A 100-Day Spectacle to Open the Colosseum

After built, the Colosseum was inaugurated with an unprecedented 100 days of games and spectacles

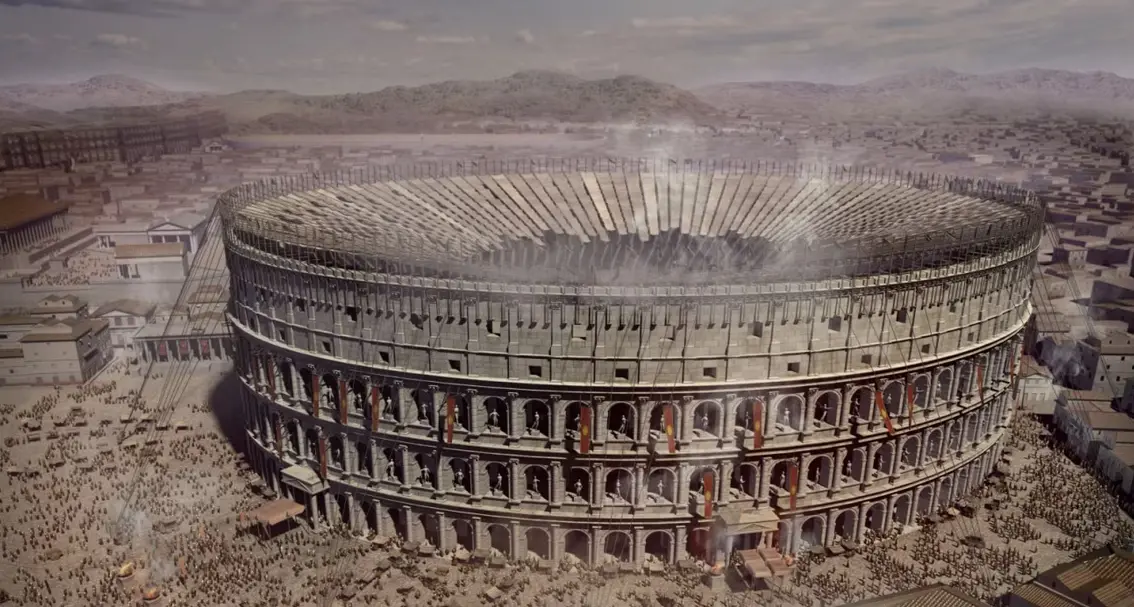

The Colosseum stands today as an iconic symbol of ancient Rome, a testament to the grandeur and engineering prowess of the Roman Empire. Completed during the reign of Emperor Titus in 80 or 81 CE, this magnificent amphitheater was inaugurated with an unprecedented 100 days of games and spectacles. If you were present in Rome during these inaugural games, you would have witnessed a dazzling array of entertainment that reflected the values, culture, and opulence of the 1st century CE.

The Building of the Colosseum

Unlike other entertainment arenas of the time, such as the Circus Maximus located on the city's outskirts, the Colosseum was centrally positioned in the heart of Rome. This prime location was made possible by the catastrophic Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, which devastated the area and cleared the way for new construction. Emperor Nero initially seized this space to erect his lavish palace, the Domus Aurea or “Golden House.” However, after Nero’s death and the tumultuous Year of the Four Emperors in 69 CE, Vespasian rose to power, establishing the Flavian Dynasty and reclaiming the land for public use.

Vespasian’s reign was marked by efforts to restore traditional Roman values and stabilize the empire. To solidify his legacy and gain favor with the populace, he pledged to use the spoils of war to build a new amphitheater that would provide the people with the much-desired “bread and circuses.” This grand structure, later known as the Colosseum, was a direct response to the people’s need for entertainment and a symbol of the Flavian commitment to Rome's grandeur.

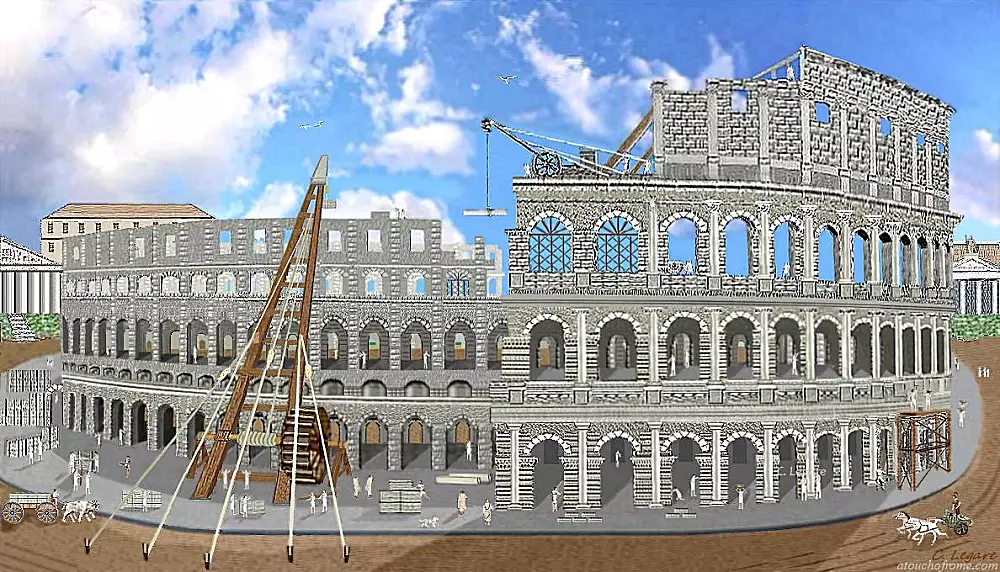

Coliseum 3D Animation Construction

The Flavian Dynasty and the Inauguration

Vespasian began his reign by showcasing his military prowess alongside his son and successor, Titus. Their joint triumph in Rome in 72 CE, celebrating the suppression of the Jewish revolt, was a prelude to the grand inauguration of the Colosseum. Vespasian’s decision to dismantle Nero’s Domus Aurea and repurpose the land for the amphitheater was a strategic move to present himself as a generous patron to the Roman people, reversing Nero’s excesses and restoring public spaces for communal enjoyment.

The amphitheater, initially known as the Amphitheatrum Caesarum, was only partially completed when Vespasian died in 79 CE. His son Titus swiftly took over the project, ensuring its completion by 80 or 81 CE. In addition to the Colosseum, Titus also constructed the Baths of Titus, further enhancing the architectural landscape of Rome. The inauguration of the Colosseum was a momentous event, marked by lavish games that would set the standard for Roman entertainment for centuries to come.

The Inaugural Games: An Overview

The inauguration of the Colosseum was not a mere ceremonial event but a grand spectacle that spanned 100 days, offering a variety of entertainments that captivated the Roman populace. These games were meticulously documented by contemporary sources, most notably by the poet Martial in his collection of epigrams known as the Liber de Spectaculis. Martial’s writings provide a vivid portrayal of the diverse and extravagant spectacles that took place, ranging from gladiatorial combats and exotic animal hunts to elaborate re-enactments of historical and mythological events.

Emperor Titus, keen on establishing his popularity and legitimacy, orchestrated these games to impress the citizens of Rome. The timing was impeccable, as Rome was recovering from another great fire in early 80 CE and the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, which had destroyed several Italian cities. The games served not only as entertainment but also as a means of uniting and uplifting the spirits of the Roman people during a period of rebuilding and recovery.

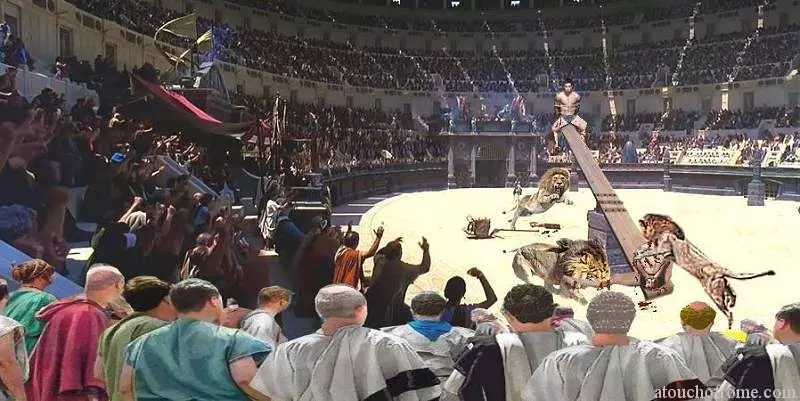

Scene in movie Quo Vadis, a colosseum full of viewer to watch animal battles and execution agaisn Chrtistians

Day at the Games: What to Expect

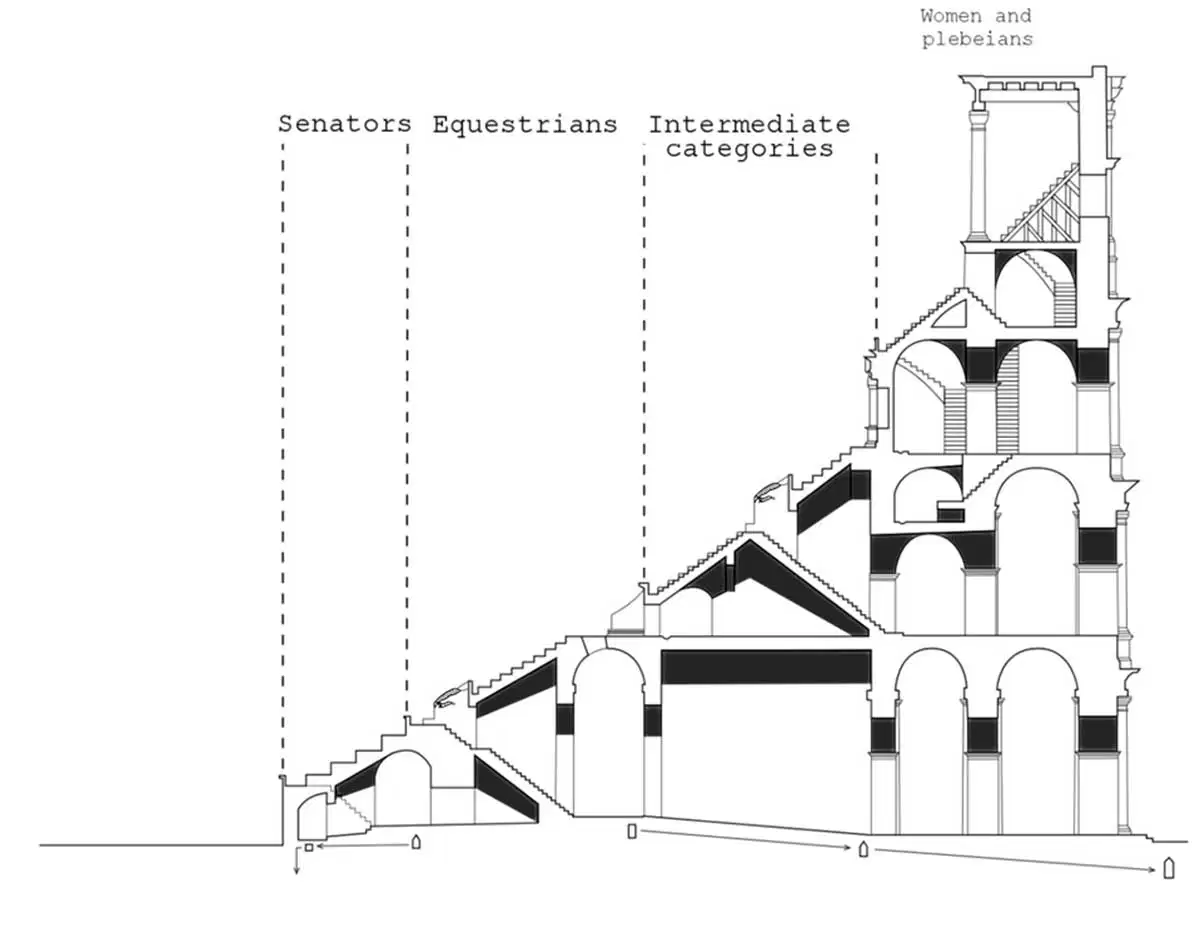

Attending the inaugural games at the Colosseum was a grand affair, though not accessible to everyone in Rome. The amphitheater could accommodate between 60,000 to 80,000 spectators, but with a population of over a million, securing a seat required luck or status. Tickets, made of wood, terracotta, or bronze, were distributed, often by lot, directing holders to specific entrances and seating areas. The seating was meticulously organized, with senators and important figures enjoying prime spots close to the action, while the common people were relegated to the upper tiers, offering a panoramic view but at a distance from the spectacle.

A day at the games was an all-day experience, starting in the morning and extending into the evening. The program was carefully structured: morning was reserved for animal spectacles, midday for executions, and the afternoon for gladiatorial combats or historical re-enactments. Regardless of the weather, the games continued, with sailors operating canopies to shield spectators from the sun or rain, ensuring that the entertainment was uninterrupted.

Food and refreshments were readily available, with vendors offering a variety of snacks such as chicken, shellfish, olives, nuts, and fruits like peaches, cherries, and grapes. Wine was also consumed, as evidenced by pot shards found in the sewers, and public water fountains provided hydration. While there were bathrooms, they were likely uncomfortable by the end of the day, much like modern stadium facilities.

Beyond the spectacle, attending the games offered the chance to receive the emperor’s generosity. Titus distributed goods like bread and made donatives—gifts given to the crowd. According to Cassius Dio, Titus threw wooden balls inscribed with specific gifts into the audience, which could be exchanged for prizes such as food, clothing, slaves, horses, cattle, gold, and silver. This display of generosity was a strategic move to endear himself to the populace and reinforce his image as a benevolent ruler.

Morning Entertainments: Animal Spectacles

The day’s entertainment began with thrilling animal spectacles, a staple of Roman games. Titus’s inaugural games featured an astounding 9,000 tame and wild animals, including lions, leopards, tigers, hares, pigs, bulls, bears, wild boars, rhinos, buffalo, and bison. These animals were imported from across the empire, showcasing the vast reach and resources of Rome.

Training and maintaining such a diverse array of animals required significant effort and expense. One of Martial’s epigrams recounts a dramatic scene where a tiger, under the control of its trainer, tore apart a lion, only to lick its master’s hand—a testament to the exotic and fierce nature of the spectacles. Another celebrated performer, Carpophorus, was renowned for his prowess in handling formidable beasts like bears and lions, earning fame through his skill and bravery in the arena.

A particularly memorable moment described by Martial involved an elephant bowing before the emperor, a display that symbolized the animal’s perceived recognition of Titus’s power and divinity. While likely trained to perform such acts, this spectacle underscored the emperor’s central role in the games, elevating his status and reinforcing his authority in the eyes of the spectators.

Midday Executions

As the sun reached its zenith, the games transitioned to more somber entertainments: executions. These events were typically conducted away from the emperor’s direct involvement, in line with traditional practices. Senators and other dignitaries would leave the arena during these proceedings, avoiding the bloodshed and brutality that executions entailed. This separation ensured that the emperor maintained an image of moral integrity and did not associate himself directly with the more violent aspects of the games.

Executions varied in form, ranging from crucifixions to brutal maulings by wild animals. Sometimes, these acts were dramatized through elaborate re-enactments of mythological stories. For instance, one spectacle reenacted the punishment of Prometheus, the Titan condemned to have his liver eaten daily by a carrion bird. Another depicted the tragic death of Orpheus, who was torn apart by women in Greek myth. These performances not only provided entertainment but also conveyed moral and cultural narratives, reinforcing societal values and the might of Rome.

Martial’s epigrams vividly describe these re-enactments, highlighting the dramatic and often gruesome nature of the executions. By bringing these myths to life, the games served as a medium for storytelling, embedding the grandeur and mythos of ancient tales into the fabric of Roman public life.

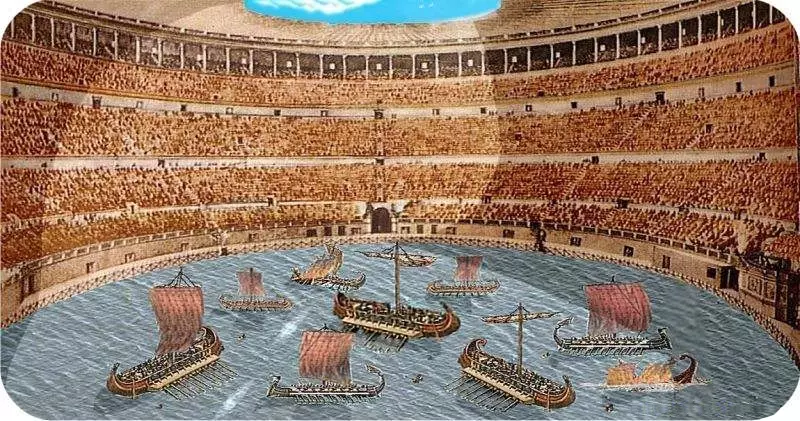

Naumachia Sea Battles

One of the most spectacular forms of entertainment at the Colosseum was the Naumachia, or naval battles. These elaborate reenactments of famous maritime conflicts were a favorite among Romans, offering a unique blend of theater and combat. Augustus had previously constructed an artificial lake for such spectacles, and the tradition continued under Titus’s rule.

Cassius Dio notes that Naumachia shows were held both at Augustus’s maritime arena and possibly within the Colosseum itself. Martial suggests that the stadium was flooded and drained on the same day, indicating that the Colosseum might have been equipped with the necessary infrastructure to host these water-based spectacles. These battles featured full-sized ships and engaged combatants, providing a realistic and immersive experience for the audience.

The Naumachia not only showcased Rome’s naval prowess but also served as a demonstration of the empire’s engineering capabilities. The ability to flood and drain the arena for these events was a marvel of Roman engineering, highlighting the ingenuity that allowed such grand spectacles to take place in the heart of the city.

Afternoon Gladiatorial Combats

The highlight of the day’s entertainment was undoubtedly the gladiatorial combats, a deeply ingrained aspect of Roman culture. These battles were the most popular events, drawing massive crowds eager to witness the skill, bravery, and ferocity of the gladiators. Trained in specialized schools located near the Colosseum, gladiators were often slaves or prisoners of war, though some volunteered for the glory and potential rewards.

Martial provides a detailed account of one such combat between veterans Verus and Priscus. Their fight was marked by an extraordinary display of equal skill and determination, resulting in a stalemate that defied the usual outcome of victor and vanquished. Instead of forcing the combatants to continue until one emerged as the sole winner, Titus honored their valor by declaring both gladiators as victors. Each was awarded a wooden sword, symbolizing their freedom—a rare and significant gesture that underscored Titus’s benevolence and the emperor’s desire to leave a lasting legacy of fairness and generosity.

This unprecedented decision not only captivated the audience but also reinforced the emperor’s reputation as a just and magnanimous ruler. By granting freedom to both gladiators, Titus set a precedent that elevated the gladiatorial combats from mere bloodsport to a celebrated display of honor and respect for bravery.

A tour of Colloseum today

Conclusion

The inaugural games of the Colosseum were a monumental event in ancient Rome, encapsulating the empire’s grandeur, cultural values, and the political acumen of the Flavian Dynasty. Over 100 days, the Colosseum became the epicenter of public entertainment, offering a diverse array of spectacles that appealed to all levels of Roman society. From the ferocious animal hunts and brutal executions to the awe-inspiring naval battles and heroic gladiatorial combats, these games were designed to impress, entertain, and unify the Roman people.

Emperor Titus’s careful orchestration of the games not only celebrated the completion of the Colosseum but also solidified his and his family’s legacy as benevolent and powerful rulers. The Colosseum’s inaugural games set the stage for centuries of Roman entertainment, leaving an indelible mark on history and ensuring that this magnificent amphitheater would remain a symbol of Rome’s enduring legacy.

Whether you imagine yourself as a senator enjoying the best seats or a commoner in the upper tiers cheering for your favorite gladiator, the 100 days of spectacles at the Colosseum offer a fascinating glimpse into the heart of ancient Rome’s social and cultural life. The grandeur and variety of the inaugural games highlight why the Colosseum remains one of the most celebrated and enduring monuments of the ancient world.