Gender in Ancient Greek Society

The same society that birthed democracy and celebrated intellectual achievement also institutionalized gender inequality and social stratification.

Ancient Greece is often celebrated for its achievements in philosophy, art, and politics. However, beneath the glittering achievements of democracy and cultural innovation lies a complex tapestry of power struggles, gender hierarchies, and social evolution.

The Indo-European Origins and the Mycenaean World

Around 1900 BCE, the first known inhabitants of the Greek peninsula and its islands were Indo-European peoples who settled the region and spoke an early form of Greek. These early settlers were predominantly farmers and herders, living in relatively egalitarian clans or tribes. Their society was organized around communal living with ad hoc leadership—individuals who led religious ceremonies and oversaw justice in informal, private settings.

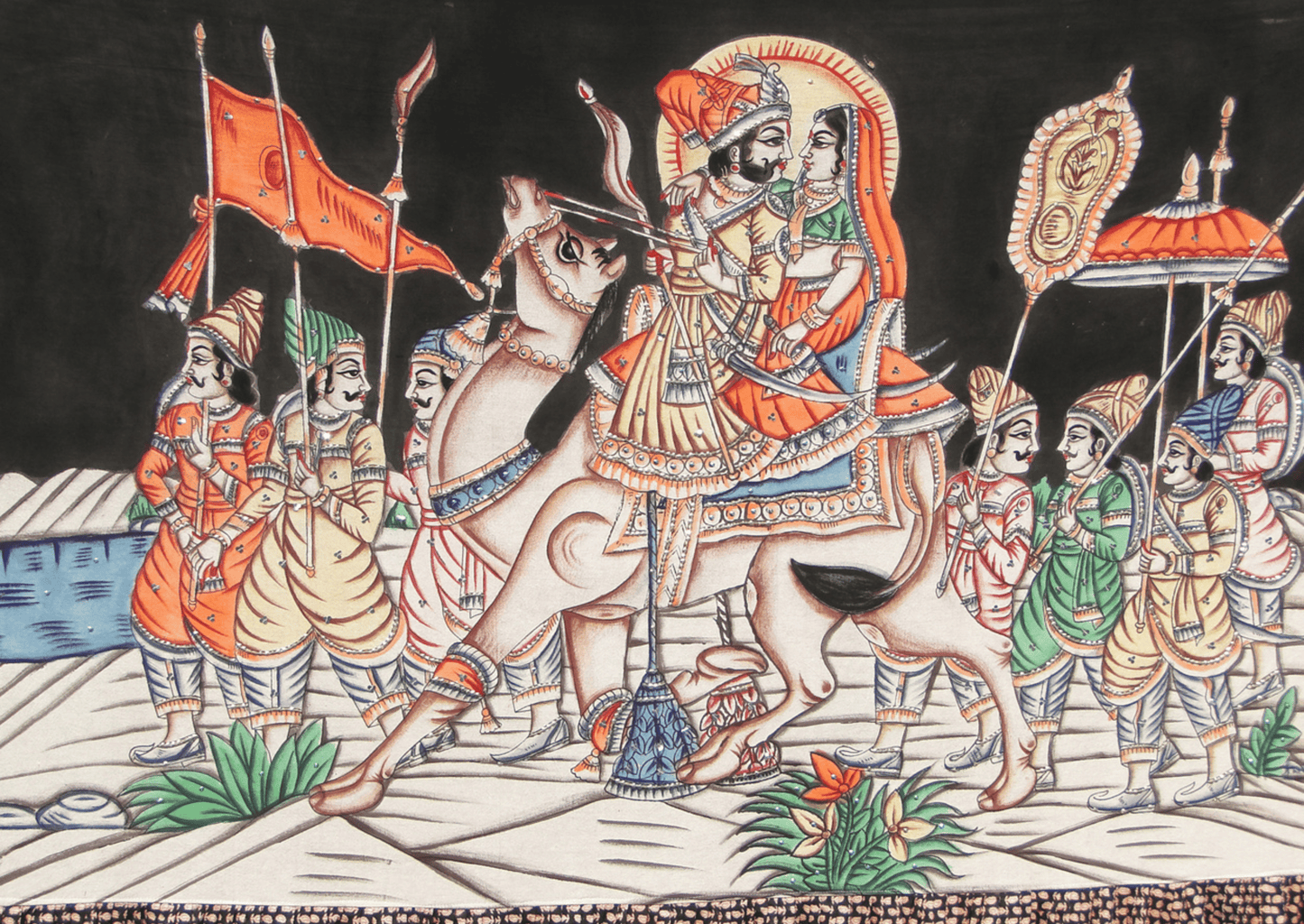

Mycenae soon emerged as a central hub in this early Greek civilization, its legacy immortalized in literature through the tales of Agamemnon, Klytemnestra, Elektra, and Orestes. Mycenaean society was characterized by a keen sense of record-keeping; the king and his bureaucrats meticulously cataloged material possessions—land, livestock, and even pottery. However, this prosperity was built on a slave society where the majority of slaves were women, underscoring an early pattern of gendered oppression.

The grandeur of the Mycenaeans is reflected in the impressive tombs they constructed for their rulers—a symbol of both wealth and the centralized power that defined their society. Yet, by 1130 BCE, the course of history shifted dramatically. Invading Greek Dorians, armed with iron weapons, overran Mycenae and left behind a legacy of destruction. Whatever treasures and achievements the Mycenaeans had built were burned to the ground, marking an end to one era and setting the stage for a new chapter in Greek history.

The Cult of Demeter and the Roots of Ancient Greek Religion

Religion in ancient Greece was as complex as it was influential. One of the earliest known religious practices was the cult of Demeter, centered at Eleusis. Demeter, revered as Mother Earth and the goddess of agriculture, was a pivotal figure in ancient Greek spirituality. Her narrative, intertwined with that of her daughter Persephone, revealed much about the society’s understanding of life, death, and seasonal change.

According to myth, Hades, the god of the underworld, abducted and assaulted Persephone, prompting a desperate search by Demeter. As the goddess roamed the Earth in anguish, the planet began to wither and grow barren—a mythic explanation for the onset of winter. In a bid to restore balance, Zeus intervened with a conditional promise: Persephone would be released provided she had not eaten anything in the underworld. However, Persephone had consumed a few pomegranate seeds, binding her to Hades for a portion of the year. Thus, the cycle of the seasons was born—a poignant reminder of the interplay between loss and renewal.

What is particularly noteworthy about the cult of Demeter is its inclusivity. The religious rites at Eleusis were open to Greeks of all sexes and classes, offering a rare communal space in a society otherwise stratified by gender and social status. Even as later reforms and power shifts attempted to replace Demeter with other deities, the enduring influence of her cult highlighted the deep connection between religion, nature, and social cohesion in ancient Greece.

Early Greek Political Structures and the Rise of Oligarchy

By around 800 BCE, Greek society began to evolve significantly with the emergence of the city-state, or polis. These urban centers, marked by marketplaces and fortified boundaries, mirrored the structure of ancient Sumerian city-states. Each polis was essentially a state in its own right, typically ruled by a king and a council. Over time, the dynamics of power shifted as conflicts and internal struggles often led councils to depose kings, thereby giving rise to forms of governance that emphasized group rule.

This shift towards oligarchy—the rule by a small group of unrelated men—had profound implications for the status of women. In these systems, the absence of familial bonds among the rulers amplified male solidarity and reinforced the marginalization of women. With power concentrated in the hands of a few men, societal norms dictated that women remain confined to the domestic sphere. Their roles were strictly limited to household tasks, and they were often portrayed as subservient or even contemptible in both legal and cultural contexts.

The political models that emerged in ancient Greece were not unique to that time. Even today, many modern governments operate under systems that, in various ways, reflect the power dynamics and oligarchic tendencies seen in ancient Greek society. The historical roots of such structures reveal the longstanding association between concentrated male power and the exclusion of women from meaningful public participation.

Spartan Society: Warrior Culture and Female Autonomy

The rise of Sparta in the ninth century BCE marked a radical departure from other Greek city-states. Founded by Dorian invaders who conquered the Peloponnesus, Sparta quickly became synonymous with military might and strict societal organization. Following a fierce rebellion by the Messenians, the Spartans responded by ruthlessly suppressing any potential dissent. Leaders were murdered or exiled, lands confiscated, and the subjugated population—the helots—were forced into a life of serfdom to serve the Spartan elite.

Spartan society was meticulously divided into three distinct classes: the Spartiates (full citizens), the perioeci (free non-citizens involved in trade and manufacturing), and the helots (enslaved agricultural laborers). Full citizenship was reserved for a mere twentieth of the population. Unlike many contemporary societies, Sparta’s approach to governance was highly militaristic. Citizens were not allowed to engage in agriculture or business; instead, they underwent rigorous military training from an early age. Boys were taken from their homes at the age of seven and subjected to brutal discipline and rigorous physical regimens designed to instill absolute obedience and eliminate individuality.

One of the most striking aspects of Spartan society was its approach to gender. While most Greek city-states relegated women to subservient roles, Spartan women enjoyed considerable freedom and influence. In a society obsessed with military prowess, Spartan men were too preoccupied with controlling the vast helot population to dominate women. As a result, Spartan women were well-fed, educated, and even trained in athletics. They participated in public festivals, competed in sporting events, and were encouraged to cultivate both physical strength and intellectual prowess.

The comparative freedom of Spartan women stands in sharp contrast to the experiences of women in other parts of Greece. In Sparta, women could own and manage property, and by the fourth century BCE, they held significant economic power. Their influence was so notable that even prominent philosophers like Aristotle attributed some of Sparta’s social decline to the empowerment of its women. Yet, despite these relative advantages, the overall Spartan system was designed to prioritize military strength over individual liberties, a trade-off that left little room for dissent or personal ambition outside the state’s rigid framework.

Athenian Democracy and the Marginalization of Women

While Sparta exemplified a society dominated by military discipline and selective female empowerment, Athens emerged as the cultural and intellectual heart of ancient Greece. Athenian democracy is often celebrated as a pioneering experiment in self-governance and civic participation. However, the democratic ideals of Athens were inherently exclusive, reserved for a tiny fraction of the population. Only about 6 percent of Athenian inhabitants—adult males of citizen birth—were granted the rights and privileges of citizenship.

Athenian society was deeply patriarchal. From the earliest myths to the realities of everyday life, women were systematically marginalized. The myths themselves often served as allegories for male dominance, depicting women as dangerous, emotional, and prone to excess. Literary and artistic representations reinforced the idea that women were subhuman—a view that justified their exclusion from political life and their relegation to the role of domestic laborers and sexual servants.

In Athens, the legal and social systems were meticulously designed to control women’s behavior. The term used for wife, “damar,” implied subjugation or taming. Bridal ceremonies were reminiscent of slave rituals, and strict laws governed every aspect of a woman’s public and private life—from the foods they could consume to the clothes they were allowed to wear. Women were confined to specific quarters in the home and were closely monitored by state-appointed guardians and police, ensuring that their movements and behaviors remained within the bounds dictated by male authority.

Furthermore, Athenian marriage was not founded on mutual affection or partnership but was viewed as a transaction meant to produce legitimate heirs. The institution was rife with coercion and often resembled a form of institutionalized rape. Marriages were arranged with little regard for the wishes or well-being of the women involved, who were expected to bear children and maintain the household while remaining in the shadows of public life.

The stark gender divide in Athens extended into every facet of life. While men engaged in public debates, athletic competitions, and symposia—leisure activities that were considered essential for cultivating citizenship—women were relegated to domestic drudgery. Even as elite Athenian men celebrated their intellectual and cultural achievements, they did so at the expense of a vast underclass of women and slaves whose labor and subjugation made such pursuits possible.

Cultural Reflections and the Impact on Western Ideals

The gender dynamics in ancient Greek society were not merely social arrangements; they were deeply embedded in the culture, literature, and even the religious practices of the time. Myths and legends reinforced the notion that male superiority was natural and divinely ordained. Stories of gods and heroes often involved the violent subjugation of female deities and mortals alike. Zeus’s infamous acts—from swallowing Metis to manipulating Semele’s fate—served as allegories for the relentless pursuit of male power at any cost.

These narratives played a crucial role in shaping Western cultural norms. The Greek portrayal of women as either dangerous seductresses or passive, subservient figures became a recurring motif in literature and art throughout the Western tradition. This legacy of female inferiority, deeply intertwined with biblical thought and subsequent legal frameworks, has had long-lasting repercussions. Even as modern societies have progressed towards gender equality, echoes of ancient Greek biases can still be found in cultural attitudes and institutional practices.

Yet, it is important to note that not all women in ancient Greece were without agency. In Athens, for instance, some exceptional women—like the poet Sappho and the intellectuals who defied societal norms—managed to carve out spaces for themselves despite overwhelming odds. In the rare instances when women were allowed to participate in intellectual pursuits, they left behind legacies that challenge the prevailing narrative of complete subjugation. Their voices, though often suppressed or recorded only by male contemporaries, offer a glimpse into the potential of a more inclusive society.

The Hellenistic Period: Change, Continuity, and the Reconfiguration of Power

The advent of the Hellenistic period brought about significant changes in the Greek world. Following the conquests of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great, Greek culture spread across vast territories, influencing regions from Asia Minor to Egypt and Persia. However, the legacy of earlier Greek society—particularly the rigid gender norms and hierarchical structures—remained deeply entrenched.

In some parts of the Hellenistic world, women began to experience modest improvements in their status. Although they were still legally dependent on a male guardian, women in certain states were granted the right to own property, participate in economic transactions, and even engage in public affairs to a limited extent. In contrast, Athens continued to enforce increasingly repressive measures against women. Laws were tightened, and social expectations remained rigid, with female inferiority still deeply ingrained in the cultural psyche.

The contrasting experiences of women in different parts of the Greek world during the Hellenistic period highlight the complexity of ancient Greek society. On one hand, economic prosperity and the spread of Greek culture allowed for incremental changes in gender relations. On the other, traditional norms and legal constraints continued to oppress the majority, ensuring that women remained largely voiceless in the public sphere.

Notable figures from this era, such as Hypatia of Alexandria, exemplify the potential for intellectual achievement despite these constraints. A mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher, Hypatia led the Neo-Platonist school in Alexandria and made significant contributions to science and education. Her life and tragic death underscore both the opportunities and the perils faced by women who dared to challenge the prevailing order.

The Legacy of Greek Gender Dynamics in Modern Thought

The structures and myths of ancient Greek society have had a lasting impact on Western civilization. The Greek definition of femininity—as subservient, dangerous, or inherently inferior—became intertwined with biblical and later cultural traditions, reinforcing patriarchal systems that have persisted through the ages. While modern movements have challenged these outdated notions, understanding their origins in ancient Greek thought provides valuable context for the ongoing struggle for gender equality.

Greek literature, art, and philosophy continue to influence contemporary debates about the role of gender in society. From the heroic epics that celebrate male virtue to the subtle portrayals of female suffering and resilience, the legacy of ancient Greece is a reminder of the complex interplay between power, culture, and human identity. The historical narrative of Greek society—its triumphs and its injustices—offers lessons that remain relevant today, as modern societies grapple with the legacies of inequality and seek to build more inclusive futures.

Reflecting on the Past: Lessons for Today

Ancient Greece remains a cornerstone of Western civilization, yet its history is a study in contrasts. The same society that birthed democracy and celebrated intellectual achievement also institutionalized gender inequality and social stratification. By examining the evolution of Greek society—from the egalitarian clans of early Indo-European settlers to the highly stratified and patriarchal systems of Mycenae, Sparta, and Athens—we gain insight into the complexities of human organization and the often painful trade-offs between progress and oppression.

The narratives of ancient Greece serve as both a celebration of cultural ingenuity and a cautionary tale about the consequences of unchecked power. The legacy of Greek mythology, with its dramatic tales of divine violence and human suffering, mirrors the realities of a society where the interests of a privileged few were enshrined in law and myth. In modern times, as we continue to fight for gender equality and social justice, the history of ancient Greece reminds us that cultural ideals—no matter how lofty—can be deeply compromised when they exclude and marginalize entire segments of the population.

In revisiting these ancient histories, we are compelled to ask: How do the power dynamics of the past inform our present? And what steps can we take to ensure that the lessons of history lead to a more equitable future? As scholars, activists, and citizens reflect on the ancient world, the stories of Mycenae, Sparta, Athens, and the Hellenistic realms continue to resonate, offering both inspiration and a stark warning about the costs of systemic inequality.

Keep readings: