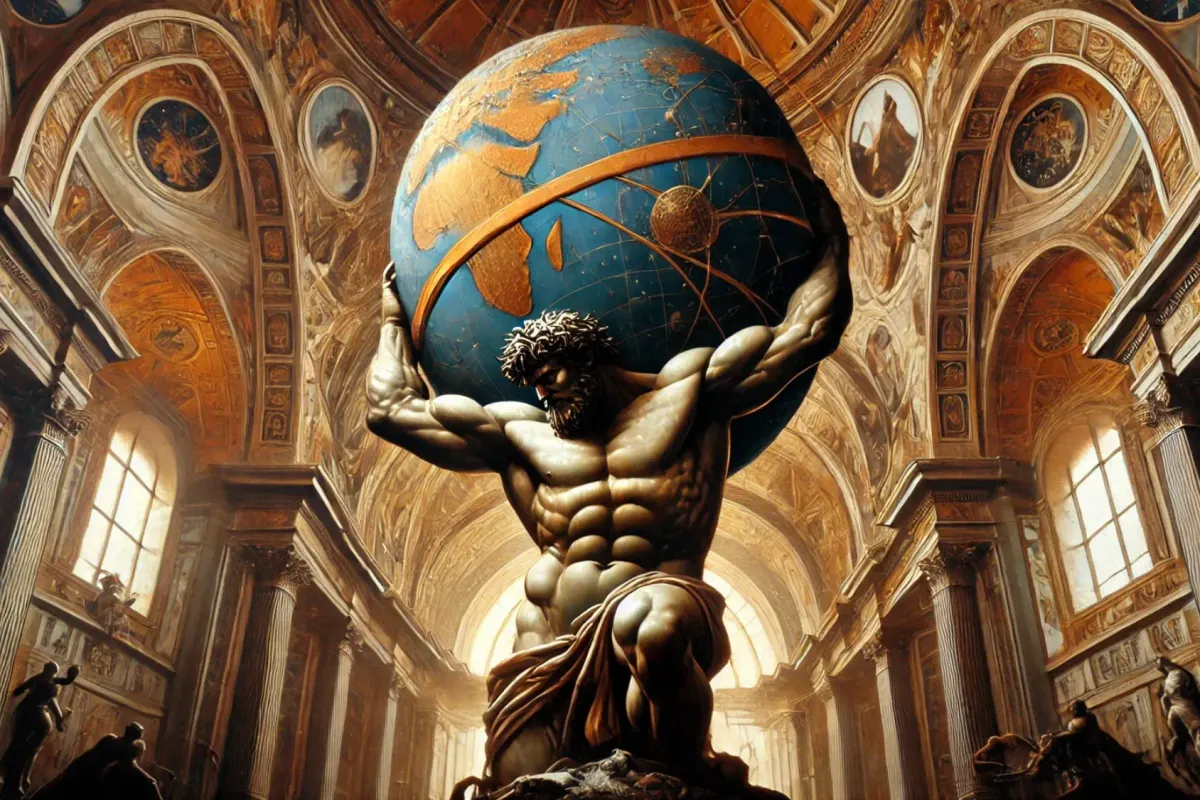

Atlas: The Titan's Burden

Because of fighting against Zeus in the Titanomachy, Atlas is punished to hold up the universe forever

Atlas, a prominent figure in Greek mythology, was the son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene (sometimes called Asia). He was a Titan, though this designation came later, as the term "Titan" initially referred specifically to the children of Uranus who overthrew him. Atlas had three notable brothers: Prometheus, the fire-bringer; Epimetheus, whose wife Pandora unleashed evils upon the world; and Menoetius, punished by Zeus for his role in the Titanomachy.

Atlas fathered many children, most notably with the Oceanid Pleione. Their seven daughters were the Pleiades, a star cluster, and included Taygete (mother of Lacedaemon by Zeus), Electra (mother of Dardanus by Zeus), Alcyone (lover of Poseidon), Celaeno (lover of Poseidon), Sterope (mother of Oinomaos by Ares), Maia (mother of Hermes by Zeus), and Merope (wife of the mortal Sisyphus).

His other five daughters by Pleione were the Hyades, who died of grief after their brother Hyas was killed and became a constellation. Atlas also fathered Calypso, who detained Odysseus, Dione, mother of Pelops, and the Hesperides, guardians of Hera's golden apples. The connection to celestial bodies solidified Atlas's association with astronomy.

The Titanomachy and its Aftermath

The Titanomachy, a ten-year war between the Titans and the Olympians, saw Atlas play a significant role. While Hesiod's Theogony briefly mentions his involvement, other sources, like Hyginus, claim he led the Titan forces. Nonnus's Dionysiaca describes the formidable threat Atlas posed, capable of shattering the heavens with hurled mountains.

In one account, Hera, angered by Zeus's infidelity, instigated the Titans, led by Atlas, to attack Olympus. They were defeated and cast into Tartarus. This story, however, conflicts with Hesiod's version, which places the Titanomachy before Zeus’s reign.

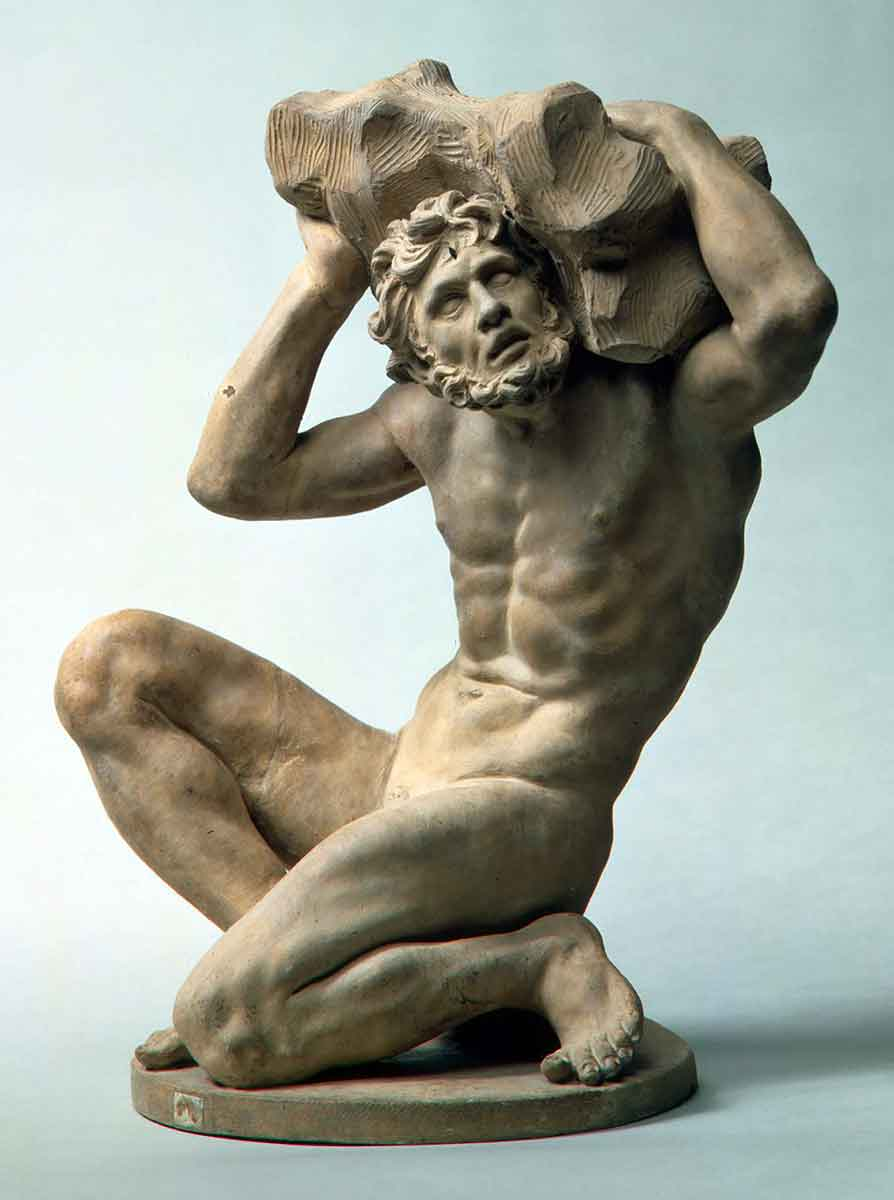

Bearing the Heavens

As punishment for his defiance, Atlas was condemned to hold up the heavens. Homer's Odyssey portrays him upholding the pillars of heaven, while Hesiod’s Theogony describes him carrying the celestial sphere on his shoulders. The shift from supporting pillars to carrying the entire sky signifies the evolution of cosmological understanding in ancient Greece.

The question remains: why was Atlas chosen for this task, considering the heavens were stable before the Titanomachy? Perhaps, as Nonnus suggests, Atlas’s transgression involved damaging the celestial supports during the war, necessitating his perpetual burden.

Heracles and the Golden Apples

One of Heracles's twelve labors involved retrieving the golden apples of the Hesperides. Following Prometheus's advice, Heracles offered to relieve Atlas of his burden temporarily while the Titan fetched the apples. Upon returning, Atlas, reluctant to resume his task, offered to deliver the apples himself. Heracles, cunningly, agreed but requested Atlas momentarily take back the sky so he could adjust his padding.

The Titan complied, and Heracles seized the apples and departed, leaving Atlas to his eternal burden. An alternative version of the myth bypasses Atlas entirely, with Heracles simply retrieving the apples himself after slaying the guardian dragon.

Perseus and the Stony Fate

Ovid's Metamorphoses presents a different fate for Atlas. Forewarned of a son of Zeus stealing his golden apples, Atlas built walls and placed a dragon to guard his garden. When Perseus, seeking rest, arrived, Atlas refused him entry, leading to a confrontation. Recognizing Atlas's superior strength, Perseus unveiled Medusa's head, turning the Titan to stone.

His body transformed into a mountain range—the Atlas Mountains—his hair and beard into forests, his shoulders into cliffs, and his hands into ridges. Thus, even in his petrified state, he continued to bear the weight of the heavens.

A More Earthly Account

Diodorus Siculus offers a more grounded version of the Atlas myth. Atlas, a shepherd from Hesperitis, owned sheep with golden fleece, often misinterpreted as golden apples. When pirates kidnapped his daughters, the Hesperides, Heracles rescued them. Grateful, Atlas gifted Heracles some sheep and taught him astrology. Because of his astronomical knowledge, Atlas was said to bear the heavens, a burden Heracles metaphorically assumed upon learning Atlas's celestial wisdom.

Legacy and Interpretation

The story of Atlas resonates through time, symbolizing endurance, resilience, and the weight of responsibility. The image of him bearing the heavens has become an iconic representation of strength and burden. Different versions of the myth reflect evolving interpretations of the cosmos and the role of gods and heroes.

From a leader of the Titans challenging Zeus to a shepherd sharing astronomical knowledge, Atlas's story reveals the multifaceted nature of Greek mythology and its enduring power to capture the human imagination.