Columbus’s Lost Letters and the Malaria Puzzle

If the colonists truly caught malaria at La Isabela, it would imply the parasite arrived with them.

In 1985, a Spanish bookseller astonished historians by announcing the discovery of nine letters and reports attributed to Cristóbal Colón (Christopher Columbus). Seven of these texts were said to be previously unknown: copies of letters and reports from all four of his American voyages. As news spread, scholars worldwide buzzed with excitement—could they reveal new insights into the man credited with inaugurating Europe’s permanent presence in the Americas? To everyone’s surprise, two respected scholars of the admiral’s writings, Consuelo Varela and Juan Gil, cautiously examined the manuscripts and pronounced them authentic (albeit later-era copies). The Spanish government quickly bought the documents, releasing a facsimile edition in 1989, followed nine years later by an English translation.

At first glance, historians found nothing “spectacular” in these new letters—no shocking detail that significantly rewrote Columbus’s biography. Yet one passage leapt out to a handful of attentive readers. In the text describing events at La Isabela, Spain’s first permanent base in the Americas, Columbus mentioned his men suffering from something called ciciones, describing their pattern of chills and fever. Translators and later scholars, including Noble David Cook, interpreted ciciones as “tertian fever,” an old term for malaria’s cyclical bouts of sickness. If that reading is accurate, Columbus’s words mark one of the earliest recorded hints that malaria—a disease unknown in the pre-Columbian Western Hemisphere—may have arrived with Europeans soon after 1492. Could the very founder of this transatlantic link have inadvertently documented one of history’s most consequential disease introductions?

Below, we explore how a single puzzling word from a recovered letter helped spotlight malaria’s cataclysmic presence in the Americas. In doing so, we see how malaria shaped the fate of American colonies, abetted slavery, affected war outcomes, and ultimately left marks still visible centuries later.

The Striking Discovery: A Word Called Ciciones

In the Columbus text from his second voyage (1493–1496), the admiral writes that his men “all realized it rained a lot” at the site of La Isabela, and that they fell gravely ill from what he labels ciciones. At first glance, the Spanish words for malaria—paludismo or fiebre terciana—are not used. Instead, we have this uncommon term. Meanwhile, Columbus speculates that native women around La Isabela might somehow have spread it, prompting him to suspect a venereal condition. Nothing in the letter clarifies the specific symptoms.

Modern dictionaries offer no help with ciciones, and even eighteenth-century sources skip over it. Yet a 1611 dictionary of Spanish defines a similarly spelled term, ciçiones, as fevers that begin with chills, “attributed to the cold mistral wind.” Another authoritative dictionary from 1726–1739 suggests that the word more likely meant “tertian fever,” an old European label for malaria’s hallmark: fever spikes and chills every other day in a 48-hour cycle (day of fever, day of quiet, day of fever, and so on). Linking ciciones to malaria, as Noble David Cook and others have done, is therefore plausible—though not ironclad proof. Historical diagnoses are notoriously uncertain, and many illnesses once fell under broad categories like “intermittent fever.”

If the colonists truly caught malaria at La Isabela, it would imply the parasite arrived with them. Malaria is transmitted by certain Anopheles mosquitoes that pick up microscopic parasites (species of Plasmodium) from infected humans and pass them on. Because the disease was already endemic in late fifteenth-century Spain, it is no stretch to imagine one or more sailors carrying a latent strain. One infected mosquito bite in Hispaniola could set off a chain reaction. Even so, the question remains murky. Columbus and his contemporaries lacked the concept of “germ theory”; they lumped many ailments under imprecise categories.

Regardless, the ciciones puzzle points us toward a bigger picture: malaria’s post-1492 spread and its decisive impact on both Native and European societies. It was one dimension of a wider “Columbian Exchange” of organisms that would transform the planet’s ecology, agriculture, and diseases.

Malaria and the Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange was historian Alfred W. Crosby’s term for the enormous global swap of plants, animals, and microbes that followed 1492. Food items like maize, tomatoes, and potatoes traveled east to Europe, Africa, and Asia, while wheat, rice, cattle, horses, and many diseases traveled west. Among the latter were smallpox, influenza, and possibly malaria—none of which had been established in the pre-contact Americas (there is debate about a preexisting monkey malaria, but certainly not the human variants). If malaria arrived around Columbus’s time, it joined diseases like smallpox in creating havoc among Indigenous peoples. Yet unlike smallpox, which caused swift, terrifying epidemics that then subsided, malaria became endemic, a year-to-year presence that gnawed at communities in areas with warm temperatures and the right mosquitoes.

Malaria remains a major killer worldwide. Today it infects around 225 million people annually and causes upward of three-quarters of a million deaths—overwhelmingly young children in tropical regions. Historically, it played an immense role as well. Regions plagued by mosquito-borne illnesses saw stunted economic growth and social dislocation. Where repeated outbreaks swept in, many inhabitants withdrew from prime farmland, and newcomers (particularly Europeans) often died at astonishing rates. From the colonial era onward, malaria and its cousin disease yellow fever drastically influenced where settlers dared to go, whom they chose as laborers, and how societies developed.

England’s Marshes and the Virginia Connection

Before investigating how malaria shaped colonies like La Isabela or Jamestown, it helps to glance at England—paradoxically also a place with pockets of malaria. Although Plasmodium falciparum (the more dangerous species) struggles to survive in cooler climates, Plasmodium vivax can persist in milder zones. In southeastern England from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, a major marsh-draining push created brackish pools ideal for Anopheles mosquitoes. Coastal counties such as Essex, Kent, and Sussex saw decades of “fever and ague.” Historical accounts describe high mortality rates, with many so ill they could scarcely farm. This environment became known for “marsh fever,” or “intermittent fevers,” terms widely understood by Elizabethan and Stuart England.

Thus, when the Virginia Company recruited colonists for Jamestown in 1607, many prospective emigrants (often from London or other low-lying areas) may have carried dormant vivax parasites. They disembarked along the James River, where swamps, brackish water, and abundant mosquitoes created perfect conditions for malaria to spread. Jamestown’s colonists were famously beset by hunger and poor leadership. But the “laziness” and “listlessness” recorded by frustrated leaders could well have stemmed from repeated malarial bouts. By 1657, the governor of Connecticut, John Winthrop, was already noting “tertian fever” cases in his colony, implying the parasite had traveled well north.

Over time, colonists learned to survive. If they weathered the first infections—what locals called their “seasoning”—they gradually developed partial immunity. But new arrivals, especially poor indentured servants, often died within the first year, leaving labor shortages in tobacco fields. Inevitably, the search for reliable labor pushed plantation owners to examine alternatives like slaves. But that dynamic emerged even more forcefully in Carolina and the Caribbean, thanks in part to the deadlier falciparum species, which often traveled along with enslaved Africans brought over in large numbers.

Malaria, Slavery, and Economic Choices

Slavery existed in many societies, yet it became distinctive in the Americas, especially the English colonies south of the Mason-Dixon line. Understanding why requires acknowledging malaria’s role. As the staple crops in regions like Virginia and Carolina—tobacco and later rice—demanded intensive year-round labor, planters initially relied on indentured servants from Europe. However, malaria ravaged these Europeans, who lacked immunity. Moreover, indentured servants were contracted for just a few years, so even survivors might soon depart to start their own small farms.

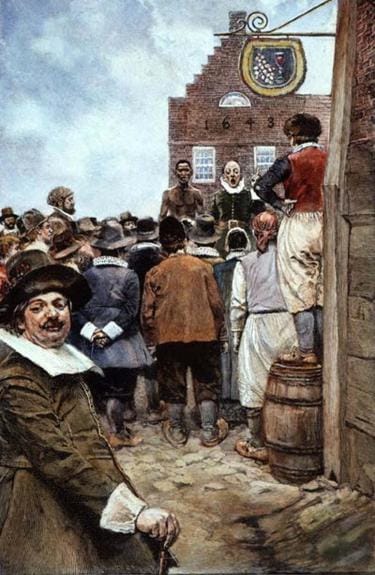

Africans, by contrast, brought genetic and acquired protections. One is “Duffy negativity,” which blocks Plasmodium vivax from entering red blood cells. Another partial immunity is the sickle-cell trait, which impedes falciparum (though at a painful cost). Collectively, people from West and Central Africa tended to survive malaria more often than Europeans did. Enslavers noticed, however dimly, that Africans survived the dangerous planting seasons more reliably—thus, despite higher purchase costs, slave owners ended up better off in malarial zones. Brutal logic steered planters to prefer African captives over European servants or Native enslaved laborers. Over decades, this advantage underpinned the expansion of chattel slavery into a region anchored by plantation agriculture, creating an enduring social and economic order.

Contrast this with cooler parts of North America, like New England, where fewer mosquitoes meant fewer malarial outbreaks. Without the same deadly environment for European workers, indentured servitude remained more practical, and although slavery did exist (Massachusetts officially sanctioned it in 1641), it was never the defining labor system. In short, malaria was not the only cause of southern slavery, but it strengthened the case for using enslaved Africans, deeply shaping colonization patterns and forging a grim legacy that persisted into the American Civil War and beyond.

The Caribbean Cauldron: Sugar, Mosquitoes, and Yellow Fever

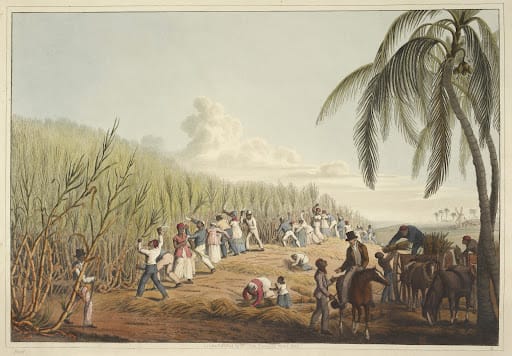

Nowhere was the impact of mosquito-borne disease more overt than in the Caribbean sugar islands. By the mid-seventeenth century, English colonists on Barbados (and soon neighboring islands like Nevis, St. Kitts, and Antigua) discovered that sugarcane, originally from Asia, thrived in tropical soils. The global craving for sugar soared. But sugar extraction required grueling labor: cutting cane under the scorching sun, boiling juice in giant cauldrons, and stoking enormous fires to refine the product. Planters clamored for workers—whether indentured Europeans or enslaved Africans.

A second deadly parasite entered the picture: yellow fever, carried by the African mosquito Aedes aegypti. The virus rarely kills African children, who typically gain lifelong immunity. But unseasoned European adults newly arrived in the Caribbean are extremely vulnerable. The “seasoning” in the islands often meant a coin toss between survival and death by “black vomit.” Early on, Aedes aegypti found ideal breeding grounds in sugar pots left around plantations, the water they collected turning into lethal mosquito nurseries. Repeated yellow fever outbreaks decimated white newcomers and further tipped the labor scales toward relying on African captives. So extreme were the mortality rates for Europeans that few dreamed of establishing large-scale settler communities. Instead, absentee owners or small white managerial classes oversaw masses of enslaved Africans, forging what became known as “extractive states” with little impetus for local institutions or egalitarian growth.

Between malaria on the mainland and yellow fever in the Caribbean, African enslaved labor became the backbone of English, French, Spanish, and Dutch sugar economies. The profits were massive and financed merchant houses in Europe—but the cost in human suffering was unimaginable.

Malaria’s Invisible Hand in Warfare and History

Beyond labor and economics, malaria repeatedly influenced the outcome of wars in the Americas. One dramatic case: the American Revolutionary War. When British generals adopted a “southern strategy” in 1780, they marched armies into the Carolinas, unaware they were heading into the heart of P. falciparum territory. The region’s British loyalists tended to be seasonally immune—having grown up there—but the main body of British regulars, fresh from the Isles, quickly fell ill. By the time of Yorktown, General Cornwallis’s ranks had been reduced by disease to such an extent that they could hardly resist General Washington’s combined French and American forces. The surrender at Yorktown effectively secured U.S. independence.

Later, during the American Civil War (1861–1865), Union troops crossing into Confederate states faced repeated fevers each summer and fall. Malaria by itself did not determine every battle, but it drained Northern manpower at critical junctures, forced generals to slow offensives, and ensured high non-combat mortality. Historians note that more Union soldiers died from disease than Confederate bullets. Meanwhile, many Southern soldiers—already exposed in childhood—had partial resistance. Malaria’s grip on the conflict arguably prolonged the war, pushing the Lincoln administration toward more radical steps, including the Emancipation Proclamation.

From these episodes to the attempts of French colonists in South America (such as Guyane) or Scottish explorers in Panama (whose disastrous Darien scheme in 1698 lost thousands to “fevers”), malaria repeatedly knocked invaders off balance, curtailed grand imperial ventures, and shaped entire national outcomes.

Echoes of Ciciones: The Ongoing Legacy

In the end, whether Columbus’s men truly contracted malaria at La Isabela may never be conclusively proven. But that puzzle leads us to a broader story: how a single mosquito-borne parasite insinuated itself into lands from Virginia’s wetlands to Caribbean cane fields, from the Amazon to West Africa itself. Many of the historical developments we take for granted—the thrust of plantation slavery in the American South, the limited white settlement in certain tropical regions, the outcomes of military campaigns—can be traced in part to this disease’s relentless, hidden force.

For Indigenous peoples, malaria joined smallpox, influenza, and other traumas brought by outsiders, thinning populations and undermining polities. Meanwhile, it distorted colonial economics. Planters and governments, desperate for resilience in mosquito-ridden zones, funneled ever-larger numbers of enslaved Africans into lethal labor systems. Over time, these structures hardened into what some economists call “extractive states,” systematically preventing local growth and perpetuating huge inequalities.

Today, modern medical science can diagnose malaria accurately, and treatments ranging from quinine to newer drugs have helped reduce its toll. Worldwide campaigns have aimed to curb mosquito breeding and distribute protective nets. Yet even today, the disease remains entrenched in many developing regions—its annual death toll and stifling economic drag an echo of centuries-old patterns. History reminds us that whenever humans create or neglect standing water, transform forests into farmland, or pack ships with desperate people, they inadvertently shape nature’s rhythms. Microbes and mosquitoes seize openings we do not foresee.

From the vantage point of the 21st century, the ciciones line in Columbus’s recovered letter stands as more than a linguistic oddity. It represents an early clue that Old World parasites were quietly embedding themselves into New World ecosystems. Beyond the global voyages of conquerors, beyond the drama of gold lust or missionary zeal, these tiny organisms stowed away, rewriting the destiny of millions in ways unseen at the time. Whether the admiral’s men first saw malaria at La Isabela or not, the disease became inextricably tied to the story of the Americas—marking the complex, often tragic reality of the Columbian Exchange.

Malaria’s far-reaching influence can be found in plantation architecture (houses built on hills, with broad open lawns to discourage mosquitoes), in the presence of African diaspora populations across the hemisphere, and in countless political decisions that changed entire nations. So the next time we consider the legacies of 1492, we might think beyond ships, swords, or even smallpox. A single mosquito species hovering in tropical dusk, bearing a Plasmodium parasite, had as profound an impact as any conquistador or king—an impact captured faintly, but perhaps first, by one cryptic reference in Columbus’s “lost” letter.