Europe’s Precarious Rise and the Onslaught of the Black Death

When the Black Death arrived on the European mainland, it did so at a historical crossroads

The fourteenth-century calamity that history remembers as the Black Death did not happen in a vacuum. Long before the bubonic plague devastated the continent, Europe had been riding an upswing of economic and cultural development, only to face intermittent crises ranging from natural disasters to bitter political rivalries. When the Black Death arrived, it found a continent already teetering and dealt it an unprecedented blow.

This post explores the conditions in Europe before and during the plague years, focusing especially on how Italy—home to vibrant city-states and a long tradition of trade—was particularly hard hit by this mortal pestilence.

Europe Before the Plague: Growth and Tensions

From roughly the twelfth century onward, Europe entered a phase of sustained economic expansion. A confluence of events and broader political circumstances—such as the Crusades—had spurred unprecedented change. In part, the call to arms against Muslim powers in the Holy Land had removed some of Europe’s more quarrelsome elements and shifted the focus to expanding trade routes and financial networks. With fewer large-scale conflicts on home soil, agriculture, commerce, and learning advanced.

A Booming Population

One core catalyst for economic and cultural flourishing was population growth. Where earlier centuries had been marked by invasions, internal strife, and generally sparse populations, the high and late Middle Ages witnessed considerable demographic recovery. The result was more land being brought under cultivation, more bustling towns, and a slow but steady rise in living standards for many people.

- Land and rent values: Lands in certain regions, like the Rhine and Moselle valleys, increased dramatically in worth; the same plots that had little worth in the tenth century became immensely valuable by the thirteenth.

- Urbanization: By 1300, more land was under the plow than at any prior point in recorded history. Cities also burgeoned. Towns that might once have held only a few thousand residents now boasted tens of thousands.

- Growing literacy and learning: Universities sprang up across Europe, with Paris leading the way in advanced learning. Scholars took interest in translations of Arab intellectuals like Avicenna and Averroes, newly rendered from Arabic into Latin. This influx of knowledge ignited developments in architecture, mathematics (such as Fibonacci’s double-entry bookkeeping), and even music, where polyphony began to replace older forms of plainchant.

Signs of Strain

Yet demographic and economic booms inevitably run up against environmental and social limits. By the end of the thirteenth century, Europe was showing cracks under its own growth:

- Agricultural exhaustion: Intensive farming methods had stripped the soil of nutrients in many areas, especially where fallow cycles were not well-observed.

- Climate disruptions and famines: Europe experienced a series of harvest failures—famines struck England in 1272, 1277, 1283, 1292, and 1311. Between 1315 and 1322, heavy autumn rains created a “Great Famine,” as constant wet conditions prevented both harvest and adequate salt production for preserving meat.

- Soaring prices, malnutrition, and social unrest: During these repeated famines, the price of grain soared; the poor resorted to desperate measures such as eating dogs, cats, or even human flesh. As supply chains strained, towns and cities revealed how vulnerable they were to food shortages.

Alongside these hardships, the wide-scale peace that had prevailed during the height of the Crusades began to fracture. The papacy’s move to Avignon (1309–1376), inter-state rivalries, and the early rumbles of what would become the Hundred Years’ War all contributed to instability. By the early 1340s, Europe was on shaky economic and political ground—just in time for the arrival of plague.

The Black Death Arrives in Mainland Italy

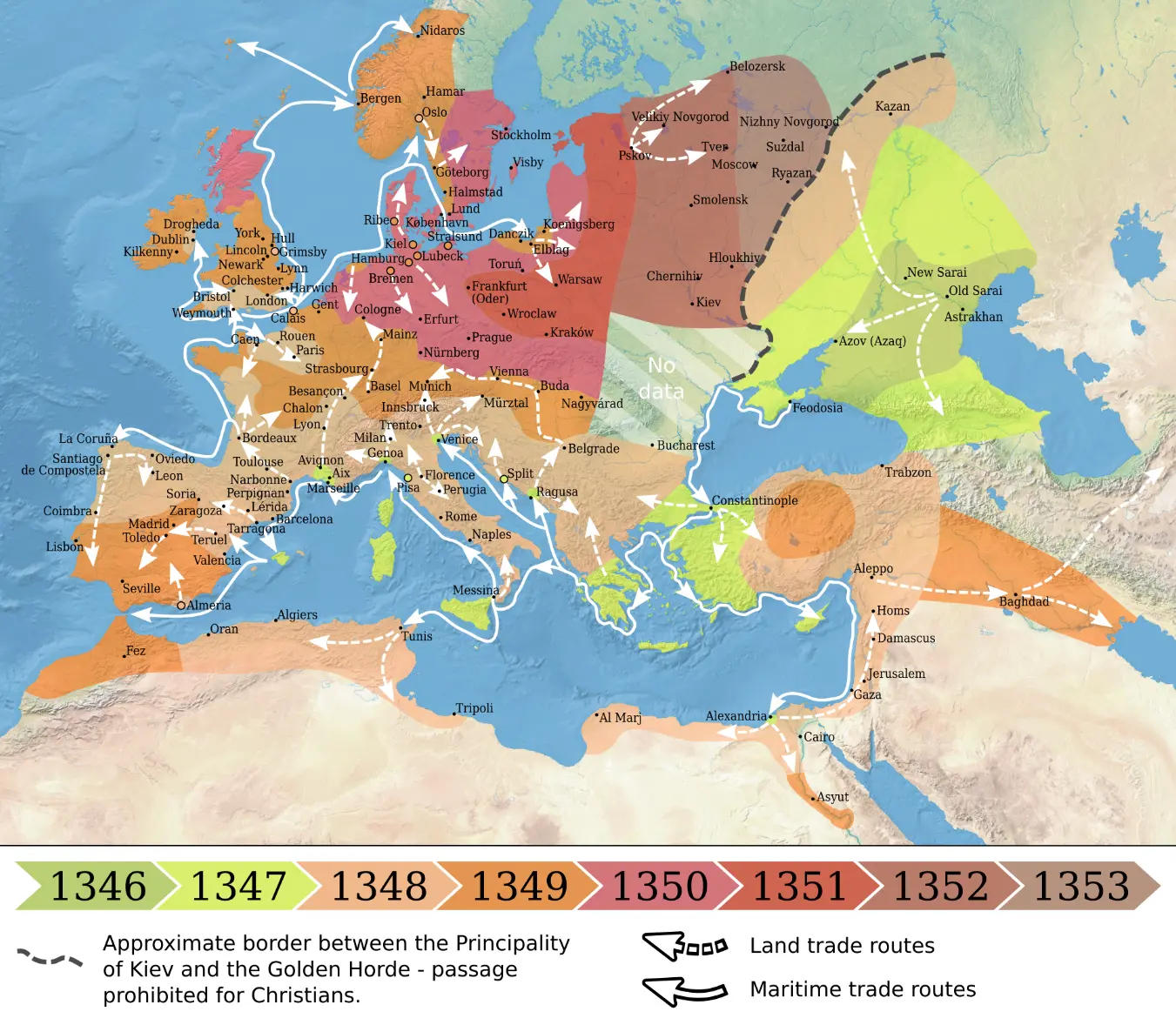

By early 1348, the Black Death had already established a terrible foothold in Sicily, entering through the port of Messina in late 1347. As galleys sailed north and west, carrying sick and dying sailors, Italian coastal cities found themselves in the path of this new scourge.

For many Italians, the plague’s appearance was a terrifying confirmation of God’s wrath. Gabriel de Mussis, a chronicler of the period, wrote of “the scale of the mortality” and how it seemed as if the Day of Judgment had come. The immediate backdrop of natural disasters, from earthquakes to repeated harvest failures, reinforced the idea that all the forces of nature—and of heaven—were conspiring against them.

A Litany of Calamities

Italy was already suffering multiple crises:

- Earthquakes: Major quakes had rattled Rome, Pisa, Bologna, Padua, Venice, and Naples in the years preceding the plague.

- Crop failures: Throughout 1345, heavy rainfall lasted nearly six months, causing abysmal harvests. In 1346 and 1347, food shortages in many Italian regions forced people to subsist on grass, weeds, or meager rations of bread (when it was even available).

- Economic woes: The enormous Florentine banking houses—the Peruzzi, the Acciaiuoli, and the Bardi—collapsed between 1343 and 1345, each losing spectacular sums of money. Employment dried up in once-thriving sectors, compounding the misery of famine.

Politically, the Italian peninsula was no less volatile. The Guelphs and Ghibellines, two opposing factions often at war over papal versus imperial influence, continued to clash. Noble houses like the Orsini battled the Colonna. Genoa and Venice vied for maritime supremacy and quarreled over trade routes. Amid such disunity, few organized efforts could address a deadly, fast-spreading contagion that respected neither wealth nor social standing.

Repelled Ships, Too-Late Measures

When plague-bearing ships from the East sought refuge at ports like Genoa and Venice, city authorities tried to turn them away, launching burning arrows or other projectiles at the vessels. However, time and again, these preventative moves came too late. Plague had already come ashore:

- Genoa and Venice: Both seaports had strong mercantile connections with the Black Sea and beyond, forming key gateways for goods—and, tragically, for plague-laden fleas clinging to rats and cloths.

- Flight of infected ships: Vessels denied entry would simply move on, seeking another harbor. Unwittingly, they spread the disease to multiple coastal towns, including those in southern France and the Balearic Islands.

By early 1348, the Black Death had arrived in mainland Italy and began its disastrous inland journey.

The Plague in Florence: Boccaccio’s Testament

Florence was one of the richest and most populous cities of Europe. It was also particularly vulnerable to contagion, given its dense population, thriving textile industries, and heavy trade traffic. When the Black Death struck in 1348, its devastation was so acute that some historians refer to the initial Italian outbreak as the “Plague of Florence.”

Boccaccio’s Eye-Witness Introduction

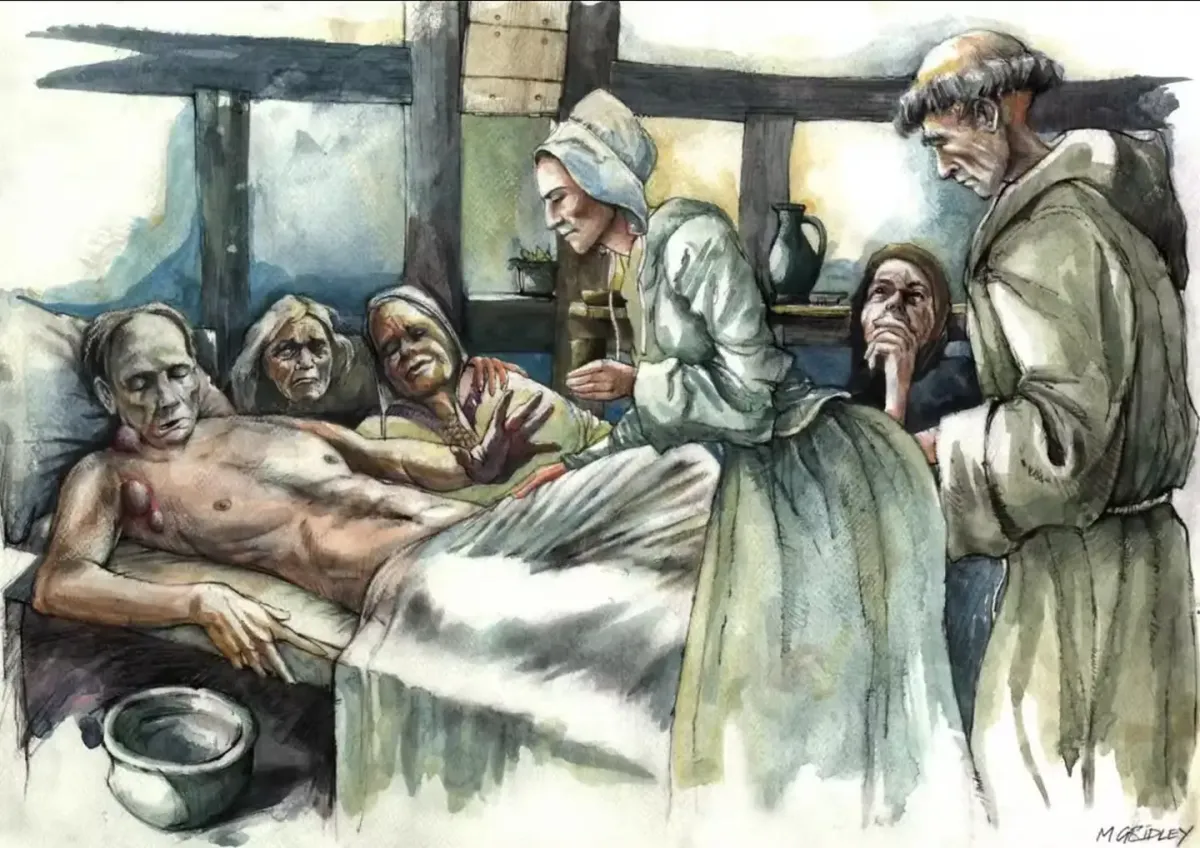

Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron is one of the most famous literary works to describe the Black Death’s horrors. He dedicates the opening of the book to portray in raw detail how swiftly the plague overtook the city. He describes:

- Terrifying symptoms: Tumors in the groin or armpits, sometimes the size of apples, coupled with black or livid spots on the skin. Many died within three days, often lacking any other classical sign of illness like prolonged fever.

- Rapid contagion: According to Boccaccio, even speaking with or touching the clothing of the afflicted could spread infection. Although this is not precisely how bubonic plague transmits, it certainly felt that way to frightened Florentines facing a mysterious disease.

- Societal collapse: Boccaccio paints a city in full disarray. Relatives refused to care for their own sick. Many died alone in their homes, with no funerals and minimal burial rites. Family, social, and even religious customs broke down under the weight of fear.

He goes on to relay grim stories: swine collapsing after chewing on a plague victim’s discarded clothing, or individuals fleeing the city entirely for country villas, pursuing pleasure and revelry in hopes of outlasting the chaos. Meanwhile, countless urban poor died by the hour, left with meager or no care.

Sheer Numbers and Possible Overstatement

Boccaccio claims that 100,000 Florentines died within a few months. While modern estimates suggest the actual figure was closer to half that, his broad point stands: the toll was massive, and survivors struggled to make sense of it. Even with possible embellishments—pigs dropping dead on the spot, or talk of supernatural apparitions—Florentine chronicles consistently confirm that the city was forever changed.

Abandonment and Crime

Desperate times spawned desperate acts. Criminals, such as the becchini (often translated as “grave-diggers”), would threaten people with the possibility of spreading contagion if they were not paid off. They might also demand vastly inflated fees for removing corpses or burying loved ones, creating pockets of opportunistic profiteering amid public panic.

While the plague initially impacted urban populations more severely—due to crowding and poor sanitation—it soon spread to the countryside, often following individuals seeking refuge. Tuscan villages suffered as badly as the city itself; entire hamlets lay abandoned, with domestic animals left to roam through untended fields. For many farmers, flight was simply not possible, meaning rural families perished in place, untended and unnoticed.

The Plague in Other Italian Cities

Florence was only the beginning. Across Italy, from north to south, the Black Death followed trade routes and country roads with relentless momentum. Each community attempted its own measures—sometimes systematic, other times haphazard—to contain or at least mitigate the lethal effects.

Venice: Land of Quarantines and Funeral Barges

Few places had such extensive maritime networks as Venice. Because the city thrived on commerce, it was exceptionally vulnerable:

- Mass mortality: Chronicles note 600 deaths per day at the epidemic’s height.

- Emergency burial sites: The Doge, Andrea Dandolo, convened the Great Council to designate new burial locations at St. Erasmo in the Lido and at St. Marco Boccacalme. Endless fleets of funeral barges transported coffins across the Venetian lagoon, filling these sites at alarming speed.

- Forty-day quarantine: Venice famously introduced the concept of a “quarantena,” a 40-day isolation for travelers arriving from plague-affected regions. This approach—guided partly by religious tradition—did become an influential measure across Europe, though in 1348 it was still rudimentary.

- Collapse of social structures: Like everywhere else, doctors and priests quickly succumbed, and many survivors with means fled. The city was left with a skeletal workforce, often forced to ignore standard civic duties.

Milan: Brutal Containment

According to some accounts, Milan, under the leadership of its Visconti rulers, implemented extreme tactics: if a household showed signs of plague, the authorities sometimes walled the family inside, alive. Though possibly apocryphal or exaggerated, such stories underscore the draconian measures some city-states took, especially when faced with an illness they could neither control nor understand.

Pistoia: A More Documented Response

Unlike many places, Pistoia left behind clear civic records of its efforts to manage the outbreak:

- Bans on travel and trade: As soon as plague arose in nearby Pisa, Pistoia forbade travel to or from that city. Initially, no outside goods—especially corpses—were permitted.

- Quarantine for funerals: Funerals were to be limited strictly to family members; the usual tolling of bells or public announcements were forbidden to minimize large gatherings.

- Adjusting measures: These ordinances shifted as the epidemic progressed; when it became clear that plague was already within city walls, some rules—like bans on travel—became irrelevant. Nevertheless, Pistoia tried to maintain an official structure, appointing specific grave-diggers, regulating the disposal of bodies, and ordering the removal of animal waste from streets.

Orvieto: Silence and Neglect

In stark contrast, Orvieto’s city council took almost no early action. When they met in March 1348, only about 80 miles separated Orvieto from the plague-ridden Florence. Yet the record shows no urgent ordinances:

- Weak medical infrastructure: The town had just one dedicated doctor and one surgeon, supplemented by a handful of learned citizens who might assist occasionally. Private hospitals and charitable institutions were inadequate for a population of roughly 12,000.

- Plague hits hard: Within three months, half the residents died. Council members either perished or fled, leaving no one to enforce even the most basic health regulations. The city’s chief religious procession, the Assumption, was canceled entirely—an extraordinary measure in deeply devout medieval Europe.

Siena: Abandoned Cathedrals and Endless Funerals

Siena shared many of Florence’s problems: population density, lively trade, and powerful noble factions. When the Black Death arrived:

- Projects interrupted: Construction on Siena’s grand new cathedral halted mid-building, never to be fully completed as originally planned. The masons died, and no workers replaced them.

- Economic freeze: The wool industry, which had helped make Siena prosperous, collapsed. Imported goods dried up; prices for local staples soared.

- Church wealth, public despair: The Church, ironically, grew wealthier through the surge of bequests and donations made by the dying seeking spiritual redemption. Meanwhile, the city’s coffers were nearly empty for public works.

- Personal testimonies: Agnolo di Tura wrote movingly of the mass graves and the heartbreak of burying his own five children by himself. He described dogs dragging corpses from shallow pits, a ghastly visual that symbolized the utter breakdown of social norms.

Piacenza, Bobbio, and Other Towns

Across northern Italy, smaller towns fared no better. Gabriel de Mussis, a notary from Piacenza, recorded horror stories:

- Sudden contagion: Merchants would enter a town like Bobbio, sell their goods, then die with the unlucky buyer and the buyer’s entire family.

- Consecrated ground shortages: Churches ran out of burial space, forcing bodies to be piled in plazas or newly dug trenches, sometimes in layers with thin coverings of soil.

In Piacenza itself, coffins were carried through the streets day after day, funeral rites condensed to a shadow of their usual solemnity. Priests and gravediggers demanded higher pay for their services, if they hadn’t already been felled by disease. Everywhere, the spectacle was the same: panic, flight (if possible), or grim resignation for those left behind.

Mortal Pestilences and Harsh Realities

Looking at the overall picture, the Italy of 1348 was a land of stark contradictions. Only decades earlier, it had seemed poised to continue its economic and cultural ascendancy. Wealthy merchant families, flourishing banks, and robust trades in luxury textiles all suggested an empire of commerce at the height of its powers. In a matter of months, the Black Death upended these visions of prosperity.

- Pre-Existing Vulnerabilities: Famine, soil exhaustion, bankruptcies, and natural disasters had already worn down the resilience of urban and rural communities alike.

- Lack of Coordinated Response: While some civic authorities (like those in Pistoia or Venice) attempted systematic quarantines or burial rules, others (like Orvieto) did practically nothing in time. Even well-intentioned measures proved ineffective against a disease no one fully understood.

- Social Fragmentation: Fear drove families to abandon each other; entire social rituals—funerals, weddings, religious festivals—were suspended. Crime spiked, as opportunists exploited chaos. Faith in longstanding institutions, both church and civic, began to erode.

- Psychological Toll: Chronicles overflow with supernatural omens, from sword-wielding dogs to apocalyptic pronouncements of divine judgment. In an era accustomed to seeing life events through a religious lens, the plague seemed like the wrath of God made manifest.

That devastation would not remain confined to Italy. As the diseased ships moved on or as travelers escaped inland, similar stories repeated themselves in France, Iberia, England, and then throughout Germany, Scandinavia, and beyond. Historians debate specific mortality rates, but nearly all agree on the broad scope: the Black Death may have killed between one-third and one-half of Europe’s population within just a few years.

Conclusion

When the Black Death arrived on the European mainland, it did so at a historical crossroads. Despite the twelfth-century renaissance in learning and the thirteenth-century leaps in trade and urban growth, by the early fourteenth century Europe had slid into food crises, economic downturns, and renewed political feuds. These fault lines became lethal conduits for plague.

In Italy—one of the most prosperous and densely settled regions—the plague’s impact was particularly vivid and widely documented. Chronicles from Florence, Siena, Venice, and smaller centers show the same tragic arc: from initial shock and denial to a harrowing acceptance that no social class, no city wall, and no measure of wealth could keep the Black Death at bay. Town councils enacted quarantines, built new cemeteries, and pleaded for divine intervention, but to little avail. Disease, panic, and hunger ravaged the land.

Even from the ruins, however, glimpses of survival and adaptation emerged. Cities like Venice refined quarantine policies that would influence public health for centuries. Communities that survived slowly rebuilt, sometimes forging new social contracts in the process. Much as the plague decimated labor forces, it also spurred transformations in agriculture and wages, helped shape cultural responses to mortality, and contributed to shifts in religious devotion and authority.

Yet for those living through 1348, it must have felt like the end of the world. Mortal pestilences, financial ruin, and political upheavals coalesced into a maelstrom of death and despair. The Decameron’s recounting of Florentines escaping the city to tell stories is a poignant reflection of a society grasping for any semblance of normalcy in the midst of horror. Stripped of communal bonds and facing daily funerals on a scale no one had witnessed before, Italy stood at the threshold of a new era—a tragic inflection point where the hope of past centuries collided with a merciless new disease.