justify predetermined plans. In this rationalizing view, if a general wanted to attack, the seer conveniently “found” good omens. If the general preferred delay, the seer cited unfavorable signs. More recent research, however, paints a more nuanced picture:

- Seers and generals often formed a symbiotic relationship, each needing the other’s expertise and authority.

- Even if subconscious biases influenced the seer’s reading of entrails or animal movements, long-term credibility required some measure of genuine independence.

- When the stakes were high, “favorable omens” that misaligned with reality could ruin a seer’s reputation, even more than a general’s.

The interpretative core of divination was inherently flexible—no two sacrificial livers look exactly alike, and determining what shape or color signified a “bad omen” often left room for judgment. Nonetheless, certain unmistakable signs (like a liver lacking a lobe) were conventionally understood to be unequivocally bad. Thus, seers balanced strategic awareness with maintaining a reputation for genuine insight.

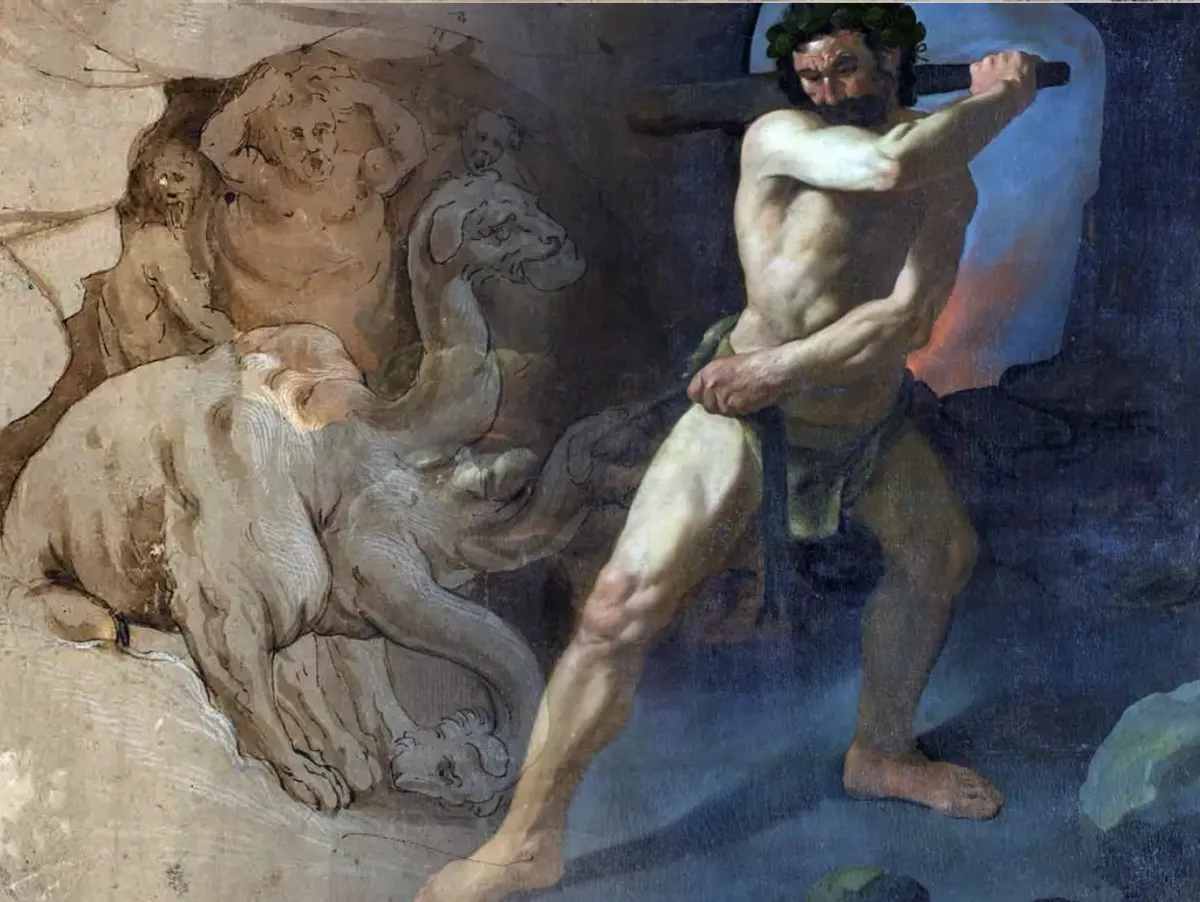

King Leonidas of Sparta consulted the oracle before the battle with the Persian (Movie 300)

The Seer’s Power and Pressure

Crucially, ancient Greeks believed that the gods themselves had strategic sense and would communicate their will through sacrifices. The seer’s reading could prevent an army from moving forward or encourage a bold strike. Ignoring a seer’s warnings, as the Greeks saw it, invited divine wrath. In literature and lore, generals who scorned their seers often faced disaster.

At the same time, the seer’s role was a public performance. Standing before an entire army, sacrificing an animal and interpreting its entrails with arrows already flying overhead demanded calm under pressure. A single unfavorable omen could halt an eager force; a single favorable sign could propel them to charge headlong. This high-stakes context shaped the interactions between generals and seers and often placed the seer under extraordinary stress.

Sacrificial Rituals: Hiera and Sphagia

Hiera: Campground Sacrifice

When Greek armies gathered in camp, preparing to march or engage, the seers performed hiera. These sacrifices typically involved examining the entrails—especially the liver—of a sheep (or another animal) to see if the gods “approved” a certain course of action. This reading would guide the day’s activities. If the signs proved unfavorable, generals often delayed movement, sometimes multiple days in a row, seeking a reversal through repeated sacrifices.

Sphagia: Battle-Line Sacrifice

By contrast, sphagia was the final sacrifice right before battle. The seer slit the throat of a young she-goat or similar sacrificial victim, observing how the blood flowed and how the animal fell. A positive sphagia signaled that the gods permitted the army to advance. A negative one could stall even the most determined force. In many depictions—on vases and in reliefs—we see a figure in a helmet, sword in hand, cutting the victim’s throat while the general watches, arm raised in prayer.

Unlike hiera, sphagia was more immediate and symbolic. It not only served as a divinatory check but also as propitiation—the animal’s death simultaneously “stood in” for the coming deaths of the enemy and protected one’s own soldiers.

Seers Influencing—or Even Setting—Strategy

Although often the seer functioned as a consultant, some sources show seers spearheading campaigns. Herodotus records examples of seers prompting direct action:

- Cleander of Phigalea convinced the slaves at Tiryns to rise against their Argive masters, initiating conflict (Hdt. 6.83).

- Tellias, an Elean seer, reputedly devised a clever ruse to drive off invading Thessalians (Hdt. 8.27).

Thucydides adds to this picture with Theaenetus, who partly planned the escape of Plataean defenders (3.20.1). While these incidents may be exceptional, they underscore that seers sometimes stepped beyond ritual to become active strategists.

Seers could even be central to conspiracies. Xenophon notes that in the anti-Spartan conspiracy of Cinadon, one of the key participants was the seer Tisamenus (descended from the illustrious Tisamenus of Plataea fame) (Xen. Hell. 3.3.11). Another example is Theocritus in Thebes, who helped Pelopidas overthrow an oligarchy in 379 B.C. and then recommended the critical sacrifice before the liberation of the city (Plut. Mor. 575b–598f). Such ties highlight that seers held enough charisma and religious prestige to be vital allies—or dangers—to any regime.

When Generals and Seers Disagree

A striking theme in Greek military narratives is the army’s strict adherence to omens. Xenophon’s Anabasis recounts multiple episodes where negative entrails halted movements despite dire hunger or impatience.

- At Calpe, the Ten Thousand starved for three days, awaiting a change in sacrificial fortunes.

- Later, they wanted to ravage the Tibarenians’ land but repeatedly got poor omens until they made peaceful passage instead (Anab. 5.5.1–4).

Herodotus similarly describes how seers on both sides at Plataea delayed the final clash with the Persians until the gods signaled approval (9.37–45). Sometimes, generals bucked negative omens out of desperation, occasionally paying with their lives—like Anaxibius, who fell into an ambush after ignoring a seer’s advice (Xen. Hell. 4.8.35–39).

Even strong believers acknowledged the potential for fraud. A famous (though possibly apocryphal) anecdote recounted by Polyaenus describes a Babylonian seer named Soudinus who “palmed” the words “victory of the king” onto a sacrificial liver—astonishing and encouraging the troops who believed the gods themselves had inscribed the message. It’s telling, though, that this story is attributed (in various forms) to several different periods and generals. The rarity of concrete examples in classical sources suggests that outright trickery was the exception, not the norm.

Moreover, many recognized that convenient negative omens could be just as useful for a general who needed to save face. For instance, Agesilaus and Alexander both stopped advancing after receiving unfavorable signs when, in fact, other strategic or logistical problems made further progress untenable. In Greek thought, if the gods deny you permission to continue, you are spared humiliating human defeats.

Seer as a Partner

The historical record brims with examples of generals forming lasting bonds with particular seers:

- Pausanias (the Spartan regent) and Tisamenus of Elis at Plataea (479 B.C.)—young aristocrats forging a vital bond in the culminating battle against Xerxes’ invasion.

- Tolmides and Theaenetus in mid-fifth-century Athens (Paus. 1.27.5).

- Cimon and Astyphilus (Plut. Cim. 18).

- Nicias and Stilbides (Plut. Nic. 4.2, 23.5).

- Dion of Syracuse and Miltas (Plut. Dion 22–27).

- Timoleon and the seer Orthagoras.

Such partnerships were often intense. The general entrusted critical decisions to the seer’s readings; the seer’s reputation soared (and his earnings, too) when battles went well. Even if a battle or strategy failed, the seer could claim that the gods merely gave permission to fight, not a guarantee of victory.

The most famous example is Aristander of Telmessus, who served Alexander from the outset of his campaigns until around 328/7 B.C. Aristander interpreted dreams, eclipses, comets, and everyday sacrificial signs. At Gaugamela, sources show him riding alongside Alexander in a white mantle, pointing to an eagle flying overhead—a divine omen that roused the troops.

Alexander remained fervently reliant on seers (and other sacrificial experts) through all his campaigns, increasingly obsessed with omens in his later years. As his sense of his own quasi-divine status grew, ironically, he never abandoned the practice of checking the gods’ will, revealing that even a man who believed himself the son of Zeus still needed mantic counsel.

Why the Seer’s Job Was Perilous

Seers performed sphagia sacrifices mere moments before combat, typically in front of the first lines. Indeed, some sources mention light skirmishing had already begun. That put the seer in grave physical danger. Many were killed in battle:

- Megistias died at Thermopylae, though he foretold the deadly dawn (Hdt. 7.219).

- Hegesistratus of Elis, Mardonius’s seer at Plataea, later died at Spartan hands (Hdt. 9.37–39).

- An Athenian seer who fought with the democrats against the Thirty was the first man slain (Xen. Hell. 2.4.18).

Surviving casualty lists from Argos and Athens place seers’ names prominently, sometimes even above generals—suggesting high honor but also confirming they had been slain in the city’s service. Standing close to the front lines and publicly wielding a sword to slit an animal’s throat was hazardous work in a chaotic battlefield environment.

Despite the danger, the rewards could be enormous. Gifted seers who served the “right” employers might receive lavish landholdings or huge sums of gold. Herodotus claims Mardonius paid handsomely for Hegesistratus. Cyrus the Younger famously gave his seer Silanus three thousand gold darics for a single accurate prediction (Xen. Anab. 1.7.18). But not everyone reached those heights. Many others eked out a meager living; dream-interpreters and low-tier mantics appear to have wandered from city to city hoping to pick up fees, sometimes taxed by local governments (Arist. Oec. 1346b).

Were Seers Just Pawns?

One might ask: If generals hired and paid seers, weren’t seers entirely at their mercy? It’s clear some manipulations occurred—especially if one side needed to boost morale or if a general sought a graceful exit from a flawed plan. But for a seer’s long-term credibility, obvious deceit could destroy a career. Negative omens, especially if repeated, had to be respected or risk causing public cynicism about the seer’s skill.

Moreover, evidence like Xenophon’s Anabasis or Arrian’s account of Alexander shows cases where seers refused to revise unfavorable readings, even under direct pressure. They understood that their reputations—and possibly their lives—depended on being consistent with the “signs.” Over time, their position might gain credibility precisely because it was not an automatic rubber stamp.

Seers were seldom without employment options. If a campaign looked doomed, a savvy seer could exit with the explanation that “the gods withheld favorable omens,” shifting blame to the commander’s stubbornness. Some did exactly that. And if another potential employer saw the seer as reputable, he might secure better-paying work. Whether among local armies, tyrants’ courts, or traveling mercenary forces, seers formed a professional class with specialized knowledge, consistent demand, and substantial risks.

Conclusion

Ancient Greek warfare was saturated with ritual, as generals believed success required more than physical readiness: it needed divine assent. Seers stood at this intersection of human strategy and divine will. Their day-to-day tasks included:

- Conducting daily camp sacrifices (hiera) to gauge whether to march or stay put.

- Performing the dramatic battle-line sphagia moments before the armies clashed.

- Providing interpretations for prodigies, dreams, eclipses, and bizarre events that could sway morale and political decisions.

- Potentially advising on tactics or even orchestrating conspiracies or cunning ruses.

- Bearing personal risk as they accompanied troops into the thick of battle, sometimes perishing alongside the front lines.

Some seers became trusted partners and confidants of powerful generals, sealing their fortunes in campaigns across the Mediterranean and beyond. Others found themselves trapped between the expectations of their employer and the unpredictability of sacrificial omens. Still, the unshakable cultural belief that gods communicated through these rites gave seers a privileged—albeit dangerous—status.

Ultimately, the seer’s profession was both coveted and feared: coveted for its potential fame and fortune, feared because a single misreading or an ill-timed negative omen could end one’s livelihood, or one’s life. The capacity of seers to interpret divine signs, often as publicly as any political speech, embedded them deeply into the fabric of Greek warfare. While modern skepticism might view such rituals as manipulative showmanship, the Greeks themselves took the matter in earnest. Victory depended on men and gods together, and the seer was the crucial intermediary keeping that delicate alliance intact.