Causes on Athens’ Oligarchic Revolution of 411 BC

The old guard of Athens—whose democracy had withstood numerous challenges—responded with resilience, reestablishing broader participation

Below is a discussion of the factors and personalities that converged to spark the oligarchic revolution in Athens in 411 BC—a sudden upheaval that temporarily ended democracy in the midst of the long Peloponnesian War. We will explore how the sociopolitical context of the 420s BC, the influence of sophists, and the mindset of a new generation of educated aristocrats created the conditions for this historic moment. Although the revolution ultimately failed, the ideas and ambitions of these younger Athenians illuminate a vital theme in fifth-century Greek history: how a restless and highly trained elite can transform political theory into real—and sometimes dire—political change.

The Oligarchic Revolution of 411 BC

During the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), Athens endured extraordinary pressures, culminating in the catastrophic defeat of the Sicilian Expedition in 413 BC. Two years later, against a backdrop of widespread fear and resentment, a small group of men seized power, establishing an oligarchy often referred to as “the Four Hundred.” Although the new regime lasted only about four months, this was Athens’ only major break from its relatively stable democracy between 508 and 322 BC.

When we say “the Four Hundred,” we are really referring to a small coterie—some scholars speculate that no more than fifty men actively orchestrated the move. Others joined or supported it once it was a fait accompli. This group shattered the democratic system created by Kleisthenes in 508 BC, later enhanced by Ephialtes around 462 BC, and molded under the guidance of Pericles. Athens had grown used to a democracy that functioned so effectively that even nominally aristocratic politicians operated within its framework. So how did a democratic city, after nearly a century of relative internal peace, succumb to oligarchy? The answers begin decades earlier, with a generation of young elites who grew to maturity in the 420s BC.

The Younger Elite: Between Democracy and Discontent

A War-Torn Background

Athenian youths born circa the mid-fifth century BC (roughly 455–445 BC) came of age during the Archidamian phase of the Peloponnesian War (431–421 BC). By then, Athens had been democratic for decades. Pericles, though aristocratic by birth, had governed as a champion of the people. The result was that democracy was rarely questioned in any fundamental way. Despite critics labeling certain leaders “demagogues,” no major figure before the 420s openly proposed a return to oligarchy. Accepting democracy was simply the natural political posture in Athens.

Yet for the younger members of the upper class—men who never knew an Athens without full democracy—there was an undercurrent of dissatisfaction. They recognized that democracy had embedded itself so profoundly that overtly challenging it was futile. If older aristocrats in the 460s still bemoaned the loss of Areopagos authority, the younger set in the 420s faced a system that seemed too established to overturn. Their democracy flourished, and the empire still brought in wealth. Many were bored, or at best unenthused, by mainstream democratic politics.

An Absence of Grand Causes

Unlike the generation that fought to limit the old Areopagos council or the one that had championed the Persian Wars, the 420s produced few galvanizing principles or moral imperatives around which young aristocrats could rally. The big questions— “Should we keep the empire?” “Should we remain democratic?”—were settled. The empire existed and was profitable; democracy functioned with minimal direct challenge.

In effect, their dissatisfaction was personal rather than systemic. They disliked demagogues who rose from middle- or even relatively modest families and seized influence. Figures like Kleon appeared in comedic plays as coarse or unrefined. Upper-class youths felt intellectually and socially superior, but they could not simply dismiss the “new men” because the democracy gave these up-and-coming leaders real authority. For the traditional elite, such developments stung, even if the new politicians were not as lowborn as caricatures suggested. Yet on the ground, Athens prospered. Younger aristocrats therefore found themselves with an unspoken frustration in search of a true political expression—and for many, this frustration centered on the “demagogues,” not on democracy’s theoretical foundations.

Aristophanes, the “Old Oligarch,” and the Young Elite Mindset

Aristophanes’ Comedic Critique

A window onto the mindset of this young aristocratic cohort appears in the plays of Aristophanes, himself part of that generation. In Knights (424 BC), he lampoons Kleon under the guise of the character “Paphlagon,” depicting a manipulative demagogue dominating an old figure named “Demos,” symbolizing the Athenian people. The comedic conceit is that only someone even more vulgar—a mere sausage-seller—can defeat Kleon. The play’s chorus, composed of Knights, vents frustration at how easily the people are swayed. Yet the democracy is depicted as something permanent; Aristophanes does not advocate overthrowing it. Instead, he implies that the political reality is so entrenched that only comedic fantasy can dislodge these populist figures.

In Wasps (422 BC), Aristophanes pokes similar fun at the generation gap. Young aristocratic types scorn the older men who serve obsessively as jurors and cling to old-fashioned democratic rites. Tensions between father and son, old and young, reveal how democratic energies remain strong among older citizens, while well-born youths eye everything cynically, seeking an outlet for their intellectual frustration. None of these comedic critiques, however, suggests that democracy is fragile. If anything, the comedic lens shows its vigor.

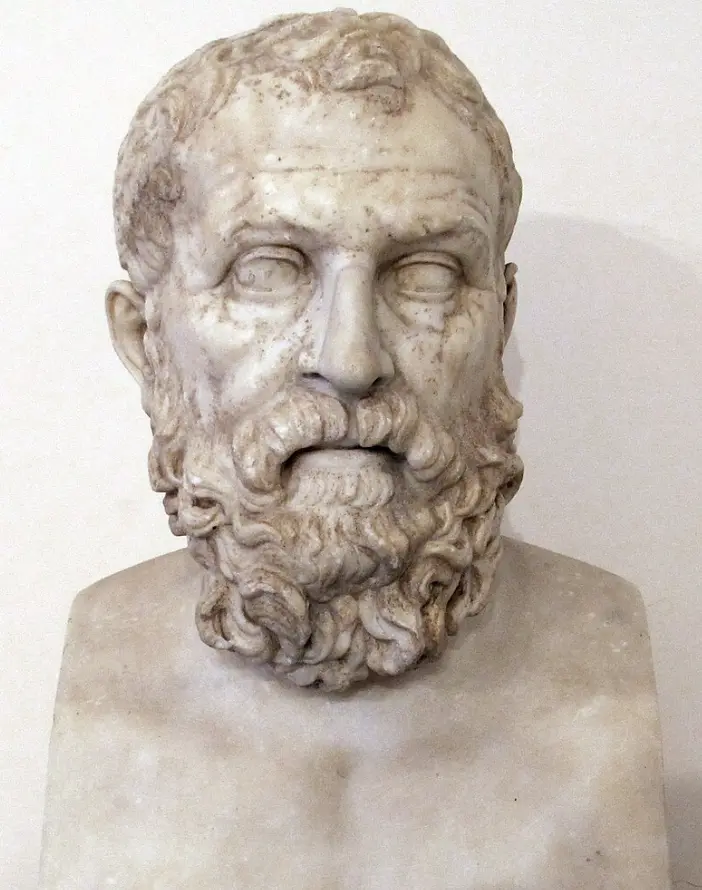

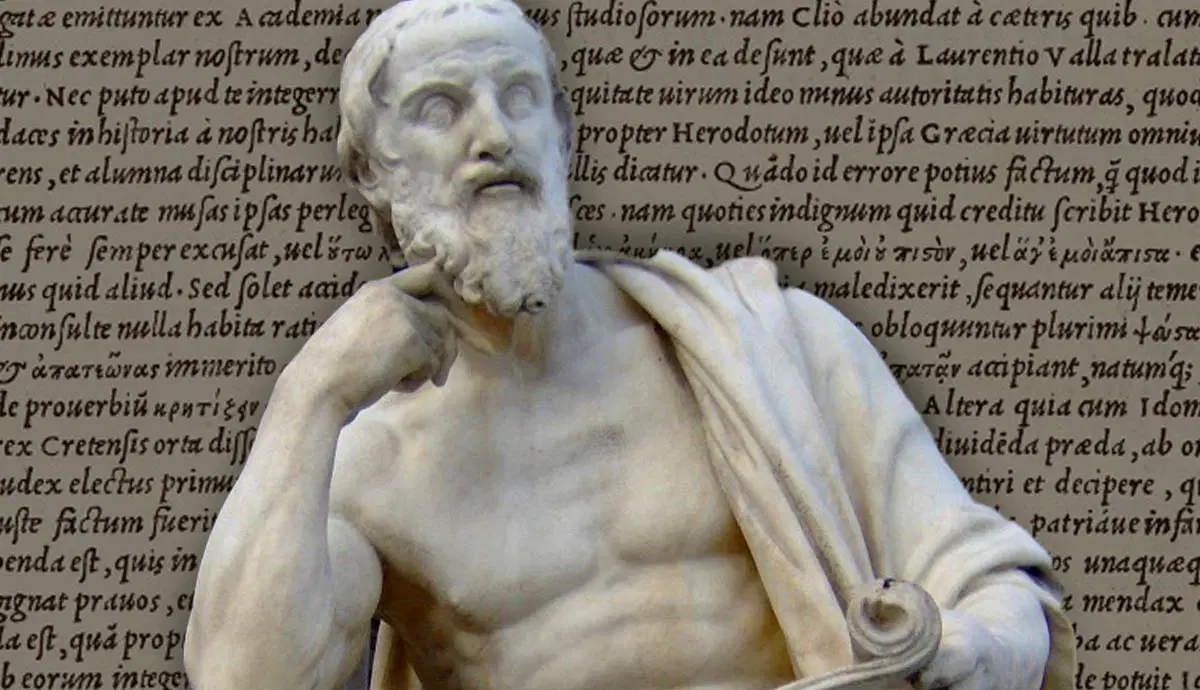

The Pseudo-Xenophon (Old Oligarch) Treatise

An even more striking document from the same mid-century context is the so-called Athenaion Politeia attributed to “the Old Oligarch” (also known as Ps.-Xenophon). Scholars debate its author and date, but it is widely seen as emerging sometime in the later 430s or 420s. It reads like an intellectual exercise rather than a practical political pamphlet. The anonymous writer systematically defends Athens’ democracy—not because he loves democracy, but because, in his view, it perfectly serves the self-interest of the demos (the people). He despises the demos personally, but he concedes that the system works in their favor by providing wages, imperial profits, and full participation.

In effect, this “Old Oligarch” ironically justifies democracy by accepting that each group has a right to look after its own advantage. The Athenian people use the empire’s revenues to sustain public pay (misthophoria) and festivals. Sea power guarantees that the lower classes, who row the triremes, remain politically dominant. The writer is resigned—there can be no shift away from democracy so long as the navy and empire survive. This conclusion lines up neatly with Aristophanes’ comedic logic: democracy is so embedded that the only truly radical threat would be if the conditions enabling the demos’ advantage (i.e., naval and economic power) were destroyed.

Influence of the Sophists

Both the Knights and the Old Oligarch reflect another factor binding the 420s generation: the sophists. Sophists such as Gorgias taught the art of rhetoric, enabling bright, ambitious youths to learn persuasive speaking and theoretical argumentation. Plato’s Gorgias famously depicts how this instruction can nurture dangerous personalities (like Kallikles)—men enthralled by power, adept at oratory, and committed to personal ambition rather than civic principle. Many aristocratic youths studied with sophists to outmaneuver so-called demagogues in popular assemblies, but they ended up with rhetorical skills ungrounded in moral commitments.

A crucial outcome of sophistic teaching was a preference for “ideal constitutions” and theoretical state-building. Since they had limited real scope to upend democracy in the stable decades of the 420s, they indulged in speculative thinking about how governments ought to be. These mental exercises produced small treatises, “lecture notes,” or speeches about reconfiguring councils, making the Areopagos more powerful, or limiting the role of the masses. For years, these ideas remained in the realm of the classroom or closed discussion circles—until circumstances changed drastically after the defeat in Sicily.

The Shock of Sicily and the Turn Toward Oligarchy

The Athenian disaster in Sicily (413 BC) was seismic. The city lost a significant portion of its fleet and manpower. Overnight, the assumptions propping up democracy—the secure flow of imperial revenues, the might of the navy—were thrown into question. The young aristocratic men, who once believed democracy was unshakable, realized conditions had shifted. The empire looked fragile, the treasury was depleted, and the momentum might swing toward any new system promising salvation.

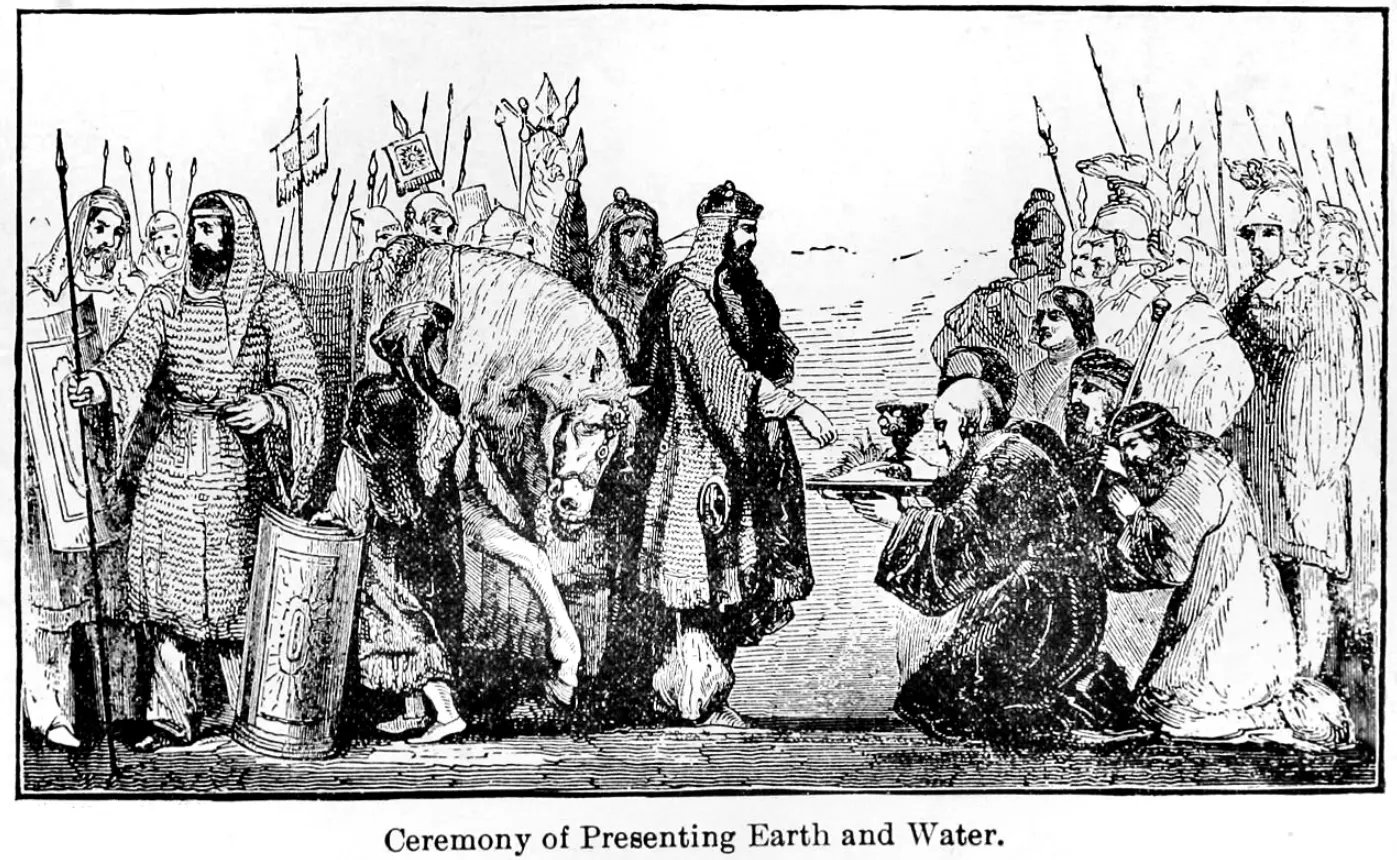

Another motivating factor was the possibility that Persia might join forces with Athens—if Athens abandoned its fully democratic ways. There was a rumor or assumption that the Persian satraps would only negotiate with an oligarchic Athens. Suddenly, the theoretical oligarchic models from lecture notes gained practical relevance. Men who had been merely dabbling in alternative constitutions or playing at being demagogues (because democracy was the only game in town) now switched to championing oligarchy, citing both the city’s dire condition and the prospect of Persian gold.

Key figures of this generation—Alkibiades, Phrynichos, Peisander—had once operated within democracy. After all, as Alkibiades famously noted, “We had no choice but to lead the people under democracy, for that was the reigning form of government.” But with the collapse of the naval power, they pivoted to push for rule by a narrow elite. The rhetorical skill they had honed and the theoretical fantasies they had nurtured found expression in practical conspiracies.

The resulting oligarchic regime of 411 was short and chaotic—often described as run by “the Four Hundred,” but perhaps fewer men truly drove events. They attempted to dissolve or drastically curtail democratic institutions, tried to cut off “unnecessary” expenses such as public pay, and expected the populace to acquiesce because the old formula—rowers expecting steady naval wages—no longer held. Unfortunately for them, they misunderstood that many ordinary Athenians embraced democracy for reasons beyond immediate profit. While fear gave the conspirators a temporary advantage, the city’s democratic reflex was still strong. Soon enough, the people rejected the Four Hundred, reestablished broader governance, and found ways to hold the city together.

Why the Coup Failed—and Why It Mattered

Crucially, the conspirators had operated under a cynical assumption: the masses only cared about material gain (misthoi). Destroy that, and the system collapses. In truth, ordinary Athenians would fight for their political voice even without economic windfalls. Indeed, from 411 to 404 BC, the city managed (for a time) to build fresh triremes and carry on the war under an essentially restored democracy, albeit one shaken by internal suspicion.

For the oligarchs, however, the events of 411 were the logical (if extreme) culmination of a mindset developed over many years: they had never valued democracy on principle but accepted it as the best route to personal or aristocratic success. The moment they believed democracy no longer served city survival—or their own ambitions—they substituted their theoretical constructs. What had been purely academic or rhetorical now manifested as lethal political action.

The partial failure of the Four Hundred underscores that training in rhetoric and abstract political models can be double-edged. On one side, it can produce comedic plays or treatises that cleverly dissect democracy’s flaws. On the other, in crisis, the same rhetorical tradition can rally men behind illusions of “perfect oligarchy,” ignoring how real Athenians might react.

This phenomenon highlights the stark generational dynamic in the mid-to-late fifth century BC. Figures such as Kleon or Hyperbolos emerged from different social strata yet found ways to align with the people’s genuine desire for a strong, participatory city-state. The young elites, shaped by sophistic methods, believed they were smarter and more “moderate” (often invoking terms like sophrosyne, self-control). But ironically, their hasty revolution in 411 displayed a lack of pragmatic caution. They overreached in dismissing the innate loyalty many Athenians still felt for democracy.

Lessons for Political Understanding

Critics of Athenian democracy sometimes reduce its challenges to a story of moral decline, from the “golden age” of Pericles to the manipulative populists of later decades. In truth, the democracy functioned robustly for about a century (508–411 BC) except for this brief oligarchic interlude. The real danger came not from the supposed gullibility of the people, but from a cadre of ambitious aristocrats who could not see beyond their own designs. Demos, in comedic caricatures, might appear foolish, but collectively the Athenians were surprisingly adept at judging and ultimately rejecting political experiments that served only a tiny elite.

After the Four Hundred collapsed, Athens’ democracy endured until 404 BC when it faced a second crisis in the aftermath of total defeat by Sparta. There again, oligarchic conspirators—this time the “Thirty Tyrants”—relied on class-based alliances, though with more brutality. The cycle of infiltration by men with partial philosophical visions repeated. Figures like Socrates, who personally did not conspire against democracy, nonetheless fell under suspicion for training or influencing men such as Kritias. Plato, shocked by the brutality of oligarchs he once might have considered intellectual peers, embarked on a deeper philosophical quest, eventually producing the Republic. The tension between philosophical idealism and practical governance echoes across these decades.

If we leap forward in time, we see that the universal challenge of bridging generational or ideological gaps remains. In some ages, youth movements can be conservative or reactionary—witness the aristocratic youths of 411 BC. In others, they may be radical left-wing forces trying to dismantle perceived injustices. In both cases, there are often misunderstandings, or even a refusal on each side to grasp the other’s true motivations. The Athenian crisis in 411 BC sprang from precisely such misreading: the conspirators assumed the people would yield, and the people could not believe certain youths would truly dismantle the constitution.

This dynamic is a warning to modern observers that bridging ideological divides requires genuine effort to see beyond stereotypes. Although the conspirators of 411 styled themselves as enlightened or prudent, they never recognized the democratic impulse that had taken root among ordinary Athenians. Without such understanding, they botched the revolution and unleashed chaos instead of stability.

Reading more:

Conclusion

The oligarchic revolution of 411 BC was not merely an opportunistic power-grab. It was the product of a decade-long intellectual current among an ambitious generation. Raised in an Athens that seemed unassailably democratic and wealthy, these young men learned the arts of sophistry and rhetorical theory, developing elaborate fantasies of how an ideal state might be arranged. They played along with democracy until the Sicilian catastrophe revealed a plausible moment to implement their theories.

The old guard of Athens—whose democracy had withstood numerous challenges—responded with resilience, reestablishing broader participation. Ultimately, the city persisted under democratic institutions for several more years, thereby proving that everyday Athenians had motives beyond mere profit when defending the political system. Their loyalty to democracy also underscored the perils of an intellectual class that mistakes a theoretical blueprint for a workable reality. Because the conspirators themselves were “too clever to understand,” they underestimated the deeper roots of the democracy they sought to replace.

That miscalculation is the central story of the revolution of 411 BC: how a handful of skilled, clever men, lacking genuine moral commitment to the community’s ideals, lost touch with the real bonds between ordinary Athenians and their hard-won political rights. The city’s eventual return to democracy after the Four Hundred fell is testimony to the resilience of a population that valued not just wages from empire, but the dignity and voice guaranteed by democratic governance.

From a broader standpoint, the 411 experiment highlights a timeless insight: while political theories can inspire bold plans, real communities often cling to inherited frameworks of participation and freedom in ways intellectual elites may not foresee. Far from being a dull acceptance of the status quo, Athens’ defense of democracy in 411 BC became one of the most striking testaments to the deep convictions that can animate ordinary citizens—even against conspirators who believed they were destined to rule.