Female Seers: Women’s Voices for Greek Divination

Ancient Greek culture is often associated with its pantheon of gods, heroic epics, and a deeply embedded patriarchal social order. Yet, within this landscape of myths and male-dominated spheres, women did hold prominent roles in specific religious contexts—one of the most striking being the craft of divination. While we often picture a male seer accompanying armies into battle or delivering prophecies to kings, the evidence for female seers—both mythical and historical—reveals a more nuanced reality.

The best-known figure is undoubtedly the Pythia, the priestess of Apollo at Delphi, but she was neither the first nor the only woman to practice the mantic arts. This post explores the vital and sometimes surprising place of female seers in Greek religious life, looking at myths, inscriptions, and testimonies from authors such as Herodotus, Plato, and Plutarch.

We will see how women’s voices contributed to the oracular tradition, how they were often viewed as conduits of divine power, and why their role raises challenging questions about agency, training, and authority in a society typically governed by men.

Learn the art of seers in Ancient Greece

Daughters of Teiresias and Divine Prophetesses

In Greek mythology, one cannot discuss seers without immediately thinking of Teiresias, the famed blind prophet of Thebes. Yet myths also speak of his daughters, Manto and Daphne, recognized as prophetesses in their own right. This detail highlights that from the very beginning of Greek imaginative literature, the notion of female seers was not alien. Indeed, Manto is remembered as the mother of Mopsus—himself a well-known seer—and Daphne, in some late traditions, was associated with Delphi. Myth places these women somewhere between mortals and semi-divine figures, unlike Themis or Phoebe, the original prophetesses at Delphi who were considered goddesses.

Despite the uncertain historical substratum beneath these figures, the legends reveal a persistent cultural acceptance of women in the realm of prophecy. The earliest prophetesses were divine, and then we see semi-mythical mortals like Manto and Daphne bridging the gap between the gods and everyday humanity. The various roles played by these female seers became part of the broader tapestry of Greek religion, paving the way for real-life women who would later serve as oracular figures.

Beyond Myth

When modern scholars think of a female Greek seer, the Pythia comes to mind almost automatically. However, the ancient sources (though often scanty) make clear that other women practiced divination too. They likely did not participate in the most visible sphere for seers—military expeditions—but that is not where mantic activities ended. Divination was also sought for healing, purification, private ventures, and rites of cleansing blood-guilt. Mythic precedents such as Melampus healing the daughters of Proteus, or Epimenides purifying Athens after the infamous Cylon affair, show how central seers could be to communal and personal well-being.

A crucial insight is that many such rites of healing and purification, performed away from the battlefield, might have been equally open to female specialists. Plato mentions ritual experts who could release individuals from blood-guilt by means of incantations and prayers, suggesting a pool of ritual activity not always documented by historians more interested in war and politics. In other words, behind the scenes, women could—and did—act as recognized seers, using “technical” methods of reading signs. They enjoyed a certain authority precisely because spiritual or medical rites were perceived as vital to personal and civic life.

Traces of Real Female Seers

Plato’s Symposium features Diotima, famously presented as a wise woman who educates Socrates about love and the nature of the divine. Although her historicity remains uncertain, Plato’s choice to depict an authoritative female figure teaching philosophical (and arguably mantic) truths indicates that his contemporaries found nothing inherently absurd in the notion of a female seer.

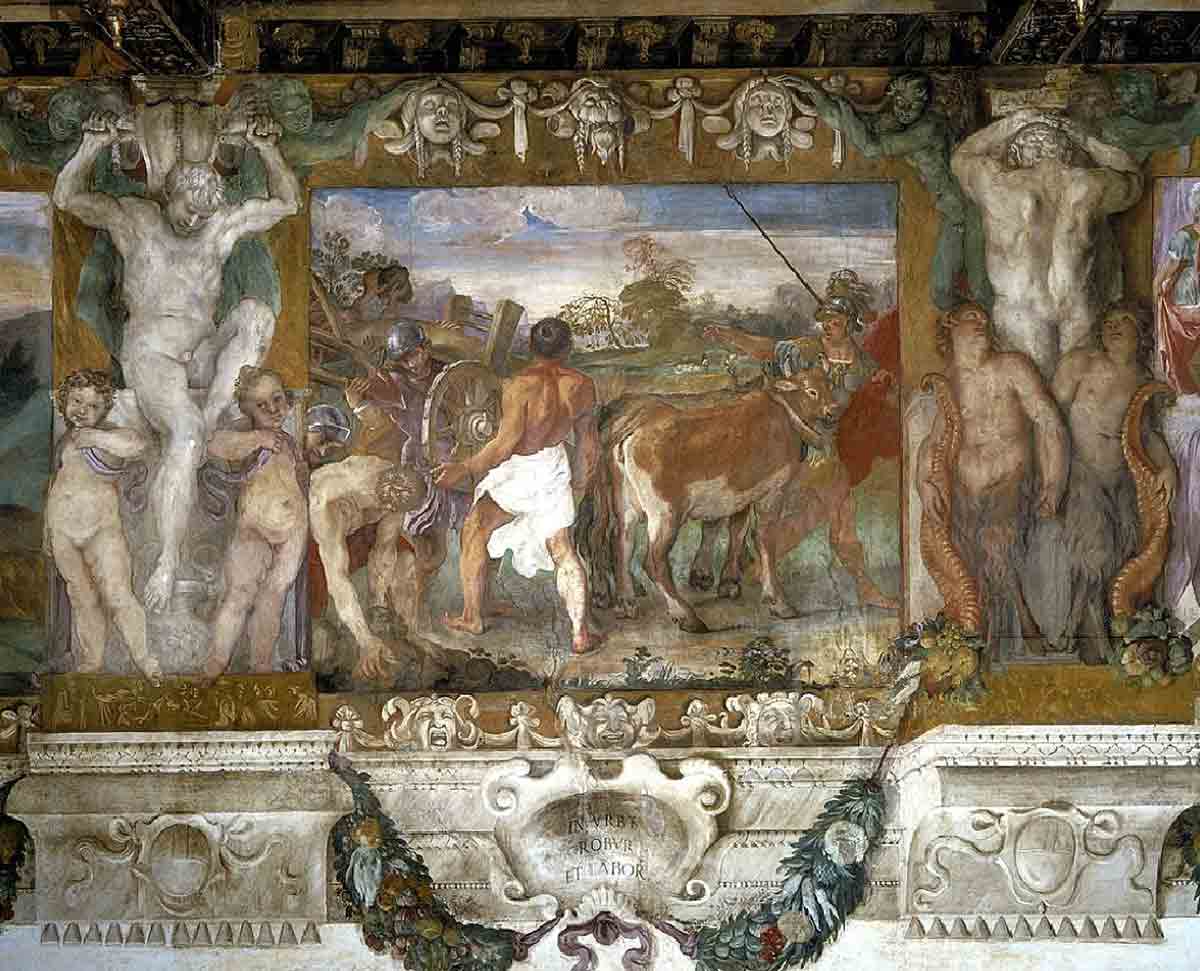

Even more compelling is an archaeological find from Mantinea: a late fifth-century grave stele showing a woman holding a liver in her left hand. Since hepatoscopy—the interpretation of liver omens—was a standard form of “technical” divination, it is difficult to interpret this iconography as anything other than a depiction of a female seer. Although singular in surviving ancient art, it confirms that real women indeed practiced extispicy, a technique often associated with male specialists on the battlefield. This woman from Mantinea, whether she termed herself “seer” or “priestess,” claimed the same authority and skill usually ascribed to male mantics.

Further proof of such female practitioners comes from inscriptions and literature in Hellenistic times. An epitaph from Larissa in Thessaly (third century BCE) bears witness to a woman named Satyra described simply as mantis—“seer.” Meanwhile, in a set of epigrams by the poet Poseidippus of Pella, we read of a female augur named Asterie who summons birds in order to divine the future. Both references show women recognized professionally by the title of seer, rather than merely as “assistants” to a male figure. They were distinct, legitimate experts in their own right, with the freedom to set up augural stations and interpret signs for their clientele.

The “Prophetic Garb”

Just as male seers had special attire—white tunics, laurel crowns, sacrificial knives—so did female seers. Cassandra in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon (lines 1264–70) alludes to wearing a prophetic robe and fillets around her neck, which signified her status as a prophetess of Apollo. The Pythia at Delphi was often depicted with a laurel branch and near the sacred tripod, items that symbolized the god’s presence and her unique mantic authority. Greek vase paintings, such as one showing the goddess Themis at Delphi, reinforce the close symbolic link between seating on a tripod and the power to speak for Apollo.

These visual and literary clues, while fragmentary, remind us that the presence of a woman in ritual contexts was neither anomalous nor hidden. On a practical level, the seer’s garments and tokens made her easily recognizable to potential clients. Moreover, they signaled to onlookers the seriousness and authenticity of her claims to divine inspiration.

The Pythia at Delphi

No discussion of female seers is complete without addressing the Delphic Oracle. When the term “female Greek seer” is used, most people picture the Pythia, perched on Apollo’s tripod in a chamber filled with vapors, delivering cryptic maxims to visiting pilgrims and statesmen. Yet the question of how precisely the Pythia produced her oracles—whether she spoke in intelligible words or simply uttered incoherent sounds interpreted by priests—has long been debated.

For many years, scholars assumed that the Pythia was essentially a passive vessel, possessed by Apollo, muttering ecstatically while male “prophets” took her utterances and turned them into well-crafted verses. However, ancient testimony—from Herodotus and beyond—provides a strong case that the Pythia herself spoke clearly and composed her own oracles in verse. She may have used conventional formulas and somewhat rudimentary hexameters, but that does not invalidate her agency. In fact, attempts to bribe an oracle typically targeted the Pythia directly, rather than male priests. She evidently had control over the final “product.”

The Question of Verse and Authenticity

Some classical scholars once dismissed many of the transmitted Delphic oracles in hexameter as products of later fabrication. The presence of precise predictions—especially those that turned out to be correct—caused suspicion. Yet the Greeks themselves never questioned that the Pythia had the power to utter poetic prophecies. Moreover, oracles were often written down immediately by the inquirers or recorded in official archives (as at Sparta), reducing the likelihood of radical distortions.

Indeed, the surviving verse oracles frequently appear awkward, with inconsistent meter and jarring transitions in imagery. Such unpolished style makes little sense if professional poets had systematically “cleaned up” the language before release. It makes far more sense if the oracles were composed orally, under the pressure of possession, by a woman who otherwise lived outside the conventional realm of epic composition. Their rawness points to authenticity: the Pythia was producing verse on the spot, borrowing from a stock of epic formulas any Greek of her era would have absorbed through oral culture.

Ambiguity as a Randomizing Device

One hallmark of Delphic oracles is their ambiguity. Heraclitus famously said that the “Lord whose oracle is at Delphi neither speaks nor conceals but gives a sign.” The Pythia’s verse often contains puzzling grammar, multiple possible subjects, and metaphorical language. This ambiguity allowed the inquirer to frame and interpret the oracle in a way that suited his or her current dilemma, leaving room for various outcomes. Such “randomizing devices” (including cryptic verses, abrupt shifts, or even references to unrelated events) signaled the god’s involvement. They made it more difficult for either the questioner or the priestess to manipulate the response for personal gain, preserving the oracle’s reputation for impartiality.

Who Was the Pythia? Late Sources vs. Classical Reality

Most information about the Pythia’s personal background, age, and training comes from authors writing centuries after Delphi’s golden age. Plutarch (second century CE) wrote about Delphi in his Moralia essays, claiming that the Pythia in his time had to be over fifty years old, had once been married, and now lived a secluded, chaste life. Diodorus Siculus (first century BCE) stated that originally the Delphic priestess was a young maiden, but after a disturbing episode of rape by an inquirer, the Delphians changed the regulations.

Scholars today often treat these statements as reflecting earlier, “timeless” tradition, but Greek religion was far from static. Delphi’s prime extended roughly from the eighth century to the fourth century BCE; Plutarch was writing some four hundred years after the classical period. His observations likely do not capture conditions during the fifth century BCE, when oracular influence peaked. Aeschylus, for instance, opens the Eumenides with a Pythia who describes herself as an old woman heading into the adyton. But even in that portrayal, she is in clear control of the process and personally welcomes inquirers to the shrine, suggesting her role was far from a silent puppet.

The Problem of “No Training”

Ancient (and some modern) commentators sometimes insisted that the Pythia was an uneducated peasant, ensuring that her prophecies could only come from Apollo, not from learned artifice. But if we set aside rhetorical claims, evidence suggests a more plausible reality: the Pythia probably underwent significant preparation. She was immersed in a tradition that included exposure to epic formulas, Delphic religious practices, and possibly older priestesses who guided her. This may not have resembled formal “schooling,” but, in a preliterate or semi-literate oral culture, religious apprenticeship could be a highly effective means of gaining expertise.

The Pythia’s eventual absence of polished Homeric diction in some oracles can also be explained by the ecstatic nature of her task. Composing verse oracles on the spot, in a state of trance, understandably produced lines that might seem less “finished” than epic poetry practiced by professional bards.

Assyrian Prophetesses and Tibetan Oracles

The idea of women standing as mouthpieces for a god was not unique to Greece. In ancient Assyria, between the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, oracles dedicated to the goddess Istar of Arbela were regularly recorded and sent to the king. Many were delivered by female prophets in an altered state of consciousness. Their compositions, while employing repeated motifs of reassurance (“Do not be afraid!”), show that these women were steeped in religious and literary tradition. They produced part-prose, part-poetry communications that the royal administration took seriously enough to archive.

A much more recent parallel comes from Tibetan Buddhism. The Chief State Oracle of Tibet—historically a male figure—enters a deep trance induced by ritual stimuli (incense, prayer, chanting). While possessed by a protective spirit, he may produce strikingly poetic messages on the spot. Observers note that some oracles are more eloquent than others, consistent with the fact that each oracle’s composition depends on the personality and background of the medium as well as the nature of the spirit.

Such cross-cultural parallels suggest a human capacity to enter trancelike states and deliver messages with literary or poetic qualities—even if they diverge from standard discourse. They also show that oracular roles can confer substantial social authority, regardless of gender, precisely because the speaker is understood to be channeling a deity.

The Power and Dangers of Spirit Possession

Despite the prestige that might come from offering divine counsel, there were also risks. Plutarch’s essay The Decline of Oracles recounts a troubling incident in which a Pythia was coerced to prophesy when the sacrificial omens were unfavorable. She reluctantly went into the adyton and began shrieking before collapsing. She died a few days later. The text describes her “hysterical” behavior and the subsequent terror of those witnessing it. While this is a late anecdote, it does indicate that forced or ill-prepared consultations were considered dangerous—and that the Pythia was not a mere ventriloquist dummy. If she was unwilling or in the wrong frame of mind, tragedy could ensue.

Even in Aeschylus’s Eumenides, the Pythia prays for success before starting her day’s oracular duties, hinting at the stress and vulnerability that accompanied possession by Apollo. She wanted things to go well, partly for the sake of her own wellbeing—another detail that supports the notion that this was a real person making direct contact with something she (and the rest of Greece) believed to be a divine force.

Cassandra and Diotima

Literature provides vivid (if dramatized) windows into female seers. Cassandra in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon is a Trojan princess cursed by Apollo so that no one believes her. The tragedy spotlights her “prophetic garb” and the heartbreak of seeing calamity while remaining powerless to persuade. Her speech is raw and staccato, reminiscent of oracular utterances that repeat certain images and pivot abruptly between time frames. Although Cassandra’s tragedy is that she is disbelieved, the drama recognizes her extraordinary powers of insight.

Plato’s Diotima is a different type of prophetess altogether: she appears in the Symposium as a philosophical teacher revealing the ladder of love and the nature of beauty. Plato says she “delayed the plague at Athens by ten years,” explicitly calling her a seer with apotropaic powers. Whether she existed historically or not, the portrayal testifies that an Athenian audience could imagine a female seer instructing even the likes of Socrates.

In short, such literary depictions, though not strictly historical, reflect a cultural comfort with the idea of inspired women speaking divine truths—comfort enough that these characters could resonate with spectators and readers. While tragedy often sets these figures on a collision course with authority, comedy and philosophical texts could represent them as matter-of-fact and even revered.

Ambiguity, Agency, and the Role of Female Seers in Society

The significance of women’s involvement in divination cannot be reduced simply to “they spoke on behalf of a god and men listened.” The ambiguous and elusive nature of oracles created space for a female voice to command attention in a fundamentally patriarchal context. Because the prophetess was understood to be channeling a deity’s mind, her gender was overridden by Apollo’s supreme voice—or by the healing or purification power of whichever deity she served. This was paradoxically both empowering and potentially restrictive: empowering because, in the moment of consultation, she occupied a central role in matters of state, warfare, or private life; restrictive because her authority was publicly acknowledged only while she was perceived as “possessed” or “transmitting” divine will.

Nevertheless, evidence of bribery cases (like that of Periallus at Delphi) shows that contemporaries viewed the Pythia’s judgments as crucial; otherwise, bribes would not have mattered. The same dynamic emerges in other Greek oracles, such as the priestesses at Dodona, whom Herodotus interviewed regarding the sanctuary’s mythical origins. He specifically names them—Promeneia, Timarete, and Nicandra—as key informants, crediting them with a sophisticated explanation of how the oracle began. He treats their words as authoritative enough to cite in his Histories. The fact that they were women is never remarked upon by Herodotus as a problem; on the contrary, they stand out as the main spokespeople for the site’s tradition.

Despite patriarchal norms, then, Greek religious practice carved out important public and private roles for seers of both genders. The domestic sphere of purification, healing, and personal guidance was probably even more open to women, for it was less documented by official historians. Yet, even in major pan-Hellenic contexts like Delphi, a female figure rose to preeminence as the mantis par excellence.

Case Study: The Oracles of 481 BCE

A striking example of a female seer’s direct influence on major political events occurs in Herodotus’s account of the Persian invasion under Xerxes (480–479 BCE). In the run-up to that crisis, the Spartans, Argives, and Athenians each sought counsel at Delphi. Herodotus preserves several oracles delivered to them—likely in a relatively short window of time. The verse is often clumsy, jumping erratically in grammar and mixing references to burning temples, bleeding statues, or unstoppable armies. The oracles are also ambiguous in a practical sense: for example, they predict that Sparta will either lose a king or see its entire city destroyed, but do not make it crystal-clear which enemy is the direct threat.

Scholars who argue these oracles were invented after the fact must contend with their rough, unpolished form, which scarcely feels like a grand poetic fabrication. It is more plausible that a single Pythia—named Aristonice, according to Herodotus—delivered them. Each prophecy is replete with abrupt metaphors and archaic formulaic expressions reminiscent of Homeric or epic speech but arranged in a manner that can only be called awkward. Far from diminishing their significance, these stylistic oddities lend credence to the notion of spontaneous oral composition. They also demonstrate how an individual woman, in the role of the Pythia, shaped the narratives and decisions of entire city-states on the brink of war.

Conclusion

The figure of the female seer stands at the intersection of faith, politics, and cultural practice in ancient Greece. From the shadowy mythic lines of Manto and Daphne, to the traveling healers and purification experts, to the revered priestesses of Delphi and Dodona, the evidence strongly suggests that women occupied significant positions within the mantic tradition. They were not merely accidental exceptions nor mere mediums whose words were automatically “corrected” by men. Instead, they operated as recognized authorities, whether diagnosing a household’s spiritual ills, safeguarding a community through purification rites, or dictating the fates of entire city-states from an oracular tripod.

The role of the Pythia is the most dramatic example of female religious authority. Despite attempts—ancient and modern—to minimize her agency by portraying her as uneducated or purely passive, the available sources, combined with cross-cultural parallels, paint a richer picture. She likely underwent a significant process of apprenticeship within the Delphic sanctuary, absorbing epic language and oracular traditions. During her sessions, she combined extemporaneous verse composition with ambiguous phrasing, defying simple interpretation and ensuring the oracle’s reputation for impartial and divine judgment.

Seen from the broader perspective, female seers were an accepted part of the Greek religious landscape, especially in contexts removed from the well-documented sphere of warfare. The stele from Mantinea and references to a seer named Satyra, among others, confirm that divinatory arts were not limited to men. And while Greek tragedies sometimes depict seer-priestesses like Cassandra in states of social conflict, the historical record reveals that many such women were integral to their communities. Indeed, none other than Herodotus sought the opinions of priestesses at Dodona and recounted them with respect, indicating how female oracular voices could be seen as entirely legitimate authorities.