Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia on the Rise of the Thirty Tyrants

Even after the oligarchic collapse, the notion of returning to a “pure,” original constitution remained powerful in Athenian political discourse.

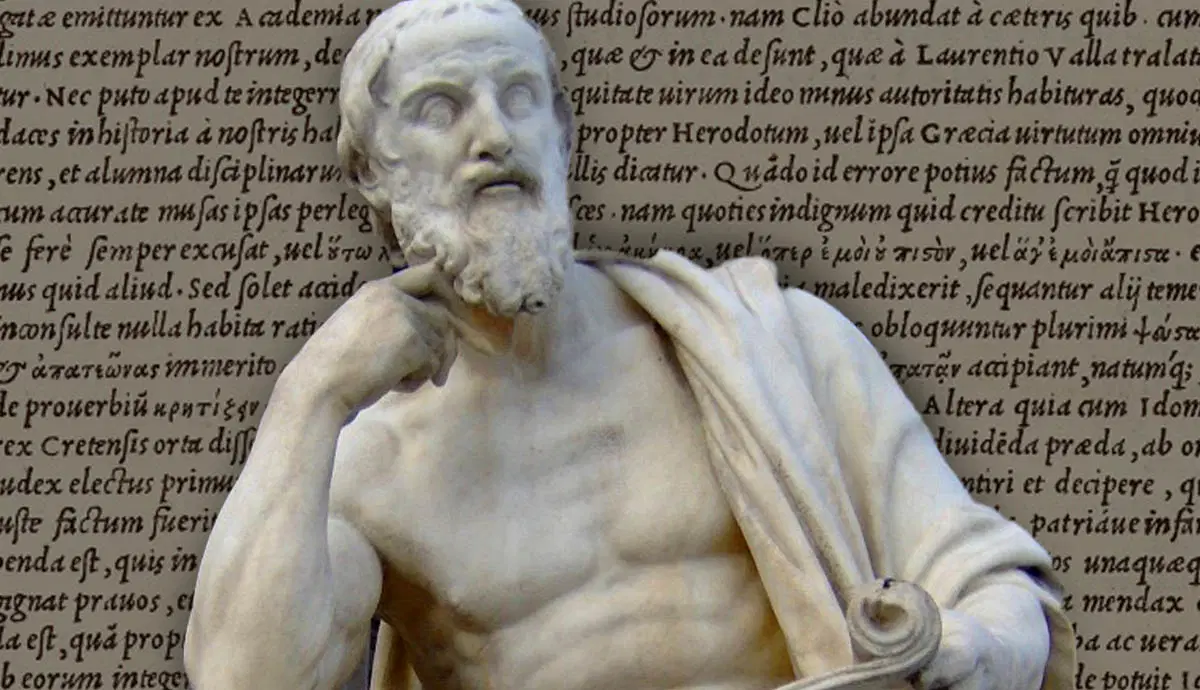

Few periods in Athenian history have generated as much debate and scrutiny as the final years of the fifth century BCE, a time when Athens suffered defeat in the Peloponnesian War and endured the brief but brutal regime of the Thirty Tyrants. Among the ancient sources that shed light on these tumultuous events is Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia (often translated as The Constitution of the Athenians). Ever since the modern publication of this work by F.G. Kenyon in 1891, scholars have contended with its implications for reconstructing the political narrative of late fifth-century Athens. In particular, Aristotle’s account of the transitional period between 413 and 403 BCE—including the establishment of the Thirty—has proven both illuminating and controversial.

In what follows, we will examine how Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia helps us understand the creation of the Thirty Tyrants, the context in which they came to power, and the political dynamics that influenced their short-lived rule. We will also compare Aristotle’s perspective with that of other ancient sources—such as Xenophon, Diodorus, Lysias, Andocides, and Plutarch—in order to explore whether Aristotle’s narrative should be taken as reliable evidence or dismissed as merely a partisan piece of historical writing.

The Athenaion Politeia and Its Sources

Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia comprises 69 chapters describing the history and form of the Athenian constitution. Modern scholars typically consider the latter portion (chapters 42–69) more historically reliable, as it provides more contemporary accounts of fourth-century Athenian government. However, the earlier chapters (1–41) have often been treated with suspicion, partly because they rely on sources about the archaic and classical periods that may be riddled with factual discrepancies or ideological biases.

Despite these reservations, dismissing the earlier chapters entirely risks losing valuable information not preserved elsewhere. Indeed, chapters 29–41, covering the critical period from 413 to 403 BCE, supply details that are absent or only partially covered in other extant sources. Aristotle’s discussion of the commission of thirty syngrapheis (law-drafters), his presentation of constitutional documents of the Four Hundred and the Five Thousand, and other significant moments (such as the events immediately preceding the establishment of the Thirty) are indispensable for any historian seeking to reconstruct the era.

Potential Influences on Aristotle

Critics have long debated the nature of Aristotle’s sources for the Athenaion Politeia. There is general agreement that he relied on:

- The poems of Solon

- Lists of archons

- Some form of public or private archives

- Fifth- and fourth-century historians and Atthidographers, possibly including Androtion

Beyond these general possibilities, numerous theories about anonymous pamphlets or pro-oligarchic documents abound. Some scholars have even posited that Aristotle might have copied a pro-Theramenes pamphlet. Yet such claims remain entirely speculative. We cannot definitively prove any single source for Aristotle’s account, and even if we could, there is no reason to assume that he merely copied it verbatim.

Aristotle’s political leanings may have led him to admire “moderate” politicians such as Nicias and Theramenes; however, this does not necessarily invalidate the basic factual content of his narrative. Political bias is unavoidable in most ancient writings, but unless we find direct proof of falsification, what Aristotle reports deserves careful consideration.

Other Ancient Sources on the Thirty

Xenophon and the Hellenica

Xenophon’s Hellenica (especially 2.2–2.3) is a key contemporary text on the last years of the Peloponnesian War and its aftermath. Xenophon focuses primarily on military and diplomatic events and, at times, seems either less informed or less interested in the fine details of Athenian domestic affairs. Consequently, he sometimes omits or glosses over internal Athenian politics that do not directly involve Spartan operations. Notably, Xenophon does not mention a clause in the peace treaty that required Athens to return to the “ancestral constitution” (patrios politeia). Nor does he exonerate Theramenes; rather, he depicts him in a way that allows various interpretations of his role.

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus (13.107 and 14.3–4) offers a continuous narrative of events but relies on sources like Ephorus, whose material can be selective or prone to moralizing. Interestingly, Diodorus does claim that the final treaty which ended the war specified that the Athenians would be governed under the patrios politeia (i.e., an ancestral or traditional constitution). This directly parallels Aristotle’s testimony in the Athenaion Politeia.

Lysias

The speeches of the orator Lysias—particularly Against Eratosthenes (12) and Against Agoratus (13)—are valuable for understanding the atmosphere of political recrimination after the restoration of democracy. Lysias was personally embittered by the actions of the Thirty, having suffered family losses. Not surprisingly, his account is partisan. Lysias tends to implicate Theramenes as deeply as possible, holding him responsible for the oligarchic takeover.

Andocides

In On the Peace (3), Andocides briefly references the events surrounding the Thirty Tyrants. Like Lysias, his perspective is partial and shaped by personal experiences of exile and the subsequent amnesty. Andocides does not reproduce the full text of the peace treaty, claiming only to cite what mattered for his immediate argument.

Plutarch

Plutarch’s Life of Lysander (14–15) details Spartan involvement in Athenian affairs. He cites a “decree of the ephors” that does not mention any patrios politeia clause. While this decree is valuable, it may differ from the final version of the peace agreement that the Athenian assembly actually ratified. Plutarch’s interest lies in character portraits and moral lessons, so his omissions or emphases might not reflect the full range of contemporaneous documents.

The Patrios Politeia Clause: Fact or Fiction?

One of the most hotly contested details about the settlement of 404 BCE is whether the Spartans really imposed a constitutional stipulation requiring that Athens be ruled according to the patrios politeia—literally, the “ancestral constitution.” Aristotle (Athenaion Politeia 34.2–3) and Diodorus (13.107) both affirm that such a clause existed. Yet Xenophon, Plutarch, and most other sources do not mention it.

Explaining the Omissions

- Xenophon: He rarely provides thorough coverage of internal Athenian politics. Moreover, his pro-Spartan sympathies might make him reluctant to record any promise that Sparta later disregarded.

- Plutarch: His quoted decree of the ephors may reflect an earlier or different stage of negotiation, rather than the final peace treaty.

- Lysias and Andocides: Both men quote only the aspects of the treaty that were relevant to their prosecutions or defenses. If the patrios politeia clause was not crucial to their specific rhetorical goals, they might have omitted it.

The Feasibility of Such a Clause

Why would Sparta, on the brink of total victory, concede any constitutional terms to Athens? It seems counterintuitive—yet not impossible. Athenian leaders like Theramenes likely stressed the importance of maintaining some form of self-government to secure popular consent to the treaty. Meanwhile, the Spartan commander Lysander, though influential, faced domestic political rivalry at home. King Pausanias and other conservative Spartans reportedly opposed Lysander’s ambitions to create a network of puppet decarchies across the Greek world. A formal clause committing Athens to a vague “ancestral constitution” may have seemed a workable compromise, especially if it prevented immediate chaos or long-term resentment within Athens.

If such a clause existed, it might have been ambiguous enough to appease all parties:

- Democrats could argue that the patrios politeia referred to a reversion to moderate or radical democracy.

- Oligarchs might insist that truly “ancestral” governance predated the radical democratization under Ephialtes and Pericles, thus paving the way for an oligarchic revival.

- Moderates like Theramenes favored a restricted democracy—perhaps recalling Solon or Cleisthenes—as a middle path.

Political Factions in Post-War Athens

The Three-Way Split (Aristotle’s Perspective)

In Athenaion Politeia 34.2–3, Aristotle sketches a tripartite division of Athenian political sympathies after the peace:

- Radical Democrats (dêmotikoi) who aimed to preserve full democracy.

- Oligarchs tied to influential clubs (hetairiai) and exiles, eager for a narrow oligarchy.

- Moderates, including Theramenes, Archinus, Anytus, Cleitophon, and Phormisius, who advocated the patrios politeia in the sense of a balanced or limited democracy.

Diodorus and the Two-Part Divide

Diodorus mentions only a dual split between oligarchs and democrats, with the patrios politeia effectively meaning democracy in the eyes of the larger group. Nonetheless, his description aligns with Aristotle on one critical point: most Athenians associated the “ancestral constitution” with democracy.

Subversive Maneuvers

Lysias provides one of the more vivid accounts of how oligarchic clubs maneuvered behind the scenes. He speaks of five “ephors”—an unofficial borrowing of Spartan terminology—set up within Athens to coordinate conspiracies against the democracy. These individuals allegedly manipulated the selection of key officials (like phylarchs) and orchestrated votes in the assembly to favor oligarchic aims. According to Lysias, these activities paved the way for what would later become the Thirty Tyrants.

The Controversial Assembly: Appointing the Thirty

Both Diodorus and Lysias describe a critical assembly in which Athens voted on whether to replace democracy with a new constitutional board of thirty men. According to Diodorus, the oligarchic faction invited Lysander to Athens from Samos to pressure the populace. Upon arrival, Lysander convened an assembly and proposed installing the Thirty to handle all affairs of state.

Theramenes openly objected, citing the patrios politeia clause in the treaty and denouncing the idea that the Athenians should give up their freedom. Lysander responded with threats, claiming that Athens had violated its obligations and that Spartan patience was exhausted. Undeterred, Lysander insisted the Athenians had no choice but to comply or face destruction.

Lysias, conversely, paints Theramenes as an active collaborator with Lysander. He claims Theramenes even manipulated the timing of the assembly so that Lysander’s forces could arrive at Athens without opposition. Moreover, Lysias accuses him of endorsing the proposed decree by Dracontides that installed the Thirty. According to Lysias, many citizens shouted their disapproval, but the threat of Spartan reprisal—or perhaps actual Spartan soldiers standing by—intimidated them into submission.

Interestingly, these accounts do not necessarily contradict each other. Theramenes might at first have resisted Lysander’s suggestion, only to realize that open defiance of Spartan power was futile. Alternatively, he might have tried to maintain a public persona of moderation while quietly conceding to oligarchic demands. In any event, the assembly voted for the creation of the Thirty. Despite strong opposition from the rank-and-file democrats, the measure carried. The Thirty Tyrants—among them Theramenes—took power, marking an abrupt termination of the democratic constitution.

Aftermath: The Short Reign of the Thirty

Having established the Thirty, Lysander departed Athens. The presence of men like Theramenes in the new government may have reassured some Athenians that an outright reign of terror would not ensue. Yet the coalition quickly revealed fractures. Extreme oligarchs—led by Critias—resorted to purges and executions of perceived enemies. Theramenes ultimately found these acts intolerable and challenged them, which led to his own prosecution and execution. Despite its moniker, the regime of the Thirty Tyrants was not monolithic.

As the Thirty alienated more and more Athenians, a resistance formed. Democratic exiles, led by Thrasybulus, seized the fortress at Phyle and then took the Piraeus. Eventually, King Pausanias—not Lysander—arranged peace terms that ended the oligarchy. Athens was allowed to restore its democracy, and the moderate or “ancestral” form of governance that Theramenes had once championed came into partial being. The city’s laws were codified anew, explicitly referencing governance kata ta patria—“according to the ancestral way.”

Conclusion

Aristotle’s Athenaion Politeia remains an essential, if challenging, source for the turbulent years surrounding the Thirty Tyrants. Its testimony on matters such as the patrios politeia clause and the tripartite division of political factions should neither be dismissed nor accepted blindly. Rather, it must be weighed alongside the accounts of Xenophon, Diodorus, Lysias, Andocides, and Plutarch.

Despite Aristotle’s apparent sympathy for moderate politicians—most notably Theramenes—his text offers details about Athenian internal politics that no other single ancient source provides. By comparing these narratives, a plausible reconstruction emerges: the patrios politeia clause in the 404 BCE peace treaty was indeed significant, though purposely vague. This ambiguity enabled each faction—democrats, oligarchs, and moderates—to argue for a form of government that suited its agenda. Ultimately, the Spartan general Lysander’s intervention, combined with Athenian fears of renewed war, facilitated the establishment of the Thirty. Yet the seeds of the regime’s downfall were sown from its inception, as differing conceptions of “ancestral government” clashed and tore the city apart.

Even after the oligarchic collapse, the notion of returning to a “pure,” original constitution remained powerful in Athenian political discourse. The final settlement under King Pausanias, and the subsequent restoration of a democratic but moderate government, was arguably closer to what Theramenes and other moderates had envisioned. In a sense, the Athenaion Politeia documents a broader historical phenomenon: appeals to ancestral tradition can serve as rallying cries for reform or revolution, uniting people with profoundly different political agendas under one cleverly ambiguous banner.

For students of Greek history, Aristotle’s earlier chapters—no matter their limitations—continue to be indispensable. Modern historians must approach the Athenaion Politeia with caution, acknowledging its partisan overtones while still appreciating its unique contributions to our understanding of this pivotal chapter in Athenian history. After all, without Aristotle’s controversial testimony, our picture of the rise of the Thirty Tyrants—and the intrigues that led to their brief, bloody regime—would be far more fragmentary.